|

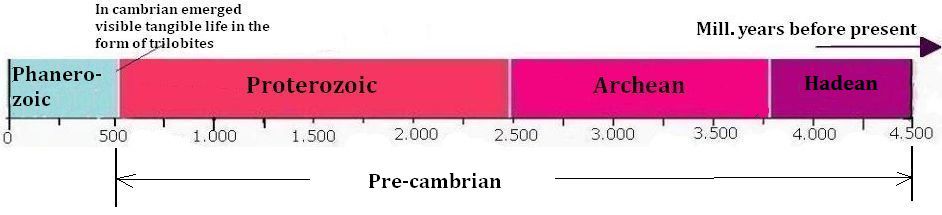

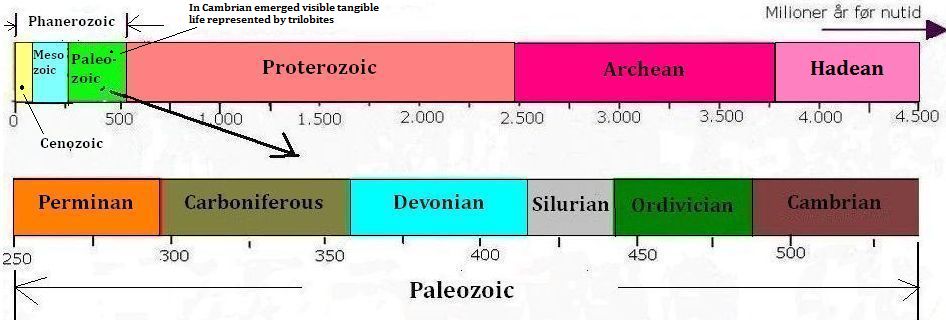

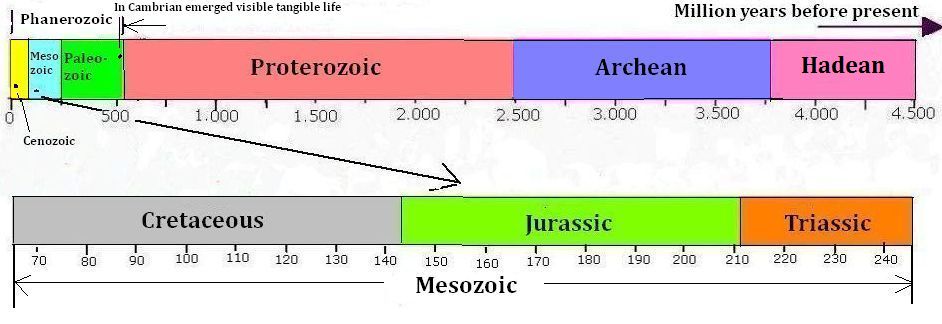

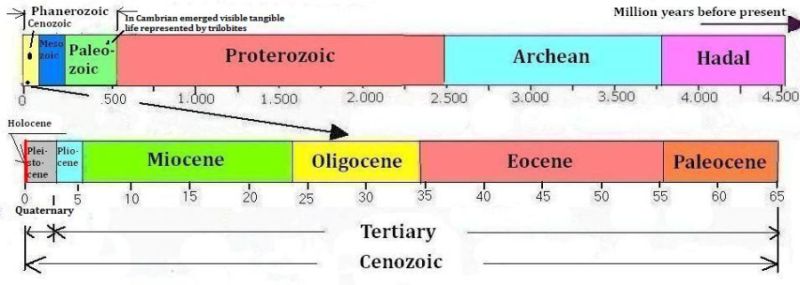

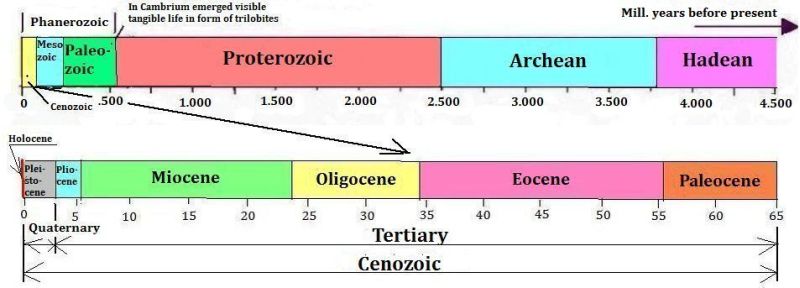

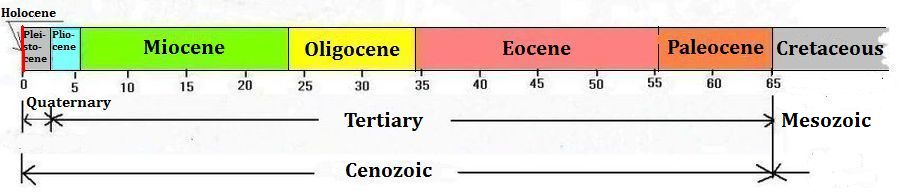

| This diagram by the study authors shows how climate change driven by astronomical forces — such as tilt in the earth’s axis and changes in the shape of the Earth’s orbit around the sun — has influenced ice ages and consequently, human evolution. Photo: Nature |

Climate change and us: What really shaped

human evolution last 2 million years

Climatic shifts determined where food was available, driving

migration and adaptations, according to the study

Published: Thursday 14 April 2022

[edits & arrangements mine - re slater]

Ancient humans likely evolved in response to climate shifts by settling and adapting to newer habitats, according to a new study.

Climate change driven by astronomical forces — such as tilt in the Earth’s axis and changes in the shape of the Earth’s orbit around the sun — has influenced how much solar radiation reaches the planet, the study published in Nature noted.

This spurred the Ice Age and the warmer interglacial periods, according to researchers. These climatic shifts determined where food was available, driving migration and adaptations, the study noted.

“Astronomically-forced past climate change determined where ancient humans lived and how their habitat and food-preferences changed over time due to adaptation,” Axel Timmermann, lead author of the study and director of the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP) at Pusan National University in South Korea, told Down To Earth.

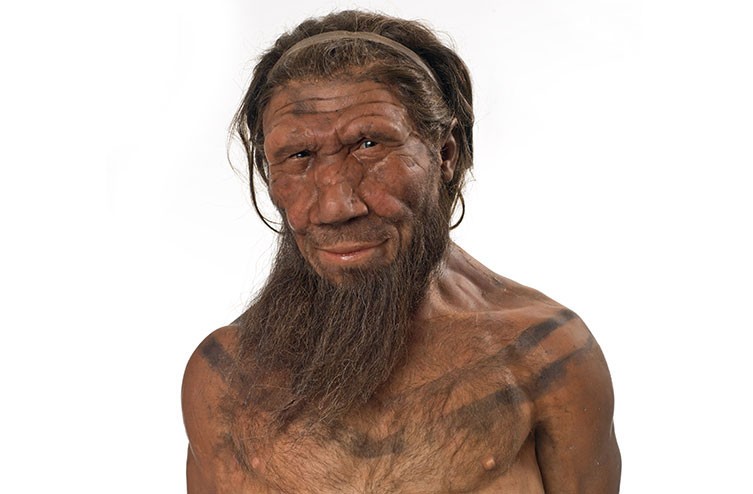

The researchers mapped the habitats of five human lineages: Homo neanderthalensis, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, African Homo — Homo habilis and Homo ergaster — and Homo sapiens.

Previous studies have investigated the link between climate change and human evolution. Even though the idea is old, there has been very little hard data to support this hypothesis quantitatively, Timmermann added.

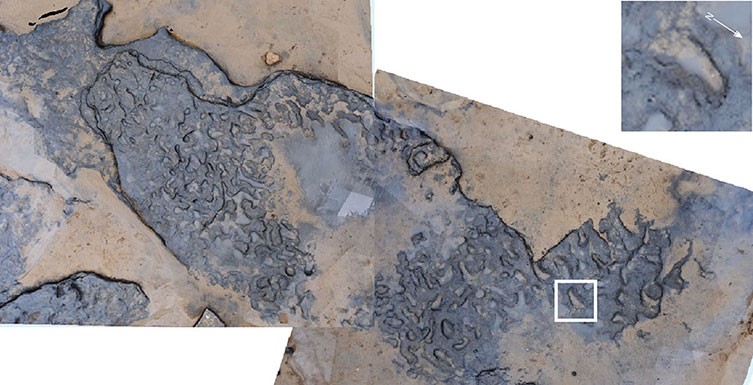

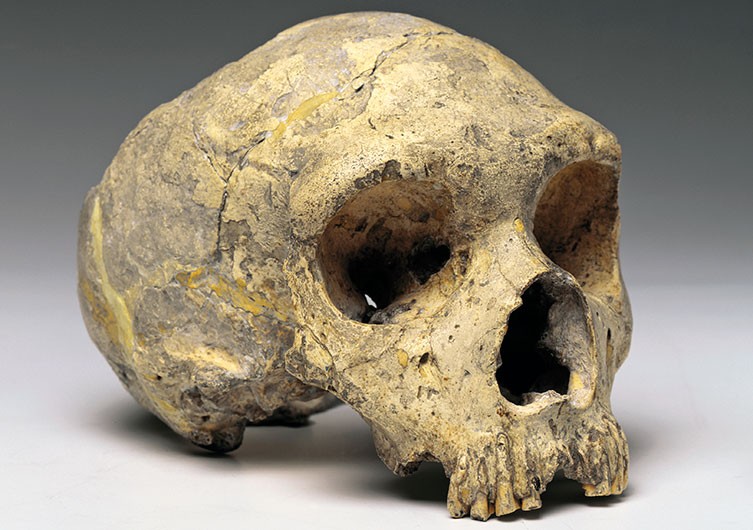

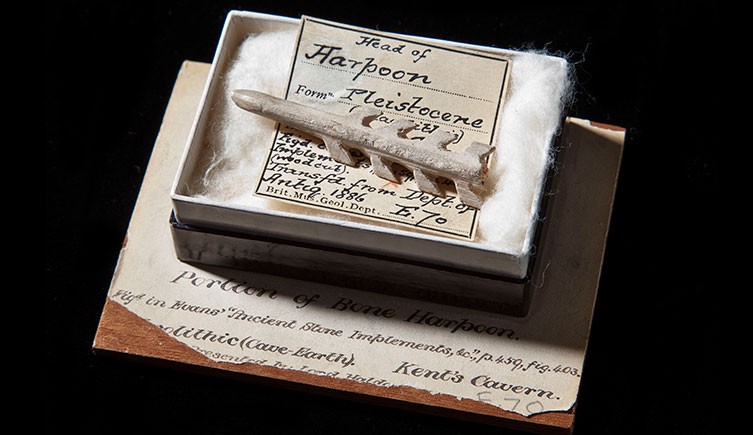

The researchers tried to address this gap by combining data on well-dated fossil remains and archaeological artefacts. A supercomputer helped them reconstruct the earth’s climate history over the past two million years.

According to their analysis, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens had the most extensive habitats:

- While Neanderthals were more concentrated in Europe,

- the early African homo found refuge in eastern and southern Africa.

- Homo heidelbergensis settled in southern Africa, east Africa, and Eurasia [(e.g., The Levant/India - re slater)], the study determined.

Though all five human species showed a preference for a particular habitat, they responded to climate shifts, the researchers highlighted.

For example, Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals had to migrate from Northern Europe when ice ages made the region cold and dry, Timmermann explained.

So, they moved south to the Mediterranean, which had enough food available. When glacial conditions ended, forests moved northward quickly, and so did animals and Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals, he added.

Timmermann and his colleagues also found that around two to one million years ago, early African hominins preferred stable climatic conditions, staying back in narrow habitable corridors.

Homo heidelbergensis, on the other hand, migrated and adapted to make use of a much wider range of available food resources in new environments. A major climatic transition about 800,000 years ago triggered this migration, the study found.

“Archaic humans either had to adapt to the new environment or migrate to different regions,” Timmermann said,

Homo heidelbergensis became global wanderers by reaching remote regions in Europe and eastern Asia, Elke Zeller, PhD student at Pusan National University and co-author of the study, said. “Climate conditions are strongly connected to food security,” Timmermann added.

The researchers also went a step further by documenting when and how one species developed into another. When major ice age cycles began, Homo heidelbergensis split into two groups: European and African, the study suggested.

Around 400,000-500,000 years ago, the European group may have gradually evolved into Neanderthals, Timmermann pointed out.

And around 200,000-300,000 years ago, the African group likely developed into the earliest Homo sapiens in the southern [(and eastern - re slater)] part of the continent, according to the study.

Persistent harsh climate conditions could trigger a gradual transition from one species to another, the expert added.

In the future, the team plans to gain a clearer picture of ancient humans by studying the impact of past climate change on human genetic diversity, Timmerman said.

* * * * * * *

1:07:31

Brave New Prehistoric World

Premiered May 4, 2023

Recent breakthroughs in dating ancient samples of DNA and human remains have led to a radical reassessment of human origins.

At least ten other early human groups–some with the cognitive capacity to make art, jewelry and herbal medicines–occupied the planet at the same time as our ancestors, Homo Sapiens, and some of their genomes live within us today.

Leading archeologists and paleoanthropologists join Brian Greene to discuss how these surprising new insights are transforming our understanding of early Humans.

This program is part of the Big Ideas series, supported by the John Templeton Foundation.

Participants: Rebecca Ackermann Thomas Higham Sheela Athreya Viviane Slon

* * * * * * *

Rewriting the Story of Humankind

0:02 / 1:40:51

Rewriting the Story of Humankind

Premiered Jun 9, 2023

What attributes set our species apart? Taming fire? Expressing artistically? Solving problems creatively? Recent discoveries that have already upended humankind’s origin story by expanding our family tree, are now challenging long-held assumptions about what makes us special.

Paleoanthropologist Lee Berger is a leading figure in these breathtaking developments and he joins Brian Greene to discuss how new discoveries are now rewriting human history.

This program is part of the Big Ideas series, supported by the John Templeton Foundation.

The live program was presented at the 2023 World Science Festival Brisbane, hosted by the Queensland Museum.