A great lecture by Arthur F. Holmes

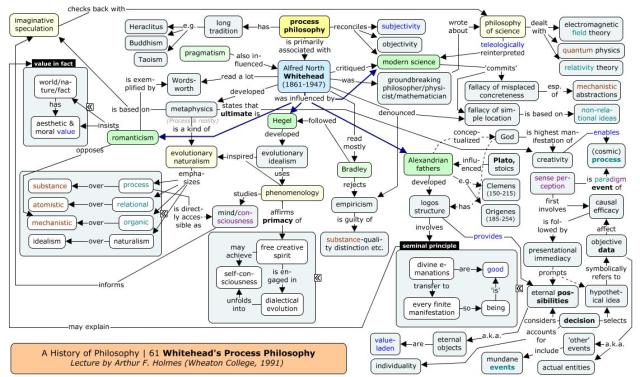

At the end of my last post (no, not that last post!) I admitted to my predilection for Whitehead, the father of process philosophy and theology. Unfortunately, his magnus opus, Process and reality, is notoriously difficult. Accidentally, I came across a playlist with a lecture series on the history of philosophy by Arthur F. Holmes (The playlist also includes lectures on Leibniz, Locke, Kant, Hegel and American pragmatism, which I will probably use as a background when I will deal with Churchman’s “The design of inquiring systems”). I found the first lecture on Whitehead (there are three in total) greatly elucidating, especially after I made a concept map (see below) of the lecture. I also made a transcription of the lecture, which you can download here. What follows in this post is a short description of the concept map, so a very, very brief introduction to Whitehead’s process philosophy. Best listen to the lecture, while keeping the concept map, the transcription, and possibly this post handy. You may learn something in a jiffy that others (really, really clever guys and gals) have taken months to master.

Process philosophy … is nothing new. Process notions can be found in many traditions, including Buddhism (India), and Taoism (China), but also in the ideas of the pre-Socratic Heraclitus (Greece, 535-475 BC). Process philosophy in its modern guise was formally launched in 1929 when Whitehead (1861-1947) published his Process and reality.

Alfred North Whitehead … was a ground-breaking philosopher (of science), physicist and mathematician from Thanet in Kent, UK. His main influences as a philosopher were modern science, Hegel, 19th century Romanticism and the Alexandrian fathers. His prime concern is the distinction between science and ethics, the separation of value and fact, a problem that also troubled Churchman (hence perhaps my liking of the two).

Mathematician and physicist While in Cambridge he wrote Principia mathematica with Bertrand Russell. While teaching at London University he wrote about quantum physics and relativity theory. He reformulated the relational implications of both in a number of fallacies of science, including the fallacy of misplaced concreteness (esp. in relation to mechanistic abstractions) and the fallacy of simple location (which is based on non-relational ideas).

Hegel’s influence … came to Whitehead mostly through the work of F.H. Bradley, a British idealist philosopher, who rejected empiricism – as did Whitehead. Hegel´s philosophy is best characterized as evolutionary idealism, in which the ‘free, creative spirit’ unfolds into self-consciousness using the well-known triad of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. This spirit is not a substance or thing, but a process, which Hegel studies by means of a phenomenology of human existence and history. Whitehead borrows most of these ideas from Hegel, with the exception of the ‘spirit’ idea (idealism). He is staunchly monistic (as am I) and prefers his evolutionary process to be naturalistic.

The evolutionary naturalism … of Whitehead emphasizes process (instead of substance), relations (instead of non-relational, atomistic things), and an organic world view (instead of a mechanistic universe). Whitehead also adopts a phenomenological approach to the study of process as the basic notion of reality. His main subject of phenomenological study is human consciousness, as it is most directly accessible to us.

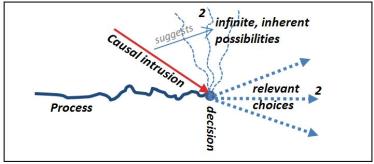

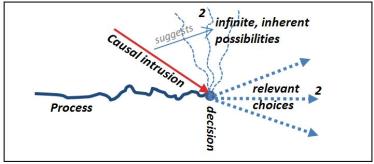

Sense perception Of all the processes that make up human consciousness, Whitehead uses sense perception as the paradigm event to exemplify all the processes that constitute the universe. Whitehead’s theory of where our ideas come from differs from that of many of his predecessors. Sense perception follows from the intrusion of real, objective

data (first step), which prompt us to consider a range of possibilities (second step) as to what this intrusion amounts to. In a third step, we select one of these possibilities or ideas as our ‘working hypothesis’. This hypothetical idea symbolically refers to the objective data that intruded upon our consciousness in the first place, be it by way of sound, touch, vision or otherwise. Whitehead is without doubt a realist (or naturalist) and not an idealist.

Eternal possibilities The question now is as to where the possibilities of the second step come from? One could say it comes from our “stock of experiences”, as Dewey suggests. Whitehead prefers them to come from the so-called “logos structure” of God as developed by the Alexandrian church fathers such as Clemens and Origenes in the 2nd and 3rd century CE. These possibilities are possibilities of novelty that must have been created in some way. Without novelty no creative process is possible. To Whitehead God is the highest manifestation of creativity, whose stock of possibilities drives the cosmic process of creation. Whitehead does not claim any knowledge of the starting or end point of creation. On the basis of the evidence available to us there is only on-going creation.

Value … can be observed at two points. In the first place in the range of possibilities, each of them being value-laden, whether it is for good or for bad. The second point is where we opt (or decide) for one possibility or the other. Whitehead wanted a cosmology that has a place for value. Modern science claims itself to be value-free by restricting itself to the facts and nothing but the facts, whereas Whitehead experiences aesthetic and moral value in the world and in nature. This experience of value is also expressed in Romanticism as exemplified by e.g. Wordsworth, whose poetry was a source of inspiration for Whitehead.

Process theology Whitehead’s metaphysics has greatly inspired Christian theology and perhaps the theologies of other faiths. Important process theologians include Charles Hartshorne (1897-2000) and John B. Cobb (1925), who co-founded the Center for Process Studies with David Ray Griffin (1939) in 1973. Dr. Cobb maintains a blog, answering questions regarding process thought and faith. A very pleasant introduction to process theology is the one by C. Robert Mesle. The Divinity School of the University of Chicago was the place where process theology developed for at least 60 years.

Criticism … of Whitehead and process philosophy comes from a variety of sources. Whitehead’s early friend and collaborator, Bertrand Russell, obviously criticized the theological aspects of process philosophy, since he believed religion to be little more than often harmful superstition. Arthur Holmes (who delivered the Youtube lecture on which most of the concept map of this post based) thinks Whitehead may have stretched his event-based monism too far by applying it to persons.

God Whitehead leaves many questions on the nature of God unanswered. Perhaps he did so on purpose, to leave open the possibility of process naturalism as suggested by Mesle, who holds that “the world of finite, natural creatures is unified”, but not “in such a way as to give rise to a single divine Subject,” even of a non-supernatural kind as in process theism. A naturalistic God then may be conceived as the subjective projection of a unified world of finite, natural creatures, i.e. an ideal without the unified existence ascribed to it by theists, but well worth approximating as a conception in one way or another. Such a conception leaves ample room to position oneself as an atheist, agnostic or theist, all the while producing a lot of common ground between the three.

Appreciation There can be no doubt that Whitehead’s philosophy is a valiant effort to bring value or the human quest for meaning and fact or the scientific quest for truth together in a single scheme. The scheme as a whole cannot be understood and appreciated by looking at it from a single angle. Taking human consciousness as a starting point for obtaining a phenomenological description of a paradigm event of cosmic process, both at macro-scale and micro-scale, as well of human as of divine reality, was brilliant. Once theism is accepted, then the logos structure gives it a new twist (panentheism) that inspired many theologians, including Wieman and untold (not just Unitarian) others. There is also the romantic view of aesthetic and moral value in nature, which aligns well with this type of panentheism. Bertrand Russell, despite his criticism, could not possibly disprove of that.

Systems approach What I like about the phenomenological description of the “paradigm event” of process is the way it fits with the systems approach. It is important to note that an event can be anything, from somebody’s biography (or life) to the history of the universe. A systems version of Holmes´ account of an event could be: a process (or project or policy) that experiences an intrusion of sorts (a “wicked problem”), which then may become the subject of an inquiry in a systemic way to suggest an infinite range of possibilities, which enables a decision in favour of one option or another. Another aspect of process philosophy is its process-relational vision, its view that reality is relational, through and through. Reality as a social process. Freedom is inherent in the world. To be an individual is to be self-creative, i.e. to take decision after decision. Furthermore, in Mesle’s words, “Experience is rich and complex. The clarity of sense experience is grounded in deeper but vaguer experiences of our relatedness to the world process. Adequacy to this wealth of experience [SH: which can be tapped by taking into account the perspectives of others] is the ultimate test of our ideas.” The value of the systems approach lies in its potential for finding better approximations to such adequacy.