|

| JWikipedia - John Calvin: French Theologian and Reformer |

My Background in Calvinism

As I told one individual not long ago, my Christian background included being raised in a fundamental Baptist Church (GARB, General Assembly of Regular Baptist Churches) which later joined its church culture some fifty years later with the conservative evangelical movement. Its pastor/teacher has never been rivaled in my experience for his instruction, warm-hearted faith, and deep pastoral care for his beloved congregation.

I next attended an IFCA independent fundamental bible church during my university years. There I experienced wonderfully strong preaching by a hard-headed, warm-hearted converted Jew to Christianity in South Africa. And having ministered in Johannesburg came to America to preach. Here were warm, close days of Christian unity in bond and witness which fought against the liberalism of its day and yearned with the passion of Christ to be wholly worthy of their Savior God.

Having left university after three years of heavy mathematics and science I transferred to a (GARB-based) Baptist College, and later its Seminary to graduate with an Masters of Divinity (M.Div). I took a major in psychology (35 cr hrs?) and a strong minor in Bible (30 cr hrs?) to finish out my undergraduate study. During this time I had rejoined my home church and participated in many ministries from its fellowship. Mostly visitation, evangelism, and cold calling but also worship ministries, choir, and musical productions as well.

At marriage my wife and I could count five ministries we either conducted or participated in from children's ministries to high school to adult ministries of various kinds. I stayed with choir because of the excellent music director and we eventually left when several of the under-pastors refused further ministries without going through their year(s)-long indoctrination course. Here we left the church and moved to my wife's church, a former Reformed Church (RCA) turned Inter-denominational with stupendous oratory preaching in the fashion of Billy Sunday of old.

We had been married five years by then and when leaving my home church of many, many years to go to my wife's fellowship I found myself immersed within my first conservative evangelical church experience. In those days I had considered its ways and beliefs as liberal compared to my stricter background. But it was its atmosphere of healthy embrace to me and my wife which endeared us. By then I had craved an atmosphere free of judgmentalism of everyone and everything and yearned to minister in a more formal way. This I found in leading yet another set of youth ministries, this time in the college, career, and later, older singles level. It also included adult congregation assimilation ministries, worship ministries for a time, deaconing and other responsibilities. I even had several years of hosting a church-wide Christmas Eve Service through our college ministries and went so far as holding another church-wide Sedar Observation one Easter. The fellowship also saw my completion of seminary and two years later the birth of our first miracle child of two.

Twenty years of volunteer ministry came-and-went and through those formative years under a new pastor who had left the political conservative right movement to simply preach Jesus without any partisan portrayals. By then our church had successfully replanted several small area fellowships and began another one on the far side of town. After a month of operation we joined it by the pastor's urging to his congregation. Within two or three months of commencement the new church had far outstripped its facilities, its need for any fiscal help by our former church, and became the fastest growing church in America for a time. There we learned for the first time what Emergent Christianity meant (later to be known generally as Progressive Christianity). It sought Jesus with a passion to the exclusion and refusal of conservative evangelical doctrine which held it back by its rules and exclusions. Which also got our new fellowship into trouble with area evangelical churches around it and nationwide. Still my wife and I stayed through the ups and downs and after twenty years of listening and wrestling with post-evangelical emergent approach and doctrine our children had grown up, had been out of the home for ten years, and my wife wanted to move to another part of town. It was time to begin anew. We had reached and gone beyond middle age. The years of youth were now past.

Currently, we fellowship with several area evangelical assemblies each dealing with the after effects of Trumpian Christianity gone terribly wrong. The evangelicalism I once knew has now died in its own cesspools of exclusion and self-indictments and like many other wrecked faiths have left many Christians homeless and disillusioned about what to do. Whether to double down or move on? Having sensed this spiritual degradation some years earlier I had begun re-examining my own church and bible training backgrounds. It also meant that for awhile I would enter into a very dark time of wilderness sojourney. During that time of darkness my church doctrine would switch from its failed Cal-minian roots back to its original Arminian roots which I knew nothing of, but in later years of study would come to embrace having seen the end of Calvinism into its degenerate forms of neo-Calvinism.

And so this I have done. Through its course it would expand towards Open and Relational Theology as Arminianism's natural contemporary predecessor. To this direction I have been adding Process Theology as the greater, more expansive Christian route to follow in these days of church cynicism and degradation of its faith. For the novice, what some call Progressive Christianity (birthed from its own roots of Emergent Christianity) is an expanded form of post-evangelicalism in its healthier forms of faith and worship. Now Process Theology may have its roots in Emergent and Progressive Christianity as a post-evangelical movement but is more formally defined as coming from the end-of-life work of Alfred North Whitehead having retired from mathematics and burdened to write down what he called a Philosophy of Organism. This later has become known as Process Philosophy. The Theology part of it comes from Whitehead's own Christian faith. So at once Whitehead's Philosophy of Organism is both philosophical and theological. This would not be dissimilar to what John Calvin did when writing his Institutes nor what Jakob Arminius' students did with Jakob's teachings on theology. In history, such literate visionaries look into the future to envisage what they believe will bring aide and comfort to the masses. So too Thomas Paine, John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Marx and Engels, and on and on. All well intentioned until it isn't anymore.

Per its roots, Calvinism is a faith which cites Scripture upholding to a perfect, high holy God whose rules over creation and all those who are worthy, or not worthy, of His love, and therefore must be condemned under His wrath to death and damnation. However, Messiah Christ is the One who comes to save mankind to prevent this tragedy from happening. That, in a nutshell is Calvinism and Evangelicalism wrapped up into one. In contrast, Process Theology returns to God's love as the center for all things, and the Christ of the Cross, as I had once learned through my earlier worship and study experiences. It is also this latter direction I wish to pursue by throwing out all the old rules I had learned under profane Calvinism by either modifying them or starting over all together. Hence, the past ten years have been an intense period of deconstructing and reconstructing my faith newly rebuilt upon the epistemic faith foundations of Christian uncertainty and doubt (but not fear!). I have found it extremely healthy for my spiritual walk with God granting days of wonderment and amazement how deep and wide the love of God is everywhere about us. It flows like a massive river we don't even realize is there!

Below is a condensed summary of several important creeds and confessions of Calvinism's Protestant roots beginning back in the 1500s and how it was responded to by then converting Catholic assemblies during the next 100 years through the 1600s. From its birth, Calvinism has been deeply directional for many denominational forms of Protestantism as faith assemblies were leaving behind the Catholic Church with its scholastic teachings. It is also where many evangelical churches have centered their faith today within the maze of secular Christian ideology and practice. For a fuller history of the Protestant church read Latourette's books to help explain and provide insight. I might also suggest for those Catholic readers here that Thomism and Franscican orders seem relevant for today. For myself, anything that Pope Francis says and does is highly helpful and relevant (mostly, but not always aka the church's position of LGBTQ lately). I also would remind everyone that Process Theology, or Process Christianity, is very fluid and easy to adapt into any Christian faith or sect. You will also find many of its elements in world religions which may also then be instructive to the Islamic and Buddhist faiths to mention a few.

R.E. SlaterApril 20, 2021

RELATED REFERENCES

FOUNDATIONS OF THE FAITH

An intelligent member of the Catholic middle-class, John Calvin (1509-1564) had the family connections to place him in good schools. He left home in Noyon, France, in 1523, and traveled south to Paris to study law on a church scholarship. There he was exposed to theological conservatism, humanism, and a movement calling for the reformation of the church.

Young Calvin, his name Latinized to Ioannis Calvinus, completed his studies and settled in Paris. He experienced what he described as “a sudden conversion” and joined reform-minded activists who were taking stronger and more public stands on church reform. When his friend Nicholas Cop was installed as rector at the University of Paris in 1533, Cop advocated for church reforms in his inaugural address. Some believed Calvin authored Cop’s controversial remarks, which showed affinities with Desiderius Erasmus and Martin Luther, and Calvin was forced to flee Paris.

The twenty-four year old Calvin relocated to Reformation-minded Basel, where in 1536, he wrote his six-chapter distillation of evangelical faith, published in Latin: Christianae religionis instituto, or Institutes of the Christian Religion. This treatise was systematic and clear. It derived much of its form and substance from Luther’s Kleiner Katechismus (1529) and addressed law, the Decalogue, the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the sacraments, and Church government.

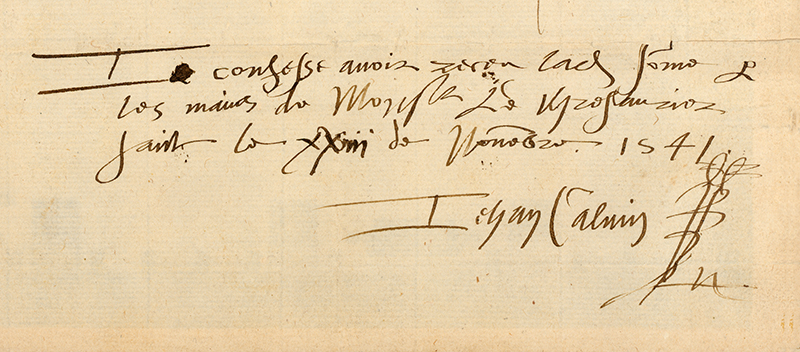

Passing through Geneva later that year, he was persuaded to stay and assist in organizing the Reformation in that city. However, on Easter Day 1538, Calvin publicly defied the city council’s instructions to conform to the Zwinglian religious practices of Berne and was ordered to leave. After serving as pastor to the French congregation in Strasbourg for three years, Calvin accepted an invitation to return to Geneva. In 1541, he began fourteen years of work to establish a theocratic regime in the city, and his Ecclesiastical Ordinances were adopted by the city council in November 1541. These ordinances distinguished four ministries within the church: pastors, doctors, elders, and deacons. Other reforming measures included introducing vernacular catechisms and liturgy.

Over time, John Calvin expanded on and refined his thinking in the Institutes. Responding to the considerable interest in the work and the controversy it generated, he issued a much expanded eighty-chapter version. The text became the most important theological text of the Reformation. The 1559 Latin edition was widely circulated in various forms, becoming the theological source document of Protestantism. The Institutes is hailed as the cornerstone of Calvinist theology.

Calvin’s theology proved to be the driving force of the Reformation, particularly in Western Germany, France, the Netherlands, England, and Scotland. It was from Calvin that John Knox gained the knowledge of Reformed theology and polity that he used as the basis for founding the Presbyterian denomination.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Three Forms of Unity

The Three Forms of Unity is a collective name for the Belgic Confession, the Canons of Dort, and the Heidelberg Catechism, which reflect the doctrinal concerns of continental Calvinism and are accepted as official statements of doctrine by many of the Reformed churches.

History

From 1618 to 1619 the Dutch government, on behalf of the Dutch Reformed Church, called and convened the Synod of Dort. Dutch delegates, along with twenty-seven Reformed representatives from eight other countries, met at this Synod of Dort, where they collectively summarized their views in what was called the "Canons of Dort".[1]

This same Synod then added these Canons to two other documents, both of which were in common use by the Dutch Church at the time: the Heidelberg Catechism (1563) and the Belgic Confession (1561).[1]

In so doing, the Synod sought:

- to formalize their understanding of the biblical teachings on the Trinity, the incarnation, predestination, justification, and the church;

- to allow members to gather together in unity around fundamental, shared beliefs;

- to relegate certain non-essential ideas (political positions, educational platforms, etc.) to a lower status to prevent the churches from needlessly splitting — the forms also provide a basis upon which ecumenical efforts can proceed based on whether a body accepts the essentials laid out in these forms

The different documents each serve different purposes.

- The Heidelberg Catechism is written in a question-and-answer format to help explain biblical teaching to children and those new to the faith.

- The Belgic Confession explains various biblical teachings.

- The Canons of Dort are a series of technical responses to specific theological controversies raised by the Dutch Remonstrants (see History of the Calvinist-Arminian debate).

References

- ^ a b FRC: Canons of Dort – Historical Background Archived 30 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Text and description of the Three Forms from Philip Schaff's Creeds of the Evangelical Protestant Churches at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library:

- Belgic Confession (in the original French with a translation into English)

- Heidelberg Catechism (in the original German with a translation into English)

- Canons of Dort (in the original Latin with a translation into English)

- Audio Recordings of the Three Forms of Unity in MP3 format

Belgic Confession

The Confession of Faith, popularly known as the Belgic Confession, is a doctrinal standard document to which many of the Reformed churches subscribe. The Confession forms part of the Three Forms of Unity of the Reformed Church,[1] which are still the official subordinate standards of the Dutch Reformed Church.[2][3] The confession's chief author was Guido de Brès, a preacher of the Reformed churches of the Netherlands, who died a martyr to the faith in 1567, during the Dutch Reformation.[4] De Brès first wrote the Belgic Confession in 1559.[5]

Terminology

The name Belgic Confession follows the seventeenth-century Latin designation Confessio Belgica. Belgica referred to the whole of the Low Countries, both north and south, which today is divided into the Netherlands and Belgium.

Authorship and revisions

De Brès was a Presbyterian and a Calvinist,[6] and the initial text he prepared was influenced by the Gallic Confession. De Brès showed it in draft to others, including Hadrian à Saravia, Herman Moded, and Godfried van Wingen (Wingius). It was revised by Franciscus Junius, who abridged the sixteenth article and sent a copy to Geneva and other churches for approval; and was presented to Philip II of Spain in 1562, in the hope of securing toleration for his Protestant subjects in the Low Countries.[7] In 1566, the text of this confession was revised at a synod held at Antwerp. It was adopted by national synods held during the last three decades of the sixteenth century.[8]

The Belgic Confession became the basis of a counter to the Arminian controversy that arose in the following century and Arminius opposed the notion that it could be used against his theology.[9] Furthermore, contrary to popular thought and allegations to the contrary, Arminius maintained his affirmation of the Belgic Confession until his death in October 1609.[10][11] The text was revised again at the Synod of Dort in 1618-19, was included in the Canons of Dort (1618–19), and adopted as one of the doctrinal standards to which all office-bearers and members of the Reformed churches were required to subscribe. This revision was drafted in the French language (1618–19).

Composition

The Belgic Confession consists of 37 articles which deal with the doctrines of God (1-2, 8-13), Scripture (3-7), humanity (14), sin (15), Christ (18-21), salvation (16-17, 22-26), the Church (27-36), and the end times (37).

Editions and translations

The first French edition is extant in four printings, two from 1561 and two from 1562.[12] The Synod of Antwerp of September 1580 ordered a copy of the revised text of Junius to be made for its archives, to be signed by every new minister; this manuscript has always been regarded in the Belgic churches as the authentic document. The first Latin translation was made from Junius's text by Theodore Beza, or under his direction, for the Harmonia Confessionum (Geneva, 1581), and passed into the first edition of the Corpus et Syntagma Confessionum (Geneva, 1612). A second Latin translation was prepared by Festus Hommius for the Synod of Dort, 1618, revised and approved 1619; and from it was made the English translation in use in the Reformed (Dutch) Church in America. It appeared in Greek 1623, 1653, and 1660, at Utrecht.[7]

References

- ^ Horton 2011, p. 1002

- ^ Cochrane 2003, p. 187

- ^ Latourette & Winter 1975, p. 764

- ^ Cochrane 2003, p. 185

- ^ Bangs, Carl (1998). Arminius: A Study in the Dutch Reformation. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers. pp. 100–01. ISBN 1-57910-150-X. OCLC 43399532.

- ^ Latourette & Winter 1975, p. 763

- ^ a b Jackson 1952, p. 32

- ^ Bangs 1961, p. 159

- ^ Bangs 1997, p. 119

- ^ Bangs, Carl (1973). "Arminius as a Reformed Theologian". In Bratt, John H. (ed.). The heritage of John Calvin : Heritage Hall lectures, 1960-70. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. pp. 216–17. ISBN 0-8028-3425-6. OCLC 623481.

- ^ Pinson, J. Matthew (2015). "Jacobus Arminius: Reformed and Always Reforming". Arminian and Baptist: Explorations in a Theological Tradition. Nashville, Tenn.: Randall House. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0-89265-696-7. OCLC 919475036.

- ^ Gootjes 2007, Chapter 1

Sources

- Bangs, Carl (June 1961), "Arminius and the Reformation", Church History, Cambridge University Press, 30 (2): 155–170, doi:10.2307/3161969, ISSN 0009-6407, JSTOR 3161969

- Bangs, Carl (March 1997), "Review: God, Creation, and Providence in the Thought of Jacob Arminius", Church History, Cambridge University Press, 66 (1): 118–120, doi:10.2307/3169661, ISSN 0009-6407, JSTOR 3169661

- Cochrane, Arthur (2003), Reformed Confessions of the Sixteenth Century, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0-664-22694-7, retrieved 2013-02-13

- Gootjes, Nicolaas (1 November 2007), The Belgic Confession, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, ISBN 978-0-8010-3235-6, retrieved 2013-02-13

- Horton, Michael (21 December 2011), The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-40918-2, retrieved 2013-02-13

- Jackson, Samuel, ed. (1952), "Belgic Confession", The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia, II, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, retrieved 2013-02-13

- Latourette, Kenneth; Winter, Ralph (1975), A History of Christianity, 2, Peabody: Prince Press, ISBN 978-1-56563-329-2, retrieved 2013-02-13

Canons of Dort

The Canons of Dort, or Canons of Dordrecht, formally titled The Decision of the Synod of Dort on the Five Main Points of Doctrine in Dispute in the Netherlands, is the judgment of the National Synod held in the Dutch city of Dordrecht in 1618–19.[1] At the time, Dordrecht was often referred to in English as Dort or Dordt.

Today the Canons of Dort form part of the Three Forms of Unity, one of the confessional standards of many of the Reformed churches around the world, including the Netherlands, South Africa, Australia, and North America. Their continued use as a standard still forms an unbridgable problem preventing close cooperation between the followers of Jacob Arminius, the Remonstrants, and Dutch Reformed Churches.

These canons are in actuality a judicial decision on the doctrinal points in dispute from the Arminian controversy of that day. Following the death of Arminius (1560–1609), his followers set forth a Remonstrance (published in 1610) in five articles formulating their points of departure from the stricter Calvinism of the Belgic Confession. The canons are the judgment of the Synod against this Remonstrance.[2] Regardless, Arminian theology later received official acceptance by the State and has since continued in various forms within Protestantism, especially within the Methodist churches.[3]

The canons were not intended to be a comprehensive explanation of Reformed doctrine, but only an exposition on the five points of doctrine in dispute.[4] The five points of Calvinism, remembered by the mnemonic TULIP[a] and popularized by a 1963 booklet,[5] are popularly said to summarize the Canons of Dort.[6] However, there is no historical relationship between them, and some scholars argue that their language distorts the meaning of the canons.[7]

Notes

- ^ Total depravity, unconditional election, limited atonement, irresistible grace, and perseverance of the saints.

References

- ^ Horton, Michael (2011). The Christian Faith. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 562. ISBN 0310286042.

- ^ Peterson, Robert; Williams, Michael (2004), Why I am not an Arminian, Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, p. 124, ISBN 0830832483

- ^ Olson, Roger E. (20 August 2009). Arminian Theology. InterVarsity Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780830874439.

Arminian theology was at first suppressed in the United Provinces (known today as the Netherlands) but caught on there later and spread to England and the American colonies, largely through the influence of John Wesley and the Methodists.These Canons of Dordt (or Dort) made by the Dutch Reformed Churches are still used in many reformed churches today.

- ^ "Canons of Dort". 4 June 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Kenneth J. (2008). "The Points of Calvinism: Retrospect and Prospect" (PDF). Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology. 26 (2): 189–193.

- ^

- R. C. Sproul (1997), What is Reformed Theology?, Grand Rapids: Baker Books, pp. 27–28.

- Chapter 3 of: Stewart, Kenneth J. (2011). Ten Myths about Calvinism. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press.

- ^ Muller, Richard A. (2012). Calvin and the Reformed Tradition (Ebook ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. pp. 50–51.

Further reading

- But for the Grace of God by Cornelis P. Venema

- The Golden Chain of Salvation by John Bouwers

- Unspeakable Comfort by Peter Feenstra

- The Voice of Our Fathers by Homer Hoeksema

- The Reformed Doctrine of Predestination by Lorraine Boettner

- The Synod of Dordt by Thomas Scott

- The Canons of Dordt by Henry Peterson

- The Five Points of Calvinism by David Steele and Curtis Thomas

- The Works of John Owen, Vol. 10

- TULIP by William Jay Hornbeck II

External links

Heidelberg Catechism

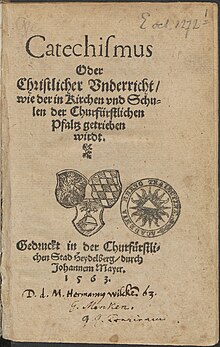

The Heidelberg Catechism (1563), one of the Three Forms of Unity, is a Protestant confessional document taking the form of a series of questions and answers, for use in teaching Reformed Christian doctrine. It was published in 1563 in Heidelberg, present-day Germany. Its original title translates to Catechism, or Christian Instruction, according to the Usages of the Churches and Schools of the Electoral Palatinate. Commissioned by the prince-elector of the Electoral Palatinate, it is sometimes referred to as the "Palatinate Catechism." It has been translated into many languages and is regarded as one of the most influential of the Reformed catechisms.

History

Elector Frederick III, sovereign of the Electoral Palatinate from 1559 to 1576, commissioned the composition of a new Catechism for his territory. While the catechism's introduction credits the "entire theological faculty here" (at the University of Heidelberg) and "all the superintendents and prominent servants of the church"[1] for the composition of the catechism, Zacharius Ursinus (1534–83) is commonly regarded as the catechism's principal author. Caspar Olevianus (1536–87) was formerly asserted as a co-author of the document, though this theory has been largely discarded by modern scholarship.[2][3] Johann Sylvan, Adam Neuser, Johannes Willing, Thomas Erastus, Michael Diller, Johannes Brunner, Tilemann Mumius, Petrus Macheropoeus, Johannes Eisenmenger, Immanuel Tremellius and Pierre Boquin are all likely to have contributed to the Catechism in some way.[4] Frederick himself wrote the preface to the Catechism[5] and closely oversaw its composition and publication.

Frederick, who was officially Lutheran but had strong Reformed leanings, wanted to even out the religious situation of his highly Lutheran territory within the primarily Catholic Holy Roman Empire. The Council of Trent had just finished its work with its conclusions and decrees against the Protestant faiths, and the Peace of Augsburg had only granted toleration for Lutheranism within the empire where the ruler was Lutheran. One of the aims of the catechism was to counteract the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church as well as Anabaptists and "strict" Gnesio-Lutherans like Tilemann Heshusius (recently elevated to general superintendent of the university)[6] and Matthias Flacius, who were resisting Frederick's Reformed influences, particularly on the matter of the Eucharist.

The Catechism-based each of its statements on biblical source texts (although some may call them "proof-texts" which can have a negative connotation), but the "strict" Lutherans continued to attack it, the assault being still led by Heshusius and Flacius. Frederick himself defended it at the 1566 Diet of Augsburg as based in scripture rather than based in reformed theology when he was called to answer to charges, brought by Maximilian II, of violating the Peace of Augsburg. Afterwards, the catechism quickly became widely accepted.[6]

The Catechism is divided into fifty-two sections, called "Lord's Days," which were designed to be taught on each of the 52 Sundays of the year. A synod in Heidelberg approved the catechism in 1563. In the Netherlands, the Catechism was approved by the Synods of Wesel (1568), Emden (1571), Dort (1578), the Hague (1586), as well as the great Synod of Dort of 1618–19, which adopted it as one of the Three Forms of Unity, together with the Belgic Confession and the Canons of Dort.[7] Elders and deacons were required to subscribe and adhere to it, and ministers were required to preach on a section of the Catechism each Sunday so as to increase the often poor theological knowledge of the church members.[7] In many Reformed denominations originating from the Netherlands, this practice is still continued.

Structure

In its current form, the Heidelberg Catechism consists of 129 questions and answers. These are divided into three main parts:

I. The Misery of Man

This part consists of the Lord's Day 2, 3, and 4. It discusses:

II. The Redemption (or Deliverance) of Man

This part consists of Lord's Day 5 through to Lord's Day 31. It discusses:

- The need for a Redeemer

- The importance of faith, the content of which is explained by an exposition of the 12 Articles of the Christian faith, known as the Apostles' Creed. The discussion of these articles is further divided into sections on:

- God the Father and our creation (Lord's Days 9–10)

- God the Son and our salvation (Lord's Days 11–19)

- God the Holy Spirit and our sanctification (Lord's Days 20–22)

- Justification

- The Sacraments of Baptism and the Lord's Supper

- And the keys of the kingdom of heaven The Preaching of the Gospel and Church Discipline

III. The Gratitude Due from Man (for such a deliverance)

This part consists of the Lord's Day 32 through to Lord's Day 52. It discusses:

- Conversion (Lord's Days 32–33)

- The Ten Commandments (Lord's Days 34–44)

- The Lord's prayer (Lord's Days 45–52)

Lord's Day 1

The first Lord's Day should be read as a summary of the catechism as a whole. As such, it illustrates the character of this work, which is devotional as well as dogmatic or doctrinal. The first Question and Answer reads:

The answer is:

Lord's Day 30

The Catechism is most notoriously and explicitly anti-Catholic in the additions made in its second and third editions to Lord's Day 30 concerning "the popish mass," which is condemned as an "accursed idolatry."

Following the War of Palatine Succession Heidelberg and the Palatinate were again in an unstable political situation with sectarian battle lines.[8] In 1719 an edition of the Catechism was published in the Palatinate that included Lord's Day 30. The Catholic reaction was so strong, the Catechism was banned by Charles III Philip, Elector Palatine. This provoked a reaction from Reformed countries, leading to a reversal of the ban.[9]

In some Reformed denominations Q&A 80, the first of Lord's Day 30, have been removed, bracketed, and/or noted as not part of the original Catechism.[10]

Use in various denominations and traditions

The influence of the Catechism extended to the Westminster Assembly of Divines who, in part, used it as the basis for their Shorter Catechism.[11]

The Heidelberg Catechism is one of the three Reformed confessions that form the doctrinal basis of the original Reformed church in The Netherlands, and is recognized as such also by the Dutch Reformed churches that originated from that church during and since the 19th century.

Several Protestant denominations in North America presently honor the Catechism officially: the Presbyterian Church in America, ECO (A Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians), the Christian Reformed Church, the United Reformed Churches, the Presbyterian Church (USA), the Reformed Church in America, the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches, the United Church of Christ (a successor to the German Reformed churches), the Reformed Church in the United States (also of German Reformed heritage),the Evangelical Association of Reformed and Congregational Christian Churches,[12] the Free Reformed Churches of North America, the Heritage Reformed Congregations, the Canadian and American Reformed Churches, Protestant Reformed Churches, and several other Reformed churches of Dutch origin around the world. Likewise, the Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church lists it as an influence on United Methodism.

A revision of the catechism was prepared by the Baptist minister, Hercules Collins. Published in 1680, under the title 'An Orthodox Catechism', it was identical in content to the Heidelberg catechism, with exception to questions regarding baptism, where adult immersion was defended against infant baptism and the other modes of affusion and aspersion.

References

- ^ Emil Sehling, ed., Die evangelischen Kirchenordnungen des XVI. Jahrhunderts, Band 14, Kurpfalz (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1969), 343: "Und demnach mit rhat und zuthun unserer gantzen theologischen facultet allhie, auch allen superintendenten und fürnemsten kirchendienern einen summarischen underricht oder catechismum unserer christlichen religion auß dem wort Gottes beides, in deutscher und lateinisher sprach, verfassen und stellen lassen, damit fürbaß nicht allein die jugendt in kirchen und schulen in solcher christlicher lehre gottseliglichen underwiesen und darzu einhelliglichen angehalten, sonder auch die prediger und schulmeister selbs ein gewisse und bestendige form und maß haben mögen, wie sie sich in underweisung der jugendt verhalten sollen und nicht ires gefallens tegliche enderungen fürnemen oder widerwertige lehre einfüren."

- ^ Lyle Bierma, "The Purpose and Authorship of the Heidelberg Catechism," in An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism: Sources, History, and Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 67.

- ^ Goeters, J.F. Gerhard (2006), "Zur Geschichte des Katechismus", Heidelberger Katechismus: Revidierte Ausgabe 1997 (3rd ed.), Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, p. 89.

- ^ "History", Heidelberg catechism.

- ^ "Preface" (PDF), Heidelberg catechism, Amazon.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 211.

- ^ a b "Historical Background", Heidelberg Catechism, FRC, archived from the original on 2008-05-12, retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Heidelberg#Modern history.

- ^ Thompson, Andrew C. (2006). Britain, Hanover and the Protestant Interest, 1688-1756. ISBN 9781843832416.

- ^ "CRC Releases Final Report on Catholic Eucharist". Christian Reformed Church in North America. 25 February 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ "Historic Resource Library". Evangelical Association of Reformed and Congregational Christian Churches. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

Further reading

- Bierma, Lyle D. (2005). Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism: Sources, History, and Theology. ISBN 978-0-80103117-5.

- Ernst-Habib, Margit (2013). But Why Are You Called a Christian? An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism. Goettingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-352558041-7.

External links

- Heidelberg Catechism (modern English translation): From the Reformed Church in the United States

- Heidelberg Curriculum for Families (text and audio)

- Audio Recording of the Heidelberg Catechism (mp3)

- Heidelberg-Catechism.com

No comments:

Post a Comment