|

| "The Empire is Making You Sick" |

Radical Christian Process Theology, Part 1

"The Empire is Making You Sick"

by R.E. Slater

"Faith in the transcendent God of traditional Christian theology is no longer possible for the contemporary man. The theologian can no longer work in the church. His concerns are no longer the classical churchly concerns: liturgy, prayer, otherworldly salvation. He must move out into the world, since, like other contemporary men, his fundamental preoccupation is the struggle to maintain human values in the context of modern secular society. He can no longer speak of a God who has become meaningless to contemporary man but he must still speak of Christ. The Christ of the radical theologian, however, is the purely human Christ who is the man for others. Christ's function in contemporary society is to serve as a supremely inspiring human example, Christ is "a place to be" in the struggle for human values." - Excerpt: Encyclopedia.com

Introduction

The whole premise of Radical theology is the deep feeling that the God of traditional Christianity can no longer be known within the church as it holds onto its religious methodologies and belief structures in such a way as to prohibit uncertainty and doubt and humanitarian values most required in a Christian religion popularly believed to require but the highest of forms of certainty and belief.

That this churchly covenant bound in blind trust and dogmatic legalism between itself, and the God it worships, must come first-and-foremost above all other succeeding commitments and behaviors - even that of humanitarian acts of social justice and equality which are most dearly desired across all areas of human endeavor and civilization. That the church's institutes are to be upheld firstly above all else. To be protected and defended by every means possible. And must always be decrying itself to be in a continual state of victimhood to society at large.

Responses to the Christian Church

This is the nub of argument by the secularized modernistic Christian Church clutching to its secularized spiritual faith to which the faithful postmodern Christian response adamantly declares in opposition that "It doesn't know, and wishes to explore, even through speculation, the realms of the Christian faith beyond its own self-avowed dogmatic words and actions." That uncertainty and doubt are the only good epistemic tools in which to do theology and to be Christian in the Christianly sense.

> Radical Theology

It is also where the postmodernal Protestant and Catholic Christian theology of radical theology begins when declaring the Christian faith bankrupt to it's highest sentiments and beliefs when seeking to re-envision the Christian faith "outside of itself" in order to see itself the more clearly. That this critical theological response might more resemble the approaches of non-Christian, agnostic, or atheistic radical responses than their Christianly antecedents when seeking a more holistic, more benevolent, Christian faith than what could be found in the present haggered religious aspects of modernal Christianity become a mere "empire-like" religion rather than a humbling, penitent, living faith.

> Progressive Christianity

At this same time, diverse theological branches arose from within mainline denominational Protestant and Catholic Churches identified broadly as Progressive Christianity. And when it became embraced by convicted evangelical church structures it took on a new identity known as Emergent Christianity birthed between the 1990s-2010s. Afterwhich the mainline and emergent streams of progressive Christianity merged together to simply be known broadly as Progressive Christians more deeply concerned with the positive-and-proactive Christianly behaviors of humanitarianism, social justice, and equality than they were with ostracizing and other-worldly Christian dogmas and sentiments.

> Process-based Christianity

Yet another obscure group was arising from the 1940s and 50s with the same radical and progressive concerns as their compatriots but with a unique signature which declared Westernized (secular) Christianity to be unhelpful and Continental Christianity too widely dispersed to offer any further corrective insight and faith living beyond its own cultural era. This body of Christians came to be known as Process-based Christians but (i) unlike Radical Christians preferred to stay within the traditional garments of the Church when critiquing its hoary structure while (ii) also sweeping up unto itself the many Progressive concerns of denominational and evangelical communities.

The unique signature of a Process Christian went one step farther than the Radical Christian or Progressive Christian when announcing that the philosophical-theological foundations upon which the traditional Westernized church had built itself upon over the past 2000 years was inadequate to the postmodernal task lying ahead of itself. That in order to break away from its rising secularism it needed to re-examine its own non-processual philosophic-theologies and declare them anathema to the Westernized Church.

That it's traditional theological underpinnings had absorbed all the wrong elements of human belief about God, humanity and creation. That a more organic, more relational, philosophy focused upon the presence of the Divine-Human-World Cooperative must come to the fore of the Church's theology. That a solidarity between God, man, and creation be perceived and taught unlike the church's traditional theistic dogmas claiming theistic absence and wrathful judgment. And if done, then Christian humanism, social justice, and equality would naturally rise up within Westernized Analytic and Continental forms of theology centered in Love and not in proscript. One which would remove religious fidelity to unnatural church laws and church attitudes which had plagued its theologic structures since the days of Jesus.

> Summary

Consequently, the Christian branches of radical theology, Christian progressivism and Christian process theology found a more natural home with one another including a sympathetic nod to those radical theologians who in later generations have found themselves outside of the church doing the work of religious deconstruction and reconstruction for the purposes of recovering a humanely ethic of loving response, cooperative sharing, peace, and goodwill between all elements of humanity embraced by a plurality of religions and enculturations.

Moreover, process Christians believe that progressive Christians would find a greater fidelity with process theology which naturally underlays their beliefs than they would find with evangelical theologies which steer away from the foundational factors of Love into their own foundations of Christian dogma which hold the idea of love more loosely to their version of a God who sometimes loves but not always.

Modern v Postmodern v Metamodern

With the era of modernism came the era of Empire into the Christian faith. In this way the secularism which the traditional church disavowed became accepted and its modis operandi for doing the work of theology and mission.

Conversely, Radical Christians saw worldly Empire for what it was in light of the German Lutheran Churches embrace of German Nazism and its zenophobic and "white supremacy" responses towards non-Europeans, minorities, and ostracized humans. It became a radicalized form of Bonhoeffer's plea to the Church to not submit itself to evil and horror. Radical Christianity took Bonhoeffer's plea from his dead lips as he hung on the German SS gallows and spread his message in deep distrust of the Church's message and motives. It dissented and proclaimed God's death on the hand of those given to preach God's life in the midst of Empire.

Likewise, the Christian humanism which was active across Victorian England was spreading its way westward into America and southward into Europe. It declared that women had value and must vote; that children should not be working but in school; that the Enlightenment society of Western culture was neither so much enlightened nor helpful in breaking down human oppression and the invisibility of those minorities unwanted and overlooked.

To this history of Christian humanism came the Civil Race Riots of the 1960s under Martin Luther King (MLK) which re-established the urgency which Christian radicals had declared of the Church that it not repeat itself in America as it had in Nazi Germany. And in the 1990s the voices of Emergent Christians began crying out that the Christian humanism of the Westernized Church had been absorbed once again and without its former evocative voice for dissent and breakage to the church's embrace of Empire. That the Civil Reforms of the 1960s had been supplanted by the indolences of religion once again.

It was throughout this time of modernism giving way to its necessary and critical partner postmodernism that Process Christianity began to form in the Ivory towers of Christian and non-Christian universities. That Whiteheadian philosophic-theology offered a roadmap between the modernity-traps of Empire Christianity and the postmodernity criticisms of the Church.

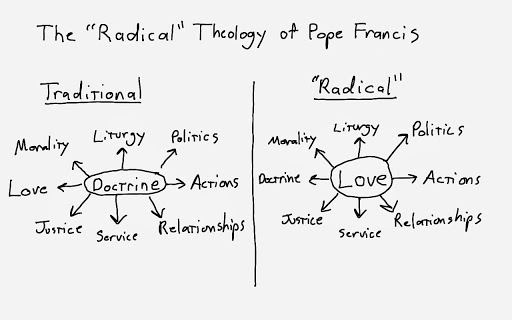

That the Christian God was firstly Loving and secondly Holy and Justice. That if either of the last rose to prominence than the Love which is God would lose out to Church practices overly focused on holiness and judgment as reflected in Catholic monasteries and Protestant attitudes towards civil dominions of its own theocratic rules over Constitutional democracies. Neither of which bore God's Love in its centers.

More recently, as metamodern has strode into today's postmodern Western cultures we are seeing the pendulum swings between one form of modernism to the other of postmodernism with meta- (middle) swinging in between these polar opposites. It is here where a process foundation again finds the more promise.

For one, Process Christianity recovers Divine Love in its Theology of Love (as versus a Theology of holiness or judgment):

- It keeps with the best traditions of Radical Christianity in critiquing Christianity as to its lusts for Empire and disregard for loving missionalization of God's Love.

- It picks up Progressive/Emergent theologies wanting humanitarian action, social justice and equality.

- It can work within all forms of civil governments without necessitating churchly religious dominionism (as opposed to crusades, inquisitions, jihads, fascism, acts of gender + minority oppression, etc).

- And, it can discourse with all forms of religious cultures prejudiced towards loving cooperation, sharing of resources, and solidarity of cause such as that of building ecological societies balanced in environmental and societal health in ways Capitalism and Communism, neo-Maoism and Apartheidism cannot.

This then is the promise of Process-based global sphere of loving outlook regardless of religion, economy, or political government when refusing the trappings of "empire" and political division, fear of polyplural enculturation and assimilation in world of climatic, ethnic, and resource turmoil.

Conclusion

In summary, Faith in the transcendent innured God of traditional Christian theology is no longer possible for the contemporary man seeking a God of Loving Presence.

Nor can the theologian work any longer in the church if the church cannot allow uncertainty and doubt which challenges it's faith.

For congregations to be simply concerned with liturgy, prayer, and otherworldly salvation in not enough; it must show itself by its teachings of Love and Loving outreach.

The metamodern Christian, like other contemporary elements of society, must find their struggle in the retention of human values against technocratic societies forcing non-relational, non-organic societies of individuals utilizing connective methods without living out those methods.

In a word, we must continually work at re-etabilishing flesh-and-blood fellowships with one another across our communities, businesses, and nature itself. To be a true Athenian who sought to be Wholly-whole without succumbing to the isolating practices of technocratically dominionistic and oppressive forms of religious and societal culture.

That when speaking of God we recognize God's Loving Presence in the daily lives of ourselves, others, and all parts of creation. That a transcendent God is simply another name for a God who has removed himself from his duties of Love which he can never do as promised to Abram in the covanently cut halves of sacrifice (Gen 14) and the work, ministry, life, death, and resurrection of God's Self in Jesus.

To recognize that like Ghandi, Jesus as the God-man had the high hopes of overturning religion gone wrong. But more than Ghandi, Jesus was also the God who sacrificed himself that Love might Win.

"Faith in the transcendent God of traditional Christian theology is no longer possible for the contemporary man. The theologian can no longer work in the church. His concerns are no longer the classical churchly concerns: liturgy, prayer, otherworldly salvation. He must move out into the world, since, like other contemporary men, his fundamental preoccupation is the struggle to maintain human values in the context of modern secular society. He can no longer speak of a God who has become meaningless to contemporary man but he must still speak of Christ. The Christ of the radical theologian, however, is the purely human Christ who is the man for others. Christ's function in contemporary society is to serve as a supremely inspiring human example, Christ is "a place to be" in the struggle for human values." - Encyclopedia.com

R.E. SlaterMay 21, 2023

edited May 27, 2023

* * * * * *

by G. McCool

Radical theology was the name applied in the 1960s to a widely publicized current in American Protestant theology which was fundamentally skeptical about modern man's ability to speak meaningfully about God.

The theologians most prominently identified with the movement were William Hamilton, Paul Van Buren, and Thomas J. J. Altizer. Several other theologians were closely associated with the movement in the popular mind although their works were less radical in character. The British theologian, John A. T. Robinson, and the American theologian, Harvey Cox, shared a good deal of the radical theologians' skepticism and, like the radical theologians, Robinson and Cox advocated a religion of secular involvement rather than a religion of otherworldly salvation. Gabriel Vahanian, although not one of the radical theologians, shared their preoccupation with the challenge of contemporary secularism to Christian faith.

The theological divergencies among the radical theologians were too great for them to form a school. Nevertheless, their works are marked by a number of common convictions:

- Faith in the transcendent God of traditional Christian theology is no longer possible for the contemporary man.

- The theologian can no longer work in the church. His concerns are no longer the classical churchly concerns: liturgy, prayer, otherworldly salvation.

- He must move out into the world, since, like other contemporary men, his fundamental preoccupation is the struggle to maintain human values in the context of modern secular society.

- He can no longer speak of a God who has become meaningless to contemporary man but he must still speak of Christ.

- The Christ of the radical theologian, however, is the purely human Christ who is the man for others [beyond the Church's pale or Society's interest. - re slater].

- Christ's function in contemporary society is to serve as a supremely inspiring human example, Christ is "a place to be" in the struggle for human values.

The shift away from theological activism at the end of the [1950-60s] civil–rights struggle brought a decline of interest in radical theology. As a movement it did not survive the sixties, but the issues which it brought to prominence in America, e.g., the knowability of God, contemporary Christology, eschatology, and social activity, continue to occupy the attention of contemporary theologians.

---

See Also: death of god theology.

Bibliography

t. j. j. altizer,

The Gospel of Christian Atheism (Philadelphia 1966); ed.,

Toward a New Christianity: Readings in the Death of God Theology (

New York 1967).

t. j. j. altizer and w. hamilton, Radical Theology and the Death of God (Indianapolis 1966).

h. cox,

The Secular City (

New York 1965).

w. hamilton, The New Essence of Christianity (New York 1961); "The Death of God Theology," Christian Scholar 48: 27–48; "The Shape of Radical Theology," Christian Century 82:1219–22.

j. a.t. robinson,

Honest to God (Philadelphia 1963);

Exploration into God (

Palo Alto, Calif. 1967).

g. vahanian, The Death of God (New York 1961); No Other God (New York 1966); ed., The God is Dead Debate (New York 1967).

p. van buren, The Secular Meaning of the Gospel (New York 1963); Theological Explorations (New York 1968).

l. gilkey, Naming the Whirlwind: The Renewal of God Language (Indianapolis 1969) 107–145.

v. mehta, The New Theologians (New York 1966).

t. w. ogletree, The Death of God Controversy (Nashville 1966).