Questions Atheists ask of God, Religion,

the Church, and Christianity itself

by R.E. Slater

April 22, 2022

Here at Relevancy22 I try to listen and consider all approaches to things metaphysical, ontological, epistemological, ethical, and especially religious... in the Christian sense... as that is what I am familiar with and was raised within from my earliest days of childhood upwards.

It may surprise a few of my fundamental, or evangelical, readers that I still claim God as real; Jesus as my Savior; Love as God's modus operandi (not hell, wrath, and judgment as I was taught); that we have a capacity as humans for both good and evil; and that the future is not closed, but open, hopeful, optimistic (rather than a thing to be dreaded), and moves according to its inherent DNA.

Over the years all of these subjects I have at one time or another addressed... perhaps not as a fundamentalist would, or even as an evangelic any longer.. but perhaps as a post-evangelic, process theologian might... or as near to it as I can understand its ramifications for Christianity (as well as that of other religions). Further, those subjects themselves have also been reframed over the years as I move out of my rigid past and into my speculation of philosophic theology. Good theologians must do this or they can no longer stay relevant with their readers and contemporary times.

Mostly, I've tried to answer the deep questions of life, of religion, of spirituality, in unique ways to how I was educated and trained to answer those same questions from my deeply conservative and Baptistic faith traditions. I ask questions like:

- How did the Church Fathers get to their ideas expressed in the Christian Church's Confessional Creeds and Dogmas?

- How did Greek philosophy usurp the Old Testament Hebraic underpinnings of the even more ancient *Semitic philosophies? (*relating to, or denoting, a family of languages which includes Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic and other ancient languages such as Phoenician and Akkadian, constituting the main subgroup of the Afro-Asiatic family.)

- Or rather, how did Greek philosophy end up guiding all parts of the bible, both in the Old as well as in the New Testament? And importantly, in the Church's Christian expression of its faith?

- How has religious man - whether in really ancient societies, or the cultures in Jesus's day, or the many eras afterwards to this present moment - determine Christianity's "systematized" doctrines of the bible so knowingly as to reject other, better, teachings of the Judaic and Christian testaments?

- Or why did the Church settle on a variety of systematic theologies canonized through its Catholic and Protestant faiths when in actuality, a biblical theology looks at the flows and patterns of the biblical narrative to help direct towards the bare minimums of the Christian faith without locking down its studied beliefs? Which is another way of saying, when studying one's faith, try to avoid unloving expressions of God and creation.

Of course, my list can go on and on and on... as can yours if sit down and think about all the absurdities of proposed Christian beliefs found within certain denominational or sectarian tenet directives of the more popular church testimonies to God, Christ, the Bible, sin, hell, and eschatological doom.

As a result, in redress of all of my inherited tradition's assured Christian beliefs I could no longer hold to them any longer. In fact, the Lord removed me for nearly a year to walk through a wilderness of doubt and uncertainty to prepare my heart, mind, and soul (a Greek reductionistic ideation; Hebraic is expressed more organically as one's soul) to return to the present day and rewrite, recategorize, rethink, and redesign how a Loving, Learning, Healing, Redeeming Christianity might actually look at life if removed from the ancient Church Father's writings, their Creeds and Confessions, or the many bright Church illuminaries who continue on to this day adding such newer ponderous doctrines of Christian apologia to the Church's Creeds such as the inerrancy, infallibility, and authority of the Scriptures for faith and practice. In essence, it is how Evangelicalism has decided to claim for itself the rightness of its beliefs by going to the very same Scriptures I do not find inerrant, infallible, nor authoritative (if by this latter I am not allowed to question the church's declaration of its legalized beliefs).

In sum, I have cauterized and replaced bad Christian teachings with better speculations, ideations, conceptualizations, and perhaps, a more holistic, organic philosophic-theology more akin to the older Semitic cultures of yesteryear without dismissing the present day's discussions in academia, science, and all other disciplines.

I cannot say that I have accomplished this fully, but I did wish to set a precedence of questioning the unquestionable, and by listening and considering the unsanctioned. It seems to my heart that God is truer to what a God should be - and how this God would be communicating to us - than simply closing down discussions based upon ancient, errant narratives of people and cultures who were similarly attempting to tell of their belief in God while chained to their own older, more beautiful-and-awful ideas of God.

At least this is my preferred approach to reading Scripture, reading society, and myself. It's all open and we have good beginnings in many areas but also many more questions too.

I can no longer read the Bible with a capital "B" but with a small "b" bible, reminding myself that the narratival thoughts and expressions of God found throughout it's many era-specific religious beliefs were more like what other individuals and communities have been working through when trying to speak of God to themselves and their neighbors.

In those narratives and voices found both in Scripture as well as in Scriptural writings, as many good, as well as, as many horrible things have been done in the name of God. Which is not unlike today's Trumpian churches mixing White Christian Nationalism, God, Guns, and Jesus into the politicized Republican GOP platforms, no less than they had been in the very earliest expressions of traditionalized church teachings through the centuries.

Moreover, I can no longer simply read of Church doctrines as unpliable and unquestioned definitions of my Christian faith when such teachings and dogmas have been hammered down as inflexible set expressions codified into strict, legal-and-religious, teachings forever removed from nullifiable future commentary.

The commentary spent here at Relevancy22 intends to question, rip apart, destroy, and reform wretched Christian beliefs so that it might better resonate with a God intimately present and in love with creation as versus a God infinitely removed from us, condemning us for being who He made us to be, and consigning all to a hellish fire of damnation unless we submit to some form of religious formulae to save our souls.

Hence, to those atheists, agnostics, and ex-Christians, who have given up on the formalized church... to the nonreligious, the unquestioning, and spiritualists amongst us, I hear you... as do my other fellow Christian writers and theologs who themselves have also undergone the same fiery transformative process I have been going through myself. After editing and writing 2500+ articles I can only say I like where Relational Process Christianity is taking me at the guidance of the Holy Spirit who has spoken to other like-minded individuals saying to His Church, "Enough, let's do this again, and let's do it better, if possible."

|

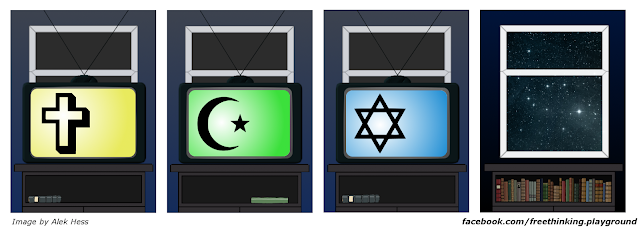

My response is "to listen"... they have legitimate questions

to be considered and addressed. |

Below are the questions a handful of atheists are asking of Christianity. I do sympathize with their perspectives; do believe their questions can find better answers than are found within evangelical Christianity; and would like to challenge them, as I have myself, how we might together answer the questions of God based upon what we have learned from history, literature, academia, and today's matriculating postmodern, and metamodern, philosophies and theologies.

As a Christian I would like to take into my religious background and education the ability to challenge my faith's precepts and teachings with better questions - not better defenses (apologias).

And with a Richard Rohr-like contentedness, to sit still in the question of faith in order to speculate through listening without the demand for immediate answers.

And finally, to utilize the sacred cloistered hallways of doubt and uncertainty to lead us into a fuller faith journey than the one we've be taught that through these experiences we may come to know Jesus, our Redeemer and Living Lord.

Peace,

R.E. Slater

April 22, 2022

* * * * * * *

Why, as an atheist, I’m worried about

the declining interest in religious studies

by Alex J. O'Conner

23 May 2019

The opium of the people; a universal and obsessional neurosis; a means of exerting control over those who can’t handle their freedom; even the most strident of iconoclasts appearing on the theology syllabus, from Karl Marx to Ivan Karamazov, are invariably forced to admit that the object of their criticism is an expression of something deeply human, and a profoundly fundamental component of social behaviour. Yet despite religion’s intellectual preeminence, its study is in steep decline, and this emptying of classrooms and lecture halls is something even a non-believer like myself can be troubled by.

When I applied to study philosophy and theology at St John’s College, Oxford, it was out of necessity; this university, unlike most others, including Cambridge, does not offer an undergraduate course in philosophy alone, so those who wish to study it have to pair it with something else. Theology wasn’t the most appealing of options available; I would rather say it was the least unappealing, and I was content to put up with the headaches and frustrations of reading it as an atheist in order to spend my remaining time with Hume and Mill and Singer. Before long, however, I began to realise that a degree in theology is not suitable only for the religious, and, to my surprise, to rather enjoy it.

Part of the reason for this turnaround is that at Oxford we don’t do theology; we do theology and religion. Studying a paper on the figure of Jesus, I remember being surprised by my tutor’s eager willingness to allow me to skip his suggested reading of Edward Schillebeeckx, the Belgian Catholic theologian whose influence is scattered across Vatican II’s theological constitutions, in favour of Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche, both men not quite as charitable to Holy Mother Church as Mr. Schillebeeckx in their contributions to discussions of Catholicism (and both men whose writings I was far more enthusiastic about spending some time with my nose in). I was struck by a sense of academic freedom that has since characterised my study of religion, and by an emerging sense within me that this ‘lesser’ half of my degree may well contain a wealth of secular - even critical - value.

Through my engagements with both the received wisdom of a variety of theological schools and proposed explanations as to why people subscribe to them, I have repeatedly encountered arguments just as relevant to the most pressing issues of modern society as to the religious context of their original publication.

Does the anthropological observation that religion arose independently in isolated tribes indicate a human tendency to invent figures of unassailable authority? If so, is this the same tendency that leaves us so susceptible to promises of worldly authority at the expense of liberty? The latter issue is of obvious importance in an age of digitised personal information and global military expediency. Does it indicate a human tendency towards tribalism and shared identity based in supernatural beliefs? This is surely a crucial component to any explanation of modern populism. If religion can, as it must, help those who study it to understand the nature and core of humanity’s most cherished and universal convictions, how could this not be of relevance to the modern statesman, philosopher or social scientist?

Walking past the iconic university buildings of Oxford, one of the oldest of which was erected specifically to service the school of divinity, towards the uncharacteristically bland theology faculty building that now serves as the home to this dying subject, is depressing.

I would like to optimistically suggest that the neglect of religious studies at Oxford is due to a simple decline in interest from potential undergraduates in the subject, however I am more inclined to believe that it is in fact due to a decline in understanding of what its study really entails. The queen of the sciences has lost her crown, and it is unclear whether she will ever find it again. If she does, however, it will not be due to an increase in the popularity of religion, but rather an increase in the recognition of the worth of its analysis and study, which is undeniable.

*Alex J O'Connor is a philosophy and theology student at Oxford University. Follow him on Twitter @cosmicskeptic

* * * * * * *

DISGUSTING Things From My Theology Degree

Jul 15, 2019

--------------------------------------VIDEO NOTES--------------------------------------

Having just finished my first year studying philosophy and theology at Oxford University, I decided to compile some of the ideas of two key thinkers from the syllabus that I find troubling.

--------------------------------------------LINKS---------------------------------------------

* * * * * * *

I’m currently reading Philosophy and Theology at Oxford University, and have decided to share the reading lists that I’m set as I receive them from my tutors. At the time of writing, I have completed my first term of my first year of study, so this list will expand as I progress through my degree.

In the first term, I studied one paper (Logic and Moral Philosophy) for philosophy, and one paper (Religion and Religions) for theology. Logic is formal logic taught from a single textbook over eight weeks; Moral Philosophy is an in-depth, term-long study of a single text, J.S. Mill’s Utilitarianism; Religion and Religions is the study of religion as a human phenomenon through a psychological, anthropological and sociological lens, as well as a study of four major world religions.

Next term, I will study for two papers: General Philosophy (for philosophy) and The Figure Of Jesus Through The Centuries (for theology). I will update this list when I have competed the term.

I will try to break down the reading as clearly as possible.

(Please note that the majority of set reading at university is for particular chapters and passages, which I have tried to denote in this list. Books that have already been mentioned previously in the list (but for different chapters) are denoted with an asterisk (*). Also, not all the books that were set did I read, and not all the books I read were set; I have added a few books to the sociology of religion section.)

Year One Philosophy

Logic

- The Logic Manual, by Volker Halbach

Moral Philosophy (Utilitarianism)

General/Reference

- Utilitarianism, by J.S. Mill

- Mill on Utilitarianism, by R. Crisp

- Cambridge Companion to Mill, by J. Skorupski

- John Stuart Mill, by J. Skorupski

Weeks 1-2: Utility and Desire

Reasons and Persons, by D. Parfit, Reasons and Persons, (Appendix I)

Ethics, by J.L. Mackie (ch.6, especially sections 6 and 7)

Well-Being, by J. Griffin (chs. 1-3)

Weeks 3-4: The Proof of Utilitarianism

Weeks 5-6: The Forms of Utilitarianism

*Utilitarianism, by J.S. Mill (especially chs. 2 and 5)

*Mill on Utilitarianism, by R. Crisp (ch. 5)

Moral Thinking, by R.M Hare (chs. 2-3)

Utilitarianism For and Against, by Smart and Williams (esp. sect. 7 of Smart and sect. 6 of Williams)

Ideal Code, Real World, by B. Hooker (chs. 1, 3, and 4)

Consequentialism and Its Critics, by S. Scheffler (introduction)

Weeks 7-8: Justice and Equality

*Utilitarianism, by J.S. Mill (ch .5)

*Mill on Utilitarianism, by R. Crisp (ch. 7)

Anarchy, State and Utopia, by R. Nozick (chs. 2 and 7)

‘Rights as Trumps’ by R. Dworkin in Theories of Rights, by J. Waldron

“Are There Any Natural Rights?”, by H.L.A Hart in Philosophical Review 64 (1955)

Year One Theology

Religion and Religions

General (Introductory)

- Get Set for Religious Studies, by D. Corrywright and P. Morgan

- Religion: The Modern Theories, by S.D. Kunin

- Religion: The Classical Theories, by J. Thrower

- Religions in the Modern World, by L. Woodhead

- Nine Theories of Religion, by D. Pals

- Comparative Religion: A History, by E. Sharpe

Classical Texts

- From Primitives to Zen; A Thematic Sourcebook of the History of Religions, by M. Eliade

- The Golden Bough, by J.G. Frazer

- The Varieties of Religious Experience, by W. James

- The Idea of the Holy, by R. Otto

- Speeches on Religion, by F. Schleiermacher

- The Rites of Passage, by A. van Gennep

Other General Suggestions

- The Anthropology of Religion, by F. Bowie

- The Meaning and End of Religion, by W. Cantwell Smith

- Religion Defined and Explained, by Clarke and Byrne

- The Sacred and the Profane, by M. Eliade

- Theories of Primitive Religion, by E. Evans-Pritchard

- The New Penguin Handbook of Living Religions, by J. Hinnells

- The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion, by J. Hinnells

- The World’s Religions, by N. Smart

Week One: What Is Religion?

- *Religion Defined and Explained, by Clarke and Byrne

- *Theories of Primitive Religion, by E. Evans-Pritchard

- *Religion: The Classical Theories, by J. Thrower

Week Two: Is Studying Religion Doing Theology?

- Understanding Religion, by E. Sharpe

- Approaches to the Study of Religion, by P. Connolly (ch. 7 by F. Whaling)

- The Study of Religion, Traditional and New Religions, by Sutherland and Clarke

- Theology: A Very Short Introduction, by D. Ford

Week Three: The Idea Of The Holy

- The Idea of The Holy, by R. Otto

- *Religion: The Modern Theories, by S.D. Kunin (ch. 5)

- *Comparative Religion: A History, by E. Sharpe (particularly ch. 7)

Week Four: The Sociology Of Religion

- *Nine Theories of Religion, by D. Pals (chapters on Durkheim, Marx, and Weber)

- *The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion, by J. Hinnells (chapter on sociology)

- The Sociology of Religion, by M. Hamilton

- The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, by E. Durkheim

- The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, by M. Weber

- Sociology of Religion, by M. Weber

- Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, K. Marx (introduction)

Week Five: Islam

- Islam: A Very Short Introduction, by M. Ruthven

- Discovering Islam, by A. Ahmed

- Islam: The Straight Path, by J. Esposito

- Muhammed, by M. Rodinson

Week Six: Hinduism

- Hinduism: A Very Short Introduction, by K. Knott

- Hinduism: A Short History, by K. Klostermaier

- Hinduism and Modernity, by D. Smith

- The Hindu View of Life, by S. Radhakrishnan

We did not have tutorial on Judaism or Buddhism, but were still given the reading for Judaism:

Judaism

- Judaism: A Very Short Introduction, by N. Solomon

- The Jewish Heritage, by D. Cohn-Sherbok

- Modern Judaism, by D. Cohn-Sherbok

- The Essence of Judaism, by L. Baeck