"Reading sacred poetry is a time-honored spiritual practice. If you'd like to incorporate it into your devotions, we have many resources at Spirituality & Practice for you."

Thus write Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat in the world's most inclusive interfaith resource center, the website Spirituality and Practice. Every April for the last seven years, during National Poetry Month in the United States, they have offered thirty poems for interfaith readers. I have compiled the poems into one list of 210 poems, with links to their site for each poem. Enjoy.

- The Sun Never Says by Hafiz

- One Song by Rumi

- Metamorphosis by May Sarton

- Attachment by Vasant Lad

- Questions by Ghalib

- Ryokan and Mary Lou Kownacki

- Hum by Mary Oliver

- All That Is Joy by Rabindranath Tagore

- My Joy by Rabi'a

- Haiku by Buson and Issa

- Ecstatic Poems by Kabir

- Beauty and Ugliness by Lao Tzu

- Waging Peace by Sarah Klassan

- The Same Inside by Anna Swir

- Tears by Svein Myreng

- That Nature Is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection by Gerard Manley Hopkins

- There Is No Road by Antonio Machado

- Don't Make Lists by Dorothy Walters

- Aware by Denise Levertov

- 1979 by Wendell Berry

- I Like You by Kevin Anderson

- Roll Call by William Stafford

- Stone by Charles Simic

- For What Binds Us by Jane Hirshfield

- Love after Love by Derek Walcott

- Healing by Joseph Bruchac

- Ars Poetica by Blaga Dimitrova

- Earth Verse by Gary Snyder

- The Good News by Thich Nhat Hanh

- Hold on to April by Jesse Stuart

- Trees Can Be Our Teachers by Satish Kumar

- Live With the Spirit by Jessica Powers

- Sixty-Four by Daniel Skatch-Mills

- Open the Window by Rumi

- Fern-Leafed Beech by Moyra Caldecott

- Wild Things by Wendell Berry

- Three Poems on Presence by Baisao

- Miracles by Daniel Berrigan

- Butterflies by Siegfried Sassoon

- Living by Denise Levertov

- Goodnight by Carl Sandberg

- Two Prayers on Grace by James Vanden Bosch

- What Is the Greatest Gift? by Mary Oliver

- Three Poems on Hope

- Not Enemies by Stephen Levine

- Olive Trees by Marilyn Chandler McEntyr

- Split the Sack by Rumi

- The Earth Is Waiting For You by Thich Nhat Hanh

- Surviving Has Made Me Crazy by Mark Nepo

- On Forgiveness by Karyn Kedar

- Morning Has Broken by Eleanor Farjeon

- Rendition of Psalm 41 by Nan Merrill

- Welcome Morning by Anne Sexton

- Love Poems by Susan Landon, Ann Reisfeld Boutte, and Susan R. Norton

- First Night by Julia Ackerman

- An Atom of Love by Yunus Emre

- Dear Diary by Leonard Cohen

- Freedom to Marry by Barbara Hamilton-Holway

- Four Sufi Poems

- Icon by Mary Rose O'Reilley

- Ecstasy by Hayden Carruth

- Love Sonnet by Pablo Neruda

- The Layers by Stanley Kunitz

- Let Evening Come by Jane Kenyon

- The Answering Machine by Linda Pastan

- Soil by Richard H. Goodman

- Zero Circle by Rumi

- The True Nature of Your Beloved by Hafiz

- Sweet Darkness by David Whyte

- Gift by Czeslaw Milosz

- A poem by Mirabai

- A poem by Lalla

- A poem by St. Catherine of Siena

- A poem by Meister Eckhart

- Against Certainty by Jane Hirshfield

- Serenity Is Not by Katherine Swarts

- Oneness by Thich Nhat Hanh

- A poem by William Stafford

- A poem by Mary de La Valette

- A Place to Sit by Kabir

- Living in Hope by Suzanne C. Cole

- A poem by Jim Cohn

- Who Knows What Is Going On? by Juan Ramon Jimenez

- The Guardian Angel by Rolf Jacobsen

- It Is That Dream by Olav H. Haug

- Questions by Peter Dixon

- Have You Not Heard His Silent Steps? by Rabindranath Tagore

- God's Name by Tukaram

- Sometimes by Hermann Hesse

- There You Are by Rumi

- Earth, Sister Earth by Dom Helder Camara

- The Way They Held Each Other by Mira

- A Cushion for Your Head by Hafiz

- Annunciation by Marie Howe

- Just Stop by Baba Afdal Kashani

- That Passeth All Understanding by Denise Levertov

- Summing Up by Claribel Alegria

- After the Sea by John O'Donohue

- The First Book by Rabindranath Tagore

- The Clay Jug by Kabir

- White Apples by Donald Hall

- In the World by Brigid Lowry

- A poem on Love by Kabir

- Remember by Joy Harjo

- Nothing Much by Allison Harris

- A poem on silence by Baisao

- Peonies at Dusk by Jane Kenyon

- Reasons to Meditate by Lisa Cullen

- The First Book by Rita Dove

- A poem on abundance by St. Catherine of Siena

- Soil by Richard H. Goodwin

- Seeking Your Trace by Fakhr al-Din Iraqi

- Vision by May Thielgaard Watts

- A poem on devotion by Mary Lou Kownacki

- A poem on kindness by Margaret Jain

- A poem on transformation by Hugh Robert Orr

- What Does Light Talk About? by St. Thomas Aquinas

- Love Is by May Swenson

- Leisure by W. D. Davies

- Gift by Czeslaw Milosz

- The Old Elm Tree by the River by Wendell Berry

- Love at First Sight by Wislawa Szymborska

- Never Lose the Way by Shihab al-Din Yahya Suhrawardi

- Living the Scriptures by Lalla of India

- So Much Happiness by Naomi Shihab Nye

- There Is a Wonderful Game by Hafiz

- Poetry by Pablo Neruda

- On Ordinary Daily Affairs by Layman P'ang

- A Kiss by Deborah Garrison

- Is My Soul Asleep? by Antonio Machado

- On Mother Earth by Jamie Sams

- When Your Life Looks Back by Jane Hirshfield

- Memory by Jorge Luis Borges

- Ask Me by William Stafford

- Briefly It Enters, and Briefly Speaks by Jane Kenyon

- A poem - prayer about love and life by Kuan Tao-sheng

- A poem-prayer for solidarity and justice by Arthur Waskow

- Growing older with beauty by Robert Terry Weston

- A Lover Who Wants His Lovers Near by Rabia

- God Would Kneel Down by St. Francis of Assisi

- How Then Can We Argue? by Meister Eckhart

- Each Soul Completes Me by Hafiz

- This Place of Abundance by St. Catherine of Siena

- First He Looked Confused by Tukaram

- Ode to My Socks by Pablo Neruda

- Summing Up by Claribel Alegria

- If You Have Nothing by Jessica Powers

- Paper Cranes by Thomas Merton

- God Paints the Rainbows by Barb Laski

- A poem about wisdom by Makeda, Queen of Sheba

- In a Holy Book I Have by Hafiz

- Little Things by Sharon Olds

- Joy by Robert Morneau

- The Road to God by Melannie Svoboda

- A poem by Henry Van Dyke

- Chilean Creed by James Conlon

- A poem by Edward Searl

- A poem by Judith Billings

- The Inner History of a Day by John O'Donohue

- A Marriage, an Elegy by Wendell Berry

- The Book of Endings by Sam Taylor

- A poem by Hildegard of Bingen

- Marriage by Susan R. Norton

- A poem by St. John of the Cross

- A poem by J. David Scheyer

- My Life by Billy Collins

- The Foot-Washing by A. R. Ammons

- Simon the Cyrenian Speaks by Countee Cullen

- Early Lynching by Carl Sandburg

- Easter Night by Alice Meynell

- Throw Yourself Like Seed by Miguel de Unamuno

- The Madness of Love by Hadewijch of Antwerp

- Human Wisdom by Charles Peguy

- The Gift by Zoraida Rivera Morales

- A poem by Ly Ngoc Keiu

- Passing Through by Stanley Kunitz

- From Recovery by Rabindranath Tagore

- A poem by Novalis

- Diving by A E I Falconer

- Was it Light? by Theodore Roethke

- The Journey of the Mind by Anya Dunaif

- Looking West by Sofiy Inck

- What Is a Hero? by Nimai Agarwal

- The Word by Swastika Jajoo

- After I Die by Niti Majethia

- True… Or Not? By Swastika Jajoo

- I See The Night by Maya Mesh

- Sowing Hope by Tammata Murthy

- Ever Deeper: A Poem for My Grandfather by Will Hodgkinson

- Blue by Victoria Krylova

- Pure Love by Gertie-Pearl Zwick-Schachter

- When the Universe Sings Goodnight by Niti Majethia

- Plastic Tractors by Will Hodgkinson

- Perfume Bottles by Fareeha Shah

- Rift into Childhood by Gracie Griffin

- When the Sun by Charlotte Rauner

- The Playground in Winter by Maria Christian

- The Soul of Nature by Niti Majethia

- Not Yet by Caie Kelley

- Artemis by Alice Simmons

- The Divine Vision by Tanmaya Murthy

- Backyard Woods by Isabel Bautista

- The Pear Tree by Caroline Harris

- I always feel like myself by Pie Rasor

- Volunteer by Rafik Maharja

- With a Pencil in My Hand by Gracie Griffin

- The Sunset of My Life by Meenu ravi

- The Watching One by Lucia O'Corozine

- Selected Poems from Around the World by Mary Ernesi, Tanika Stewart, and Odelia

- Snowflakes Carry My Worries Away by Katie Champlin

Why Read?

In the clatter and clamor of our lives, we need ways to connect deeply with our souls. Whenever we feel depleted, our favorite poets invariably refresh and refuel us. The quality of their attention, the way they notice things we easily overlook, summons the joy and wonder within us. Their songs of both praise and lament speak the words it is sometimes hard for us to articulate. They put us in the presence of the ineffable and the holy. We drop our jaws and swallow our pride...Businessman James Autry captures another attraction of poetry — it "gives you permission to feel." The best poets tap into our deepest yearnings.

What makes a poem sacred?

A poem is sacred if, after reading it or listening to it, you are just a little wiser and kinder, more creative and playful, more attuned to beauty and shocked by injustice, than you would have been otherwise. The poem makes a difference in how you think and live.

The poem need not be religious in order to be sacred. It does not have to be about God or heavenly ecstasy, or use words like holy and sacred and spiritual. Yes, it can have such themes. It can be obviously religious. But it can also be about ordinary life, about cars and dogs and sidewalks, about whole or broken relationships, about sadness and beauty and moonlight, about planets and tulips and cat's eyes.

Sacredness is a relationship between you and the poem. It lies in how you read the poem and in the fruits of your reading. Here are some of the best fruits of sacred reading, borrowed from Spirituality and Practice.

These fruits are practical and ordinary. The sacred becomes fully sacred only when its values are expressed in daily life: at home and in the workplace, among neighbors and strangers, in the parking lot and the schoolyard, in the voting booth and community center. The purpose of sacred poetry is to help you live wisely and compassionately, with love and vitality, in the world beyond poetry. As it achieves its purpose, it simultaneously refreshes and refuels your soul. It gives you permission to feel.

- Jay McDaniel, December 2020

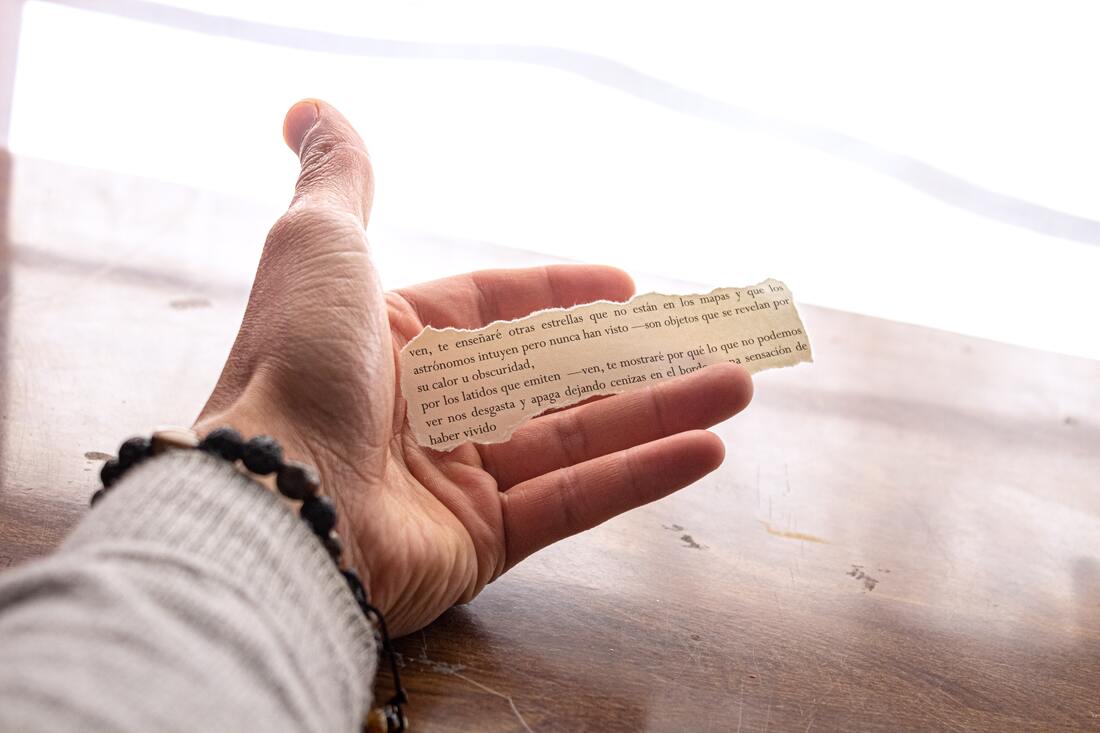

Reading Fragments of Poems

as a Spiritual Practice

Recently some friends of mine started an online poetry journal called Heron Tree. It offers you one poem a week - absolutely free.

As I write this, the poem for the week is Onion Pie by Joey Nicolletti. It begins like this:

The wind, the rattling wall, dinner

baking in the oven, the dead of winter

a string of salt diamonds

alight in a street of slush and starlit ice,

and the cat retires

to his feathery bed.

It is wintertime. I picture my own cat named Zooey, retiring to her own feathery bed. I think of how delicious it would be to have some onion pie. I picture the street outside, which had not long ago been salted with crystals. I remember the diamonds.

I may not read any further. I know that Joey Nicolletti hopes I will. After all, he wrote the poem as an organic whole, with each part related to the other parts. In her now classic The Life of Poetry (1949) Muriel Rukeyser speaks of poems as organic wholes full of movement, which grow like trees. She is famous for saying that the universe is like stories, not atoms. For her a poem is a story, too.

But sometimes I think it's fine just to nibble at a poem, taking a line or series of lines that somehow nourish the imagination and not even completing it. If it's worth reading at all, it's worth reading halfway.

The western religious traditions have a tradition called lectio divina or sacred reading. When you read in a sacred way, you are not looking for rules to live by or ideas to master. You are looking for nourishment of the soul. You take in images from scripture, however fragmentary, and simply rest in them trusting that somehow, in the very resting, some divine nourishment is received. You let the images wash over you and inside you, in a kind of baptism of the imagination.

I need these baptisms. I need one poem a week. I need some onion pie to sink my imagination into, taking a break from the compulsively busy lifestyle into which I so often fall. Buddhists tell us that paying attention to the world around us and the worlds within us in a mindful way is the heart of spirituality. Poetry can help - even if you nibble.

Nibbling

I choose the word nibbling with care. Reading poetry is a physical activity even as it is a spiritual activity. Even if we read silently, we hear our own voice reading inside our heads. We pause at the end of lines and between stanzas, not unlike the way in which we pause when we take a breath. Sometimes we quietly move our lips, too, in a subtle and unconscious way. And sometimes we read out loud. Some people draw sharp distinctions between reading out loud and reading silently. Not me.

As we read we bring our bodies with us. We are sitting or walking, standing or lying down. We are looking with our eyes. The founder of process philosophy, Alfred North Whitehead, says that all of our experiences begin with what he calls the withness of the body. Our bodies are not simply means by which we take our minds from one location to another; they are where the world meets us, including the world of poetry. As we read a poem our minds may be lost in a faraway land, but our bodies are here, with us, in the reading.

Imaginative Nibbling

Of course our imaginations are in the reading, too. Our imaginations enable us to move from one portion of the text to another, not unlike the way in which we might eat fruit salad. When you have a bowl of fruit salad in front of you, you choose the particular fruit -- bananas, strawberries, pineapple-- that strikes your fancy.

I think we can read poems like this, too. By this I mean two things. We do not need to read the whole poem if we are nourished by a part. We can stay with that part, and call it a night.

And even if we do read the whole poem, there is no need to read it in a linear fashion. We can jump from one section to another and then go back, not unlike the way in which we jump from one poem to another in an anthology, flipping back and forth. Call it non-linear nibbling.

Many contemporary poems are conducive to imaginative nibbling. They are a collage of lines which can be strung together in a linear order, forming an organic whole; but they can also be enjoyed in a non-linear way as a collage of fragments which can be seen as a whole but also have independent integrity.

Many sacred scriptures have this quality. Consider the Holy Qur'an. It is a collage of many different poems, and poems within poems, and poems within poems within poems. It is not a rule book, it is a cluster of warnings and invitations, helping us awaken to the unity -- the tawhid - within which we live and move and have our being. Some suras are warnings and some are invitations, but all are inviting us to experience awe and wonder.

Many poems are like mini-Qur'ans. This means that as you read them you can move from beginning to end; but you can also move from middle to beginning or from end to middle. And you can just stay on one or two lines if you are so inclined. You can begin in the middle, where all beginnings begin.

Beginning in the Middle

Think of how people read the Bible. There is no commandment in the Bible which says: "Thou shalt never begin in the middle." Jews and Christians begin in the middle all the time, turning to this book and that book within the good book. And for process thinkers, influenced by Whitehead, there may even be some divine sanction in it. According to process theology, the universe is without beginning or end. God does not create out of nothing but rather out of the pre-existing chaos at hand. This means that even the Holy One began in the middle when he or she began creating our universe. The chaos already existed. The Holy was just giving it a little order. If God can begin in the middle, we can, too. Let the winds of the spirit blow where they will.

For my part, when I begin in the middle, I always look for sentences that do not begin with "The." There is far too much declaration in the world today. Too many attempts to tidy things up, when there's so much beauty in the untidy. Too many ideologies of heart and mind. Buddhists teach us that there is a lot of spirituality in not having fixed views.

Kissed by Steam

There is a Zen rock garden in Kyoto that's designed so that, wherever you stand, you cannot see the whole. You see sand and the rocks, but no possibility for a controlling overview. All good poems are like this. Even if they come across as organic wholes, there's no final interpretation. Freedom from finality of statement is one of poetry's greatest gifts to humanity.

This is why it can be important -- even spiritually enlightened -- to focus on fragments. You are reminding yourself that even if you read the poem as a whole, this whole is nested in a larger whole -- the forever fluid rock garden of the universe -- which is never fully encompassed by any finite observer. Heidegger reminds us that we are always already inside this whole, and that we can never stand outside it and pretend that we are mere spectators.

When a simple line or phrase in the middle of a poem becomes the subject of your attention, you are aware of an immediate textual background that you don't know and comprehend. You are deciding not to know this background, at least for the moment.

This deciding not to know the whole is an act of faith. It is faith that there can be meaning in the particular which transcends the meaning of the whole, even as there is meaning in the whole which transcends the meaning of the particular. Here are the last two lines of Joey Nicolletti's poem:

my wife pulls the Onion Pie

out of the oven, kissed by steam.

Blake reminds us to see heaven in a wildflower and the universe in a grain of sand.

Onion Pie reminds us that there's more than a little divine steam when you take an onion pie out of the oven on a cold, cold day.

Maybe that is one of the purposes of poetry at its best. Maybe it helps us become kissed by the steam.

- Jay McDaniel, December 2020

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)