|

| The Process of Being & Becoming |

Did Kant create an inseparable gulf between the subjective (self) and the objective (science) so that the former is devoid of reality and the latter of value?

Question: MN

I am as far as can be from a trained philosopher but it seems to me that Kant is as much a hinge, a place where we went wrong, as Descartes is. Is that right? My understanding is that Kant “solved”, or put to sleep, the argument between subjective and objective realms of knowledge by proclaiming that they were by nature separate and incommensurable. Then, over time, because of the much greater efficacy and “power” in the observable world of the objective, the subjective kind of withered away, leaving what we have today; a secular world devoid of value, and a religious world devoid of reality. Do I have that at all right? I am just trying to remind myself of why this all matters, as I am a bit bogged down. Thx

Response: Jay McDaniel

What Kant set in motion was a turn to the subject as arbiter of all knowledge, because we can't know reality in itself; we can only know what is necessarily filtered through the categories in our minds. This gave rise later to an emphasis on subjective, first-person experience, as in existentialism, and human language, as in linguistic philosophies. Meanwhile, Kant notwithstanding, science made great strides in understanding what scientists believed to be an objective world, [one] independent of human projection. A twofold divide was [thus] created: humanities, dealing with subjective human experience, and the sciences, dealing with the objective world.

Whitehead seeks to overcome this [Kantian] dualism in several ways, one of which is to suggest that the very building blocks of the objective world are, in fact, moments of subjective experience. He formulates this in terms of what he calls the reformed subjectivist principle. Additionally, with his notion of experience in the mode of causal efficacy, he proposes that the objective world even apart from our mental categories finds its way into our own experience. He believes that this mode of experience was neglected by many philosophers, and that it provides a bridge between an objective (past actual world) and the immediacy of subjective experience, as enjoyed by humans and other animals and, for that matter, the energy-events with the depths of atoms. All occasions of experience, not just human occasions, begin with experience in the mode of causal efficacy, thinks Whitehead. In human life this experience is felt, among other ways, in what he calls the "with-ness of the body."

* * * * * * * * * * * *

|

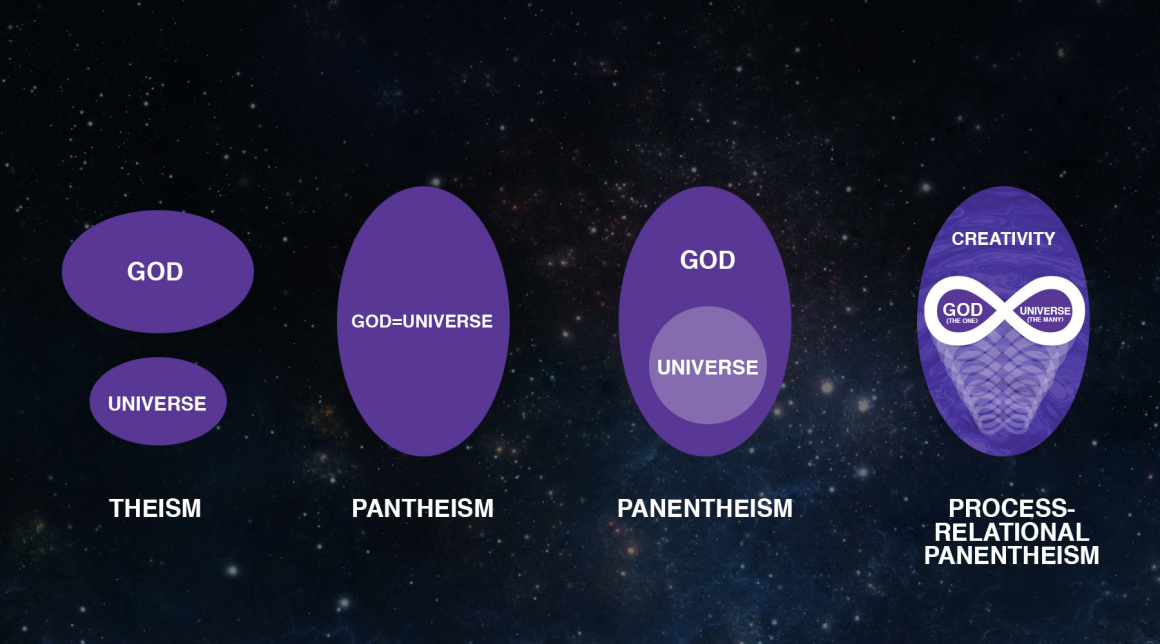

| Process-Relational Panentheism Diagram |

How is God the Ultimate in Whiteheadian Thought?

Question: R.E. Slater

I finally completed Session 2 with Dr. Cobb. His last 10 minutes of so of discussion left me with a lot of questions. Is there something he might have written - an article or two - which might speak to what he was trying to express in a clearer way? I could pick out elements of his thought but it seemed a bit scrambled on a topic he had thought about for a long time. Especially on the idea of God as Ultimate or non-Ultimate vs Platonic thought and modern philosophy. Thanks.

Response: Jay McDaniel

Here's my take. If you ask the question: "Is there a thing or an activity of which all actual entities are expressions in their self-creativity and in the immediacy of the moment which can be manifested in the transition from one moment to the next?" Whitehead's answer is Creativity, not God. Understood in this sense Creativity is neither good nor evil; it can unfold in either way. It is the ultimate 'matter' of which all things, even God, are expressions. It is the ultimate reality.

And if you ask: "And is there a primordial manifestation of this Creativity which has preferences, which is on the side of life's well-being, and which shares in the joys and sufferings of all?" Whitehead's answer is God, understood as the primordial expression of Creativity.

Likewise, the primordial nature of God contains all the pure potentialities which can be actualized by the world: that is, eternal objects. Thus God is cosmic mind of sorts (an ultimate intelligence or wisdom) as well as a compassionate friend of the universe (a deep listening, the consequent nature). God is the ultimate actuality.

This is how I understand Whitehead and also John's view, developed in dialogue with Buddhism many years ago, that there are two ultimates: the ultimate reality of Creativity and the ultimate actuality of God. The idea is helpful because it opens us up to the possibility that different religious traditions may be attuned to different ultimates, all of which are 'real' in their way.

To this list we might add still more: e.g. the present moment of experience (Zen) and the sheer interconnectedness of all things (Chinese philosophy.) The word "ultimate" names different realities relative to the question being asked. Thus the idea of a single and exclusive "ultimate" is abandoned.

Response: R.E. Slater

Thank you Jay. I need to digest this a bit more but its direction helps me better understand how Whitehead was approaching the subject of the Ultimate. In relational terms, God shares, or creates, from himself a creation like himself... one that is relational, creative, self-becoming, etc. He allows agency to the creative process without determinative superintendency over it. God then is both the ultimate actuality as will as the eventuating causal expression of creativity et al as He fellowships, communes, and journeys with creation. I'm discovering the differences in Whitehead to philosophical and theological thought can be a lot to digest.

One more thing to say, Russ. In Whitehead, God does not create the self-creativity of actual entiries. In the immediacy of the moment actual entities create in themselves a response to all the data they are given from the past actual world and God’s initial aims. This self-creativity is not reducible to God’s creativity or to the influences from the past. In this sense it is ultimate in its way. Even in the absence of God, it would be real. God works with this self-creativity but does NOT create it. This is one reason Whitehead names creativity as the ultimate reality. Even God has this capacity for self-creativity, but not God alone. God is ultimate in in a different way: as a lure for heightened creativity and a companion to all its expressions. It is God, not creativity. In whom monotheists plays their trust. This faith and awakening to creativity (as in some forms of Buddhist enlightenment and Hindu mysticism) are different, but both valid and potentially complementary. At least so it seems to me. Sorry to be so wordy.

Follow-up Response: R.E. Slater

Thank you Jay. I was thinking this but you helped fix the idea for me more concretely. That God is both the initial expression of creativity as He Himself is creative. Moreover, that creational creativity is an expression of God's creativity but without presidence over creational creativity in accordance with creational freewill agency. And finally, that both God and creation may everlastingly, to use John Cobb's term, create new creativities which have yet to be formed. This then would be the idea of "becoming" or "concrescence" of the organism or process-based union between God and creation.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Process Theology re Ontology, Culpability & Theodicy

Question: TB

Keep bringing that goodness, Jay! This is such a helpful distinction for those [newbies] who are orienting to Whitehead. I've got some questions I'd hold out before you in the framing you are laying out that differentiates God and creativity that come from Christian contemplative streams (although it crosses many contemplative traditions).

First, a preface, then a few questions. If creativity is neither good nor evil, and needs God (principle of concretion) to create an actual world and to maintain a full openness for that system to function with true freedom, the possibility for evil must be a real possibility, yes? Some contemplatives will claim that there is nothing real but love (I think of Finley and the CAC living school here, as well as Eckhart Tolle and others in saying that "nothing real can be threatened and nothing unreal exists"). And yet, in our subjective experience of the world, evil, trauma, and suffering do become actualized in the world -- thus making it feel (as in a felt sense of the Whiteheadian metaphysic) that they do indeed "exist" in that they have become "actualized" at the very least as an emotive quality that is produced by an actual body.

I've had a hard time relegating actual suffering as merely a product of one's emotions (which are to be detached from in both the Christian and Buddhist contemplative streams in order to gain peace), or to in any way to make a metaphysical claim like the complex embodied or emotional experiences of personally ordered societies that include experiences of evil, trauma, and suffering are not "real" or "actual" in any way. For instance, Odin and Whitehead will say something like, "the suffering attains its end in the sense of peace — the infinity of God in the infinite suffering. this is only achieved through a psychical distancing, detachment, or disinterested contemplation — of transcending the ego in order to connect to the transcendental ground of peace in the midst of experiences of suffering."

I know that Whitehead says that, ultimately, evil is only remembered as 'fact' and not value, but in the framing you laid out initially here, it sounds like God, as the primordial expression of creativity, contains within the divine mind even the pure potentials for evil, although clearly luring toward beauty. so, here are a few questions:

- Is evil an eternal object?

- If so, how could it be that God, in holding out pure potentials for a becoming world could contain within the divine mind potentials for evil and still be called 'good' in any sense of the word? Are humans who actualize "evil" thus following a lure of creativity rather than God? Or is there another solution?

- Are human emotions real or actual in any metaphysical sense?

- And lastly, perhaps a more pedagogical question...how is one to move through their human journey with its emotional and embodied events of suffering into a place of peace? Is it by detachment or psychical distancing? Or is there some other integration of the reality of "actual" or "real" suffering into one's perspective that acknowledges suffering's reality and somehow harmonizes it into beauty? what is the contemplative path in this regard in your mind?

I've got some developing thoughts on these questions myself from a Whiteheadian perspective, but would be very curious to hear your thoughts! I know this developed into a pretty large inquiry, but I am curious to see what you think about this! Thanks so much!

Response: Jay McDaniel

Four great questions. You are so nice to care about my opinions. Here they are for what it's worth. I'll put your questions in quotations and mine outside quotations so that others may follow the conversation without too much re-reading of past posts.

1. "is evil an eternal object?"

No. The eternal objects are pure potentials and they are of two kinds – objective dealing spatio-temporal relations and subjective, dealing with subjective forms or emotions by which we respond to situations. These pure potentialities are not in themselves normative. There is not a pure potential called “truth” or a pure potential called “goodness” or a pure potential called “beauty.” Here Whitehead is different from Plato. Truth and Goodness and Beauty pertain to relationships between such potentialities and the actual world. For example, the emotion of anger may be “good” in some circumstances but “evil” in others. The wisdom of God is to avail us of possibilities which, relative to circumstance, are good and true and beautiful.

What is evil? From my own Whiteheadian perspective evil is two things: (a) debilitating suffering for which no subsequent goods can compensate, as in the suffering of the holocaust, and (b) missed potential, as occurs, for example, when an alcoholic who could have been a good parent misses that potential. Thus understood, evil is quite real, including for God. The idea that it is unreal is, for me, false. Having some experience in contemplative traditions myself, both Christian and Buddhist, I don’t see any reason to assert the contrary. The western idea that evil is merely an absence of God, or unreal as such, derives from neo-Platonic ways of thinking, but not from biblical ways of thinking. The idea itself betrays the experience of so many who do indeed suffer in debilitating ways or from a genuine sense that what could have been, was not.

What is evil? From my own Whiteheadian perspective evil is two things: (a) debilitating suffering for which no subsequent goods can compensate, as in the suffering of the holocaust, and (b) missed potential, as occurs, for example, when an alcoholic who could have been a good parent misses that potential. Thus understood, evil is quite real, including for God. The idea that it is unreal is, for me, false. Having some experience in contemplative traditions myself, both Christian and Buddhist, I don’t see any reason to assert the contrary. The western idea that evil is merely an absence of God, or unreal as such, derives from neo-Platonic ways of thinking, but not from biblical ways of thinking. The idea itself betrays the experience of so many who do indeed suffer in debilitating ways or from a genuine sense that what could have been, was not.

2. "if so, how could it be that god, in holding out pure potentials for a becoming world could contain within the divine mind potentials for evil and still be called 'good' in any sense of the word? are humans who actualize "evil" thus following a lure of creativity rather than god? or is there another solution?"

As said above, the pure potentials are not normative. When we choose evil over good, let’s say hatred over compassion, the choice is not lured by God or, for that matter, by creativity as such, since it is not a lure in the first place. Our choice may well be influenced by countless forces in our past, conscious and unconscious, and some from society. We may be tempted by other lures coming from other sources, including decisions we ourselves have made in the past, but the temptations are not from God.

3. "Are human emotions real or actual in any metaphysical sense?"

Yes. Emotions are subjective forms and they are as actual as anything else metaphysically. Much depends on what is meant by metaphysical, but if we simply mean part of the actuality of the universe, we best say yes. Additionally, emotions can carry forms of wisdom: e.g. the wisdom of knowing others; the wisdom of sensing connections; the wisdom of wonder and awe; the wisdom of hope. They can carry “metaphysical” wisdom. The denial of this is part of a western dualism that I think Whitehead helps us overcome.

4. "And, lastly, perhaps a more pedagogical question...how is one to move through their human journey with its emotional and embodied events of suffering into a place of peace? is it by detachment or psychical distancing? or is there some other integration of the reality of "actual" or "real" suffering into one's perspective that acknowledges suffering's reality and somehow harmonizes it into beauty? what is the contemplative path in this regard in your mind?"

In general, I think integration is the best option, Tim. Although I think there are occasions when distancing, or anesthetizing, may be the best option. There’s no universal here; we must be sensitive to what helps a person deal with the suffering at hand. But all things considered, and in many circumstances, there is no need to hide from suffering that is inescapable, but our response to suffering can itself be beautiful even amid the suffering, as when we respond with courage or sheer endurance. And often, suffering can become grist for a subsequent wisdom and love, which would not have occurred otherwise, even if, all things considered, we still wish it hadn’t occurred. Additionally, I myself think that, in faith, we can hope that it is somehow transformed into a harmony of harmonies (the consequent nature of God) which includes tragedy. I think we can also feel this harmony of harmonies sometimes as an inner peace.

HELPFUL READINGS IN PROCESS THEOLOGY

Question - What Books Might Be Suggested?

Wikipedia - C. Robert Mesle (born 1950) is a process theologian and was professor of philosophy and religion at Graceland University in Lamoni, Iowa until his retirement in 2016. After earning a B.A. in religion at Graceland University (1972), an M.A. in Christian theology at University of Chicago Divinity School (1975), Mesle received a Ph.D. in philosophy and religion from Northwestern University (1980).

Mesle is the author of Process Theology: A Basic Introduction. In this book he outlines three attributes of a process theology. There is a relational character to the divine such as:

* * * * * * * * * * * *

HELPFUL READINGS IN PROCESS THEOLOGY

Question - What Books Might Be Suggested?

Wikipedia - C. Robert Mesle (born 1950) is a process theologian and was professor of philosophy and religion at Graceland University in Lamoni, Iowa until his retirement in 2016. After earning a B.A. in religion at Graceland University (1972), an M.A. in Christian theology at University of Chicago Divinity School (1975), Mesle received a Ph.D. in philosophy and religion from Northwestern University (1980).

Mesle is the author of Process Theology: A Basic Introduction. In this book he outlines three attributes of a process theology. There is a relational character to the divine such as:

- God experiences both the joy and suffering of humanity.

- God is not omnipotent in the classical sense

- God exercises relational power and not unilateral control.

No comments:

Post a Comment