Hilary Putnam, American Philosopher

by Yemima Ben-Menahem

Barbara Druss Dibner Professor of the History of Science Emeritus,

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Author of Conventionalism and others.

Last Updated: Mar 10, 2021

Hilary Putnam, (born July 31, 1926, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.—died March 13, 2016), leading American philosopher who made major contributions to metaphysics, epistemology, the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of language, the philosophy of science, the philosophy of mathematics, and the philosophy of logic. He is best known for his semantic externalism, according to which linguistic meanings are not purely mental entities but reach out to external reality; his antireductionist philosophy of mind; and his persistent defense of realism, the view that truth and knowledge are objective. In his later years he became increasingly sensitive to the moral aspects of epistemology and metaphysics and, more generally, to philosophy’s moral calling.

Early Life And Career

Putnam was the only child of Samuel and Riva Putnam. His father was a writer and translator, an active communist, and a columnist for the Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). Putnam studied mathematics and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania and attended graduate school in philosophy at Harvard University and the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). At UCLA he wrote a dissertation, under Hans Reichenbach, on the concept of probability, obtaining a Ph.D. in 1951. He taught philosophy at Northwestern University, Princeton University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) until 1976, when he joined the philosophy department at Harvard. He retired as Cogan University Professor Emeritus at Harvard in 2000.

At Princeton, where he became acquainted with the logical positivist Rudolf Carnap and the mathematical logician Georg Kreisel, Putnam immersed himself in mathematical logic. Among other projects, he worked on one of the 23 unsolved problems in mathematics identified by David Hilbert in 1900: that of finding a general algorithm for solving Diophantine equations (polynomial equations, named after Diophantus of Alexandria, involving only integer constants and allowing only integer solutions). The basis for a proof that the problem is unsolvable was provided by Putnam, Martin Davis, and Julia Robinson in 1961 and completed by Yuri Matiyasevich in 1970.

During the 1960s Putnam was deeply involved in the antiwar movement that opposed U.S. participation in the Vietnam War. He was active in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and in the Progressive Labor Party, a Maoist group, but by the early 1970s he had become disillusioned with far-left political ideology. At about the same time, he developed a sustained interest, both personal and professional, in his Jewish heritage.

Realism And Meaning

The unifying theme of Putnam’s philosophy is his defense of realism, the view that, ordinarily, assertions (including theories, beliefs, and so on) are objectively true or false. Putnam, like most realists, also upheld the possibility of knowledge, distinguishing between knowledge and mere belief, convention, dogma, and superstition. Always self-reflective and self-critical, Putnam frequently revisited and revised his earlier positions. The most-pronounced change occurred in 1976, when he launched an attack on the view he called “metaphysical realism,” recommending that “internal realism” be adopted in its stead (see below Varieties of realism). Internal realism, in turn, was also modified. Over the years, however, it became exceedingly clear that Putnam’s commitment to realism overrode the nuanced differences between the various versions of realism he espoused. The clearest indication of this core stability is the centrality of his theory of meaning to all his versions of realism.

Questions about the nature of truth and objectivity have always occupied a central place in philosophy. Following the “linguistic turn” in Anglo-American (analytic) philosophy in the early 20th century, these questions came to be inseparable from questions about linguistic meaning and representation. An account of the word-world relation (the relation between words and the things in the world they refer to or represent) is thus considered fundamental to contemporary philosophy. For instance, it is crucial for philosophers to take a position on the question of whether there is a uniquely correct representation of the world in language or whether multiple languages represent the world in diverse and possibly incompatible ways, all equally legitimate. Moreover, truth and meaning are closely linked. To determine whether a certain sentence is true, one must be able to understand the sentence, to know what it means. On the other hand, it stands to reason that understanding a sentence involves knowing under what conditions it should be considered true (or false). Theories of truth and meaning are thus inherently interconnected. This connection is manifest in Putnam’s conception of meaning, first proposed in his classic paper “The Meaning of ‘Meaning’ ” (1975), which construes meanings not as purely mental entities (e.g., mental images) or as purely conceptual constructs but as being anchored in external reality. This conception, known as semantic externalism, can therefore serve as a basis for an objective account of truth and knowledge. Consequently, it can also support realism—and was indeed employed by Putnam (and many others after him) to that end.

Putnam’s early defense of realism was primarily directed against the logical positivists, who held a verificationist theory of meaning. According to this theory, synthetic statements—statements that are not true, or false, merely by virtue of the meanings of their terms (“All bachelors are unmarried”)—are cognitively meaningful only if they are empirically verifiable, at least in principle. Logical positivists claimed that value judgments, inasmuch as they express emotional attitudes that are, by their very nature, subjective, have no truth value (i.e., are neither true nor false) and are devoid of cognitive meaning. They further claimed that the theoretical (as opposed to the observational) claims of science are also unverifiable and in fact function as predictive instruments (predictors of observations) rather than as descriptions of an independently existing reality. Against the logical positivists, Putnam argued that the verificationist view of scientific theories rendered the overwhelming success of science a miracle. In other words, if successful scientific theories are not understood as describing an independently existing reality, their success is impossible to explain. This argument for realism came to be known as the “no-miracle” argument for realism. Putnam was equally critical of conventionalism, the view that logic, mathematics, and extensive portions of science do not express truths but are based on human stipulations—i.e., convention.

It soon became apparent, however, that the most serious threat to realism was not verificationism or conventionalism but metaphysical relativism, a clear model of which was provided by the American philosopher of science Thomas S. Kuhn in his influential work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). According to Kuhn, different stages in the history of scientific thought are characterized by different scientific paradigms, or worldviews, each consisting of a body of formal theories, classic experiments, and trusted methodologies. Because the theories of a given paradigm will refer to entities that have no exact, if any, parallel in other paradigms, theories falling under different paradigms refer—literally—to different worlds and are therefore “incommensurable”: they can be neither compared with each other nor tested against some putative objective reality. In essence, the notion of reality is discarded.

The theory of meaning underlying this relativist picture is that meanings are constituted “internally” within each paradigm. Theoretical changes generate changes in the meanings of scientific terms (i.e., the terms are associated with different definitions or descriptions), which in turn lead to changes in reference (i.e., the terms are taken to refer to different entities). In short, meaning is relative to a theory, paradigm, or conceptual scheme. Moreover, truth is also relative in this sense, in virtue of the close connection between truth and meaning: if the meaning of a theoretical statement is relative to a theory, paradigm, or conceptual scheme, then its truth value will be relative in the same way and to the same extent.

If this theory of meaning is accepted—i.e., if typical scientific terms have different meanings, and thus different referents, in different paradigms—then theories grounded in different paradigms are indeed incommensurable. Even worse, they lose contact with reality. From the realist point of view, these conclusions are totally unacceptable. Yet as long as the theory of meaning from which they follow is accepted, they cannot simply be dismissed. To defend realism against this kind of relativism, therefore, an alternative theory of meaning is required.

Putnam rose to this challenge, proposing a theory that, among other things, rejected the common assumption that meanings are mental entities (e.g., beliefs or mental images). “Meanings just ain’t in the head!” as he put it in “The Meaning of ‘Meaning.’ ” Nor are meanings constituted by definitions or descriptions. Rather, it is reference (or extension)—the entity one points to when introducing or explaining a term—that is paramount in fixing meaning and determining whether words vary in meaning from speaker to speaker or from theory to theory. Although reference does not exhaust meaning, it constitutes its essential core. The same referent may thus be characterized in different ways in different theories, so that the theories may vary while their referents remain fixed. This move enabled Putnam to put forward two claims that, taken together, defeat the relativist argument:

1. Theories grounded in different paradigms can refer to the same entities. The connection between a scientific term and the entity to which it refers is established by causal chains of prior uses of the term and by social practices such as pointing, moving, and weighing, rather than by definitions, descriptions, or mental images. This claim rebuts the incommensurability argument.

2. Different speakers can associate a word with identical beliefs and mental images, or even with the same definition, and yet diverge in the meanings they ascribe to it. Putnam devised his “Twin Earth” thought experiment to demonstrate this claim. Twin Earth replicates Earth in almost every detail, including its inhabitants, who are exact duplicates of the inhabitants of Earth, speaking the same languages and having the same mental lives (e.g., the same beliefs and mental images). On Twin Earth, however, the stuff that looks, feels, and functions like water on Earth is not H2O but a different chemical compound, abbreviated XYZ. (Because the year is 1750—about 50 years before the molecular structure of water was discovered—the inhabitants of Earth and Twin Earth do not know that the substances they call “water” are H2O and XYZ, respectively.) Although the beliefs and images associated with the word water on Twin Earth are identical to those associated with water on Earth (e.g., the inhabitants of both planets believe that “water is the clear liquid that fills the oceans, lakes, and rivers and falls as rain”), the term differs in meaning on the two planets because the substance it refers to on Earth differs from the substance it refers to on Twin Earth. The word water, Putnam argues, always refers to the stuff “out there” in the external world that a speaker, uttering “water,” might point to when identifying or referring to a certain liquid as water. From an Earthly perspective, the word water always refers to the stuff that an Earthling might point to, whereas on Twin Earth it refers to the stuff that a Twin Earthling might point to. This conclusion is a manifestation of the externalism that is at the heart of Putnam’s conception of meaning.

Another aspect of Putnam’s theory of meaning is what he called “the division of linguistic labor”—namely, the fact that lay users of a language need not have the detailed knowledge of it that experts have. For example, as long as there are, in the community of speakers, experts who know how to tell gold from other materials, lay speakers can successfully use the term gold to refer to that substance even though they lack the knowledge in question. This view, originally articulated in “The Meaning of ‘Meaning,’ ” was later elaborated on to highlight further features of linguistic practice, the most important being context-dependence, or the variation of meaning with speaker background and conversational context. Thus, words such as honour and justice may have very dissimilar meanings in different cultures, and even scientific terms such as atom and heat can vary with time and context.

Varieties Of Realism

Beginning in the mid-1970s, Putnam sought to distinguish his understanding of realism from what he now called “metaphysical realism.” According to Putnam (“Why There Isn’t a Ready-Made World” [1983]),

What the metaphysical realist holds is that we can think and talk about things as they are, independently of our minds, and that we can do this by virtue of a “correspondence” relation between the terms in our language and some sorts of mind-independent entities.

For Putnam, this picture of word-world correspondence is absurd, pointing to a realism gone wild. Putnam considered metaphysical realism to be blind to the autonomy and complexity of human language. In particular, it is blind to the fact that the same reality can be described in multiple ways.

Whether Putnam’s early realism was ever “metaphysical” in this sense is questionable, but it is clear that his explicit critique of metaphysical realism gives Putnam’s philosophy a Kantian bent; this is particularly salient in the papers collected in Reason, Truth and History (1981). Much like Kant’s denial of the knowability of the “thing in itself,” the modest realism Putnam endorsed there eschewed the notion of reality “in itself,” with its built-in representation. After initially calling his position “internal realism,” Putnam later referred to it as “commonsense realism” or simply “realism,” as opposed to “Realism.” The essential point is that none of these changes impelled Putnam to deny objective truth. Truth under a description, he maintained, is all the truth one needs to avoid subjectivism and relativism. He emphasized, for example, the prevalence in science and mathematics of the phenomenon of equivalence between different theories or descriptions. Such equivalent theories can differ in their respective ontologies (e.g., one adducing forces, the other fields) and still predict and explain the very same phenomena.

Not surprisingly, this middle ground soon came under fire. Critics considered Putnam’s realism unstable and at risk of collapsing into either metaphysical realism or relativism. The latter option was particularly repugnant to Putnam: in its thoroughgoing denial of objective truth, relativism is but a form of radical skepticism and is clearly at odds with Putnam’s realism.

One of Putnam’s striking insights at that time was that the two polar positions—metaphysical realism on the one hand and skepticism on the other—are equally vulnerable, and for the same reason. Both positions construe truth as radically non-epistemic, and, thus, both countenance the possibility that the best scientific theory of the world—a theory that satisfies every epistemic desideratum and is perfect in every methodological and aesthetic respect—could still turn out to be false. But this possibility, Putnam argued, is meaningless, and so are the metaphysical views that countenance it.

Putnam devoted considerable effort to the rebuttal of skepticism. In particular, he addressed the oft-touted skeptical claim that, for all one knows, one might be a brain in a vat. As Putnam described it in “Brains in a Vat” (1981), this thought experiment contemplates the following scenario:

A human being (you can imagine this to be yourself) has been subjected to an operation by an evil scientist. The person’s brain (your brain) has been removed from the body and placed in a vat of nutrients which keeps the brain alive. The nerve endings have been connected to a super-scientific computer which causes the person whose brain it is to have the illusion that everything is perfectly normal.

The purpose of the thought experiment, Putnam noted, is “to raise the classical problem of scepticism with respect to the external world in a modern way. (How do you know you aren’t in this predicament?)” Here too, Putnam’s argument follows directly from his theory of meaning. On the externalist conception of meaning, words in the vat brain language do not have the same referents as “normal” words in “normal” human languages because they are not causally connected in the normal way to the referents of normal words. In particular, for brains in a vat, the word tree would refer not to real trees but at best to images of trees produced by a supercomputer and experienced by envatted brains. Likewise, the word vat in the vat brain language would refer not to real vats but at best to images of vats so produced and experienced. “In short,” Putnam concluded, “if we are brains in a vat, then ‘We are brains in a vat’ is false.” The brains-in-a-vat hypothesis is thus paradoxical and self-defeating. Skepticism is, it turns out, fundamentally flawed: the skeptic’s concerns cannot even be expressed in a meaningful way.

Putnam’s realism also led him to pursue a realist interpretation of quantum mechanics, a theory generally considered to pose insurmountable difficulties for the realist. Many physicists believe, for example, that quantum mechanics, unlike classical mechanics, does not represent the actual physical state of a system. Rather, it is an algorithm for calculating the probabilities of the results of measurements. Putnam’s first attempt to provide a more realist understanding of quantum mechanics invoked the radical claim that logic is empirical. He argued that quantum mechanics does, in fact, represent real physical states, but the logical rules used for quantum calculations diverge from those used in classical physics. Putnam later renounced that approach, adopting a less radical version of quantum mechanics put forward by David Bohm and further developed by G.C. Girardi, A. Rimini, and T. Weber.

Putnam’s realism also extended to mathematics. Together with the American philosopher W.V.O. Quine, he proposed the indispensability thesis: given that mathematical objects such as numbers, sets, and groups play an indispensable role in the best theories of the world, their reality must be granted (see also philosophy of mathematics: The Fregean argument for Platonism).

* * * * * * * * *

Putnam was known for his willingness to apply equal scrutiny to his own philosophical positions as to those of others, subjecting each position to rigorous analysis until he exposed its flaws.[11] As a result, he acquired a reputation for frequently changing his positions.[12] In philosophy of mind, Putnam is known for his argument against the type-identity of mental and physical states based on his hypothesis of the multiple realizability of the mental, and for the concept of functionalism, an influential theory regarding the mind–body problem.[8][13] In philosophy of language, along with Saul Kripke and others, he developed the causal theory of reference, and formulated an original theory of meaning, introducing the notion of semantic externalism based on a thought experiment called Twin Earth.[14]

In philosophy of mathematics, he and his mentor W. V. O. Quine developed the "Quine–Putnam indispensability thesis", an argument for the reality of mathematical entities,[15] later espousing the view that mathematics is not purely logical, but "quasi-empirical".[16] In epistemology, he is known for his critique of the well-known "brain in a vat" thought experiment. This thought experiment appears to provide a powerful argument for epistemological skepticism, but Putnam challenges its coherence.[17] In metaphysics, he originally espoused a position called metaphysical realism, but eventually became one of its most outspoken critics, first adopting a view he called "internal realism",[18] which he later abandoned. Despite these changes of view, throughout his career he remained committed to scientific realism, roughly the view that mature scientific theories are approximately true descriptions of ways things are.[19]

In the philosophy of perception, Putnam came to endorse direct realism, according to which perceptual experiences directly present one with the external world. He once further held that there are no mental representations, sense data, or other intermediaries that stand between the mind and the world.[20] By 2012, however, he rejected this commitment in favor of "transactionalism", a view that accepts both that perceptual experiences are world-involving transactions, and that these transactions are functionally describable (provided that worldly items and intentional states may be referred to in the specification of the function). Such transactions can further involve qualia.[21][22] In his later work, Putnam became increasingly interested in American pragmatism, Jewish philosophy, and ethics, engaging with a wider array of philosophical traditions. He also displayed an interest in metaphilosophy, seeking to "renew philosophy" from what he identified as narrow and inflated concerns.[23] He was at times a politically controversial figure, especially for his involvement with the Progressive Labor Party in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[24][25] At the time of his death, Putnam was Cogan University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University.

Life

Putnam was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1926. His father, Samuel Putnam, was a scholar of Romance languages, columnist, and translator who wrote for the Daily Worker, a publication of the American Communist Party, from 1936 to 1946 (when he became disillusioned with communism).[26] As a result of his father's commitment to communism, Putnam had a secular upbringing, although his mother, Riva, was Jewish.[11] The family lived in France until 1934, when they returned to the United States, settling in Philadelphia.[11] Putnam attended Central High School; there he met Noam Chomsky, who was a year behind him. The two remained friends—and often intellectual opponents—for the rest of Putnam's life.[27] Putnam studied philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, receiving his B.A. degree and becoming a member of the Philomathean Society, the country's oldest continually existing collegiate literary society.[11][28] He did graduate work in philosophy at Harvard University[11] and later at UCLA'S philosophy department, where he received his Ph.D. in 1951 for his dissertation, The Meaning of the Concept of Probability in Application to Finite Sequences.[29] Putnam's dissertation supervisor Hans Reichenbach was a leading figure in logical positivism, the dominant school of philosophy of the day; one of Putnam's most consistent positions has been his rejection of logical positivism as self-defeating.[28]

After teaching at Northwestern University (1951–52), Princeton University (1953–61), and MIT (1961–65), Putnam moved to Harvard in 1965. His wife, the philosopher Ruth Anna Putnam, took a teaching position in philosophy at Wellesley College.[28] Hilary and Ruth Anna were married on August 11, 1962.[30] Ruth Anna, descendant of a family with a long scholarly tradition in Gotha (her ancestor was the German classical scholar Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Jacobs),[31] was born in Berlin, Germany,[32] in 1927 to anti-Nazi activist parents and, like Putnam, was raised atheist (her mother was Jewish and her father from a Christian background).[33][34][35][36] The Putnams, rebelling against the antisemitism they experienced during their youth, decided to establish a traditional Jewish home for their children.[33] Since they had no experience with the rituals of Judaism, they sought out invitations to other Jews' homes for Seder. They had "no idea how to do it [themselves]", in Ruth Anna's words. They began to study Jewish ritual and Hebrew, and became more Jewishly interested, identified, and active. In 1994, Hilary Putnam celebrated a belated Bar Mitzvah service. His wife had a Bat Mitzvah service four years later.[33]

Putnam was a popular teacher at Harvard. In keeping with his family tradition, he was politically active.[28] In the 1960s and early 1970s, he was an active supporter of the American Civil Rights Movement and opposition to the Vietnam War.[25] In 1963, he organized one of MIT's first faculty and student committees against the war. Putnam was disturbed when he learned from David Halberstam's reports that the U.S. was "defending" South Vietnamese peasants from the Vietcong by poisoning their rice crops.[28] After moving to Harvard in 1965, he organized campus protests and began teaching courses on Marxism. Putnam became an official faculty advisor to the Students for a Democratic Society and in 1968 a member of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP).[28] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1965.[37] After 1968, his political activities centered on the PLP.[25] The Harvard administration considered these activities disruptive and attempted to censure Putnam, but two other faculty members criticized the procedures.[38][39] Putnam permanently severed his ties with the PLP in 1972.[40] In 1997, at a meeting of former draft resistance activists at Boston's Arlington Street Church, he called his involvement with the PLP a mistake. He said he had been impressed at first with the PLP's commitment to alliance-building and its willingness to attempt to organize from within the armed forces.[25]

In 1976, Putnam was elected president of the American Philosophical Association. The next year, he was selected as Walter Beverly Pearson Professor of Mathematical Logic in recognition of his contributions to the philosophy of logic and mathematics.[28] While breaking with his radical past, Putnam never abandoned his belief that academics have a particular social and ethical responsibility toward society. He continued to be forthright and progressive in his political views, as expressed in the articles "How Not to Solve Ethical Problems" (1983) and "Education for Democracy" (1993).[28]

Putnam was a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy. He retired from teaching in June 2000, but as of 2009 continued to give a seminar almost yearly at Tel Aviv University. He also held the Spinoza Chair of Philosophy at the University of Amsterdam in 2001.[41] He was the Cogan University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University and a founding patron of the small liberal arts college Ralston College. His corpus includes five volumes of collected works, seven books, and more than 200 articles. Putnam's renewed interest in Judaism inspired him to publish several books and essays on the topic.[42] With his wife, he co-authored several books and essays on the late-19th-century American pragmatist movement.[28]

For his contributions in philosophy and logic, Putnam was awarded the Rolf Schock Prize in 2011[43] and the Nicholas Rescher Prize for Systematic Philosophy in 2015.[44] He delivered his last Skype talk, "Thought and Language," at an international conference on "The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam" held at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, on October 3, 2015, organized by his student Sanjit Chakraborty.[45][46] Putnam died at his home in Arlington, Massachusetts, on March 13, 2016.[47]

Philosophy of mind

Multiple realizability

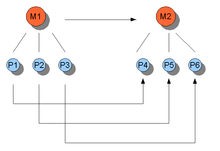

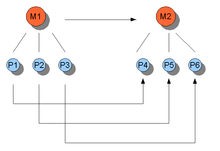

An illustration of multiple realizability.

M stands for mental and

P stands for physical. It can be seen that more than one

P can instantiate one

M, but not vice versa. Causal relations between states are represented by the arrows (

M1 goes to

M2, etc.).

Putnam's best-known work concerns philosophy of mind. His most noted original contributions to that field came in several key papers published in the late 1960s that set out the hypothesis of multiple realizability.[48] In these papers, Putnam argues that, contrary to the famous claim of the type-identity theory, it is not necessarily true that "Pain is identical to C-fibre firing." According to Putnam's papers, pain may correspond to utterly different physical states of the nervous system in different organisms even if they all experience the same mental state of "being in pain".

Putnam cited examples from the animal kingdom to illustrate his thesis. He asked whether it was likely that the brain structures of diverse types of animals realize pain, or other mental states, the same way. If they do not share the same brain structures, they cannot share the same mental states and properties, in which case mental states must be realized by different physical states in different species. Putnam then took his argument a step further, asking about such things as the nervous systems of alien beings, artificially intelligent robots and other silicon-based life forms. These hypothetical entities, he contended, should not be considered incapable of experiencing pain just because they lack human neurochemistry. Putnam concluded that type-identity theorists had been making an "ambitious" and "highly implausible" conjecture that could be disproved by one example of multiple realizability.[49] This is sometimes called the "likelihood argument".[48]

Putnam formulated a complementary argument based on what he called "functional isomorphism". He defined the concept in these terms: "Two systems are functionally isomorphic if 'there is a correspondence between the states of one and the states of the other that preserves functional relations'." In the case of computers, two machines are functionally isomorphic if and only if the sequential relations among states in the first exactly mirror the sequential relations among states in the other. Therefore, a computer made of silicon chips and one made of cogs and wheels can be functionally isomorphic but constitutionally diverse. Functional isomorphism implies multiple realizability.[49] This is sometimes called an "a priori argument".[48]

Putnam, Jerry Fodor, and others argued that, along with being an effective argument against type-identity theories, multiple realizability implies that any low-level explanation of higher-level mental phenomena is insufficiently abstract and general.[49][50][51] Functionalism, which identifies mental kinds with functional kinds that are characterized exclusively in terms of causes and effects, abstracts from the level of microphysics, and therefore seemed to be a better explanation of the relation between mind and body. In fact, there are many functional kinds, such as mousetraps, software and bookshelves, that are multiply realized at the physical level.[49]

Machine state functionalism

Putnam himself put forth the first formulation of such a functionalist theory. This formulation, now called "machine-state functionalism", was inspired by analogies Putnam and others made between the mind and Turing machines. The point for functionalism is the nature of the states of the Turing machine. Each state can be defined in terms of its relations to the other states and to the inputs and outputs, and the details of how it accomplishes what it accomplishes and of its material constitution are completely irrelevant. According to machine-state functionalism, the nature of a mental state is just like the nature of a Turing machine state. Just as "state one" simply is the state in which, given a particular input, such-and-such happens, so being in pain is the state which disposes one to cry "ouch", become distracted, wonder what the cause is, and so forth.[52]

Rejection of functionalism

In the late 1980s, Putnam abandoned his adherence to functionalism and other computational theories of mind. His change of mind was primarily due to the difficulties computational theories have in explaining certain intuitions with respect to the externalism of mental content. This is illustrated by Putnam's own Twin Earth thought experiment (see Philosophy of language).[20] In 1988 he also developed a separate argument against functionalism based on Fodor's generalized version of multiple realizability. Asserting that functionalism is really a watered-down identity theory in which mental kinds are identified with functional kinds, Putnam argued that mental kinds may be multiply realizable over functional kinds. The argument for functionalism is that the same mental state could be implemented by the different states of a universal Turing machine.[53]

Despite Putnam's rejection of functionalism, it has continued to flourish and been developed into numerous versions by Fodor, David Marr, Daniel Dennett, and David Lewis, among others.[54] Functionalism helped lay the foundations for modern cognitive science[54] and is the dominant theory of mind in philosophy today.[55]

By 2012 Putnam accepted a modification of functionalism called "liberal functionalism". The view holds that "what matters for consciousness and for mental properties generally is the right sort of functional capacities and not the particular matter that subserves those capacities".[21] The specification of these capacities may refer to what goes on outside the organism's "brain", may include intentional idioms, and need not describe a capacity to compute something or other.[21]

Philosophy of language

Semantic externalism

One of Putnam's contributions to philosophy of language is his claim that "meaning just ain't in the head". His views on meaning, first laid out in Meaning and Reference (1973), then in The Meaning of "Meaning" (1975), use his "Twin Earth" thought experiment to illustrate that terms' meanings are determined by factors outside the mind.

Twin Earth shows this, according to Putnam, since on Twin Earth everything is identical to Earth, except that its lakes, rivers and oceans are filled with XYZ rather than H2O. Consequently, when an earthling, Fredrick, uses the Earth-English word "water", it has a different meaning from the Twin Earth-English word "water" when used by his physically identical twin, Frodrick, on Twin Earth. Since Fredrick and Frodrick are physically indistinguishable when they utter their respective words, and since their words have different meanings, meaning cannot be determined solely by what is in their heads.[56]:70–75 This led Putnam to adopt a version of semantic externalism with regard to meaning and mental content.[17][49] The philosopher of mind and language Donald Davidson, despite his many differences of opinion with Putnam, wrote that semantic externalism constituted an "anti-subjectivist revolution" in philosophers' way of seeing the world. Since Descartes's time, philosophers had been concerned with proving knowledge from the basis of subjective experience. Thanks to Putnam, Saul Kripke, Tyler Burge and others, Davidson said, philosophy could now take the objective realm for granted and start questioning the alleged "truths" of subjective experience.[57]

Theory of meaning

Along with Kripke, Keith Donnellan, and others, Putnam contributed to what is known as the causal theory of reference.[8] In particular, he maintained in The Meaning of "Meaning" that the objects referred to by natural kind terms—such as "tiger", "water", and "tree"—are the principal elements of the meaning of such terms. There is a linguistic division of labor, analogous to Adam Smith's economic division of labor, according to which such terms have their references fixed by the "experts" in the particular field of science to which the terms belong. So, for example, the reference of the term "lion" is fixed by the community of zoologists, the reference of the term "elm tree" is fixed by the community of botanists, and chemists fix the reference of the term "table salt" as sodium chloride. These referents are considered rigid designators in the Kripkean sense and are disseminated outward to the linguistic community.[49]

Putnam specifies a finite sequence of elements (a vector) for the description of the meaning of every term in the language. Such a vector consists of four components:

- the object to which the term refers, e.g., the object individuated by the chemical formula H2O;

- a set of typical descriptions of the term, referred to as "the stereotype", e.g., "transparent", "colorless", and "hydrating";

- the semantic indicators that place the object into a general category, e.g., "natural kind" and "liquid";

- the syntactic indicators, e.g., "concrete noun" and "mass noun".

Such a "meaning-vector" provides a description of the reference and use of an expression within a particular linguistic community. It provides the conditions for its correct usage and makes it possible to judge whether a single speaker attributes the appropriate meaning to it or whether its use has changed enough to cause a difference in its meaning. According to Putnam, it is legitimate to speak of a change in the meaning of an expression only if the reference of the term, and not its stereotype, has changed. But since no possible algorithm can determine which aspect—the stereotype or the reference—has changed in a particular case, it is necessary to consider the usage of other expressions of the language.[49] Since there is no limit to the number of such expressions to be considered, Putnam embraced a form of semantic holism.[58]

Philosophy of mathematics

Putnam made a significant contribution to philosophy of mathematics in the Quine–Putnam "indispensability argument" for mathematical realism.[59] Stephen Yablo considers this argument one of the most challenging in favor of the existence of abstract mathematical entities, such as numbers and sets.[60] The form of the argument is as follows.

- One must have ontological commitments to all entities that are indispensable to the best scientific theories, and to those entities only (commonly referred to as "all and only").

- Mathematical entities are indispensable to the best scientific theories. Therefore,

- One must have ontological commitments to mathematical entities.[61]

The justification for the first premise is the most controversial. Both Putnam and Quine invoke naturalism to justify the exclusion of all non-scientific entities, and hence to defend the "only" part of "all and only". The assertion that "all" entities postulated in scientific theories, including numbers, should be accepted as real is justified by confirmation holism. Since theories are not confirmed in a piecemeal fashion, but as a whole, there is no justification for excluding any of the entities referred to in well-confirmed theories. This puts the nominalist who wishes to exclude the existence of sets and non-Euclidean geometry but include the existence of quarks and other undetectable entities of physics, for example, in a difficult position.[61]

Putnam holds the view that mathematics, like physics and other empirical sciences, uses both strict logical proofs and "quasi-empirical" methods. For example, Fermat's last theorem states that for no integer  are there positive integer values of x, y, and z such that

are there positive integer values of x, y, and z such that  . Before Andrew Wiles proved this for all

. Before Andrew Wiles proved this for all  in 1995,[62] it had been proved for many values of n. These proofs inspired further research in the area, and formed a quasi-empirical consensus for the theorem. Even though such knowledge is more conjectural than a strictly proved theorem, it was still used in developing other mathematical ideas.[16]

in 1995,[62] it had been proved for many values of n. These proofs inspired further research in the area, and formed a quasi-empirical consensus for the theorem. Even though such knowledge is more conjectural than a strictly proved theorem, it was still used in developing other mathematical ideas.[16]

Mathematics and computer science

Putnam has contributed to scientific fields not directly related to his work in philosophy.[8] As a mathematician, he contributed to the resolution of Hilbert's tenth problem in mathematics. This problem (now known as Matiyasevich's theorem or the MRDP theorem) was settled by Yuri Matiyasevich in 1970, with a proof that relied heavily on previous research by Putnam, Julia Robinson and Martin Davis.[63]

In computability theory, Putnam investigated the structure of the ramified analytical hierarchy, its connection with the constructible hierarchy and its Turing degrees. He showed that there are many levels of the constructible hierarchy that add no subsets of the integers[64] and later, with his student George Boolos, that the first such "non-index" is the ordinal  of ramified analysis[65] (this is the smallest

of ramified analysis[65] (this is the smallest  such that

such that  is a model of full second-order comprehension), and also, together with a separate paper with Richard Boyd (another of Putnam's students) and Gustav Hensel,[66] how the Davis–Mostowski–Kleene hyperarithmetical hierarchy of arithmetical degrees can be naturally extended up to

is a model of full second-order comprehension), and also, together with a separate paper with Richard Boyd (another of Putnam's students) and Gustav Hensel,[66] how the Davis–Mostowski–Kleene hyperarithmetical hierarchy of arithmetical degrees can be naturally extended up to  .

.

In computer science, Putnam is known for the Davis–Putnam algorithm for the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), developed with Martin Davis in 1960.[8] The algorithm finds whether there is a set of true or false values that satisfies a given Boolean expression so that the entire expression becomes true. In 1962, they further refined the algorithm with the help of George Logemann and Donald W. Loveland. It became known as the DPLL algorithm. It is efficient and still forms the basis of most complete SAT solvers.[9]

Epistemology

In epistemology, Putnam is known for his "brain in a vat" thought experiment (a modernized version of Descartes's evil demon hypothesis). The argument is that one cannot coherently suspect that one is a disembodied "brain in a vat" placed there by some "mad scientist".[17]

This follows from the causal theory of reference. Words always refer to the kinds of things they were coined to refer to, the kinds of things their user, or the user's ancestors, experienced. So, if some person, Mary, is a "brain in a vat", whose every experience is received through wiring and other gadgetry created by the mad scientist, then Mary's idea of a brain does not refer to a real brain, since she and her linguistic community have never encountered such a thing. To her a brain is actually an image fed to her through the wiring. Nor does her idea of a vat refer to a real vat. So if, as a brain in a vat, she says, "I'm a brain in a vat", she is actually saying, "I'm a brain-image in a vat-image", which is incoherent. On the other hand, if she is not a brain in a vat, then saying that she is a brain in a vat is still incoherent, because she actually means the opposite. This is a form of epistemological externalism: knowledge or justification depends on factors outside the mind and is not solely determined internally.[17]

Putnam has clarified that his real target in this argument was never skepticism, but metaphysical realism.[67][68] Since realism of this kind assumes the existence of a gap between how one conceives the world and the way the world really is, skeptical scenarios such as this one (or Descartes's evil demon) present a formidable challenge. By arguing that such a scenario is impossible, Putnam attempts to show that this notion of a gap between one's concept of the world and the way it is is absurd. One cannot have a "God's-eye" view of reality. One is limited to one's conceptual schemes, and metaphysical realism is therefore false.[69]

Metaphilosophy and ontology

In the late 1970s and the 1980s, stimulated by results from mathematical logic and by some of Quine's ideas, Putnam abandoned his long-standing defence of metaphysical realism—the view that the categories and structures of the external world are both causally and ontologically independent of the conceptualizations of the human mind. He adopted a rather different view, which he called "internal realism"[70][18] or "pragmatic realism".[71]

Internal realism is the view that, although the world may be causally independent of the human mind, the world's structure—its division into kinds, individuals and categories—is a function of the human mind, and hence the world is not ontologically independent. The general idea is influenced by Immanuel Kant's idea of the dependence of our knowledge of the world on the categories of thought.[72]

The problem with metaphysical realism, according to Putnam, is that it fails to explain the possibility of reference and truth.[73]:331 According to the metaphysical realist, our concepts and categories refer because they match up in some mysterious manner with the categories, kinds and individuals inherent in the external world. But how is it possible that the world "carves up" into certain structures and categories, the mind carves up the world into its own categories and structures, and the two carvings perfectly coincide? The answer must be that the world does not come pre-structured but that the human mind and its conceptual schemes impose structure on it. In Reason, Truth, and History, Putnam identified truth with what he termed "idealized rational acceptability." The theory, which owes something to C. S. Peirce, is that a belief is true if it would be accepted by anyone under ideal epistemic conditions.[18]

Nelson Goodman formulated a similar notion in Fact, Fiction and Forecast (1956). "We have come to think of the actual as one among many possible worlds. We need to repaint that picture. All possible worlds lie within the actual one", Goodman wrote.[74]:57 Putnam rejected this form of social constructivism, but retained the idea that there can be many correct descriptions of reality. None of these descriptions can be scientifically proven to be the "one, true" description of the world. For Putnam, this does not imply relativism, because not all descriptions are equally correct and correctness is not determined subjectively.[75]

Putnam renounced internal realism in his reply to Simon Blackburn in the volume Reading Putnam.[76] The reasons he gave up his "antirealism" are stated in the first three of his replies in "The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam", an issue of the journal Philosophical Topics, where he gives a history of his use(s) of the term "internal realism", and, at more length, in his The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body and World (1999).[77]

Although he abandoned internal realism, Putnam still resisted the idea that any given thing or system of things can be described in exactly one complete and correct way. He thus accepts "conceptual relativity"—the view that it may be a matter of choice or convention, e.g., whether mereological sums exist, or whether spacetime points are individuals or mere limits. In other words, having abandoned internal realism, Putnam came to accept metaphysical realism in the broad sense of rejecting all forms of verificationism and all talk of our "making" the world.[78]

Under the influence of Peirce and William James, Putnam also became convinced that there is no fact–value dichotomy; that is, normative (e.g., ethical and aesthetic) judgments often have a factual basis, while scientific judgments have a normative element.[75]

Neopragmatism and Wittgenstein

At the end of the 1980s, Putnam became increasingly disillusioned with what he perceived as the "scientism" and the rejection of history that characterize modern analytic philosophy. He rejected internal realism because it assumed a "cognitive interface" model of the relation between the mind and the world. Putnam claimed that the very notion of truth would have to be abandoned by a consistent eliminative materialist.[79] Under the increasing influence of James and the pragmatists, he adopted a direct realist view of this relation.[80] For a time, under the influence of Ludwig Wittgenstein, he adopted a pluralist view of philosophy itself and came to view most philosophical problems as nothing more than conceptual or linguistic confusions created by philosophers by using ordinary language out of context.[75] A book of articles on pragmatism by Ruth Anna Putnam and Hilary Putnam, Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey (Harvard UP, ISBN 9780674967502), edited by David Macarthur, was published in 2017.[81]

Many of Putnam's last works addressed the concerns of ordinary people, particularly social problems.[82] For example, he wrote about the nature of democracy, social justice and religion. He also discussed Jürgen Habermas's ideas, and wrote articles influenced by continental philosophy.[28]

Criticism

Putnam himself may be his own most formidable philosophical adversary:[14] his frequent changes of mind have led him to attack his previous positions. But many significant criticisms of his views have come from other philosophers and scientists. For example, multiple realizability has been criticized on the grounds that, if it were true, research and experimentation in the neurosciences would be impossible.[83] According to William Bechtel and Jennifer Mundale, to be able to conduct such research in the neurosciences, universal consistencies must either exist or be assumed to exist in brain structures. It is the similarity (or homology) of brain structures that allows us to generalize across species.[83] If multiple realizability were an empirical fact, results from experiments conducted on one species of animal (or one organism) would not be meaningful when generalized to explain the behavior of another species (or organism of the same species).[84] Jaegwon Kim, David Lewis, Robert Richardson and Patricia Churchland have also criticized metaphysical realism.[85][86][87][88]

Putnam himself formulated one of the main arguments against functionalism: the Twin Earth thought experiment. But there have been other criticisms. John Searle's Chinese room argument (1980) is a direct attack on the claim that thought can be represented as a set of functions. The thought experiment is designed to show that it is possible to mimic intelligent action with a purely functional system, without any interpretation or understanding. Searle describes a situation in which a person who speaks only English is locked in a room with Chinese symbols in baskets and a rule book in English for moving the symbols around. The person is instructed, by people outside the room, to follow the rule book for sending certain symbols out of the room when given certain symbols. The people outside the room speak Chinese and are communicating with the person inside via the Chinese symbols. According to Searle, it would be absurd to claim that the English speaker inside "knows" Chinese based on these syntactic processes alone. This argument attempts to show that systems that operate merely on syntactic processes cannot realize any semantics (meaning) or intentionality (aboutness). Searle thus attacks the idea that thought can be equated with following a set of syntactic rules and concludes that functionalism is an inadequate theory of the mind.[89] Ned Block has advanced several other arguments against functionalism.[90]

Despite the many changes in his other positions, Putnam consistently adhered to semantic holism. Michael Dummett, Jerry Fodor, Ernest Lepore, and others have identified problems with this position. In the first place, they suggest that, if semantic holism is true, it is impossible to understand how a speaker of a language can learn the meaning of an expression in the language. Given the limits of our cognitive abilities, we will never be able to master the whole of the English (or any other) language, even based on the (false) assumption that languages are static and immutable entities. Thus, if one must understand all of a natural language to understand a single word or expression, language learning is simply impossible. Semantic holism also fails to explain how two speakers can mean the same thing when using the same expression, and therefore how any communication is possible between them. Given a sentence P, since Fred and Mary have each mastered different parts of the English language and P is related in different ways to the sentences in each part, P means one thing to Fred and something else to Mary. Moreover, if P derives its meaning from its relations with all the sentences of a language, as soon as the vocabulary of an individual changes by the addition or elimination of a sentence, the totality of relations changes, and therefore also the meaning of P. As this is a common phenomenon, the result is that P has two different meanings in two different moments in the life of the same person. Consequently, if I accept the truth of a sentence and then reject it later on, the meaning of what I rejected and what I accepted are completely different and therefore I cannot change my opinions with regard to the same sentences.[91][92][93]

Putnam's brain in a vat argument has also been criticized.[94] Crispin Wright argues that Putnam's formulation of the brain-in-a-vat scenario is too narrow to refute global skepticism. The possibility that one is a recently disembodied brain in a vat is not undermined by semantic externalism. If a person has lived her entire life outside the vat—speaking the English language and interacting normally with the outside world—prior to her "envatment" by a mad scientist, when she wakes up inside the vat, her words and thoughts (e.g., "tree" and "grass") will still refer to the objects or events in the external world that they referred to before her envatment.[68] In another scenario, a brain in a vat may be hooked up to a supercomputer that randomly generates perceptual experiences. In that case, one's words and thoughts would not refer to anything: semantics would no longer exist and the argument would be meaningless.[95]

In philosophy of mathematics, Stephen Yablo has argued that the Quine–Putnam indispensability thesis does not demonstrate that mathematical entities are truly indispensable. The argumentation is sophisticated, but the upshot is that one can achieve the same logical results by simply adding to any statement about an abstract object the assumption "so-and-so is assumed (or hypothesized) to exist". For example, one can take the argument for indispensability described above and adjust it as follows:

- 1*. One must have ontological commitments to all and only the [abstract] entities for which, under the assumption that they exist, their existence is indispensable to the best scientific theories.

- 2*. Under the assumption that they exist, the existence of mathematical entities is indispensable to the best scientific theories. Therefore,

- 3*. Under the assumption that mathematical entities exist, one must have ontological commitments to the existence of mathematical entities.[60]

Finally, Curtis Brown has criticized Putnam's internal realism as a disguised form of subjective idealism, in which case it is subject to the traditional arguments against that position. In particular, it falls into the trap of solipsism. That is, if existence depends on experience, as subjective idealism maintains, and if one's consciousness ceased to exist, then the rest of the universe would also cease to exist.[72]

Major works and bibliography

Vincent C. Müller compiled a detailed bibliography of Putnam's writings, citing 16 books and 198 articles, published in 1993 in PhilPapers.[96]

- Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Edited with Paul Benacerraf. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1964. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-521-29648-X

- "The 'Innateness Hypothesis' and Explanatory Models in Linguistics", Synthese, Vol. 17, No. 1, March 1967, pp. 12–22.

- Philosophy of Logic. New York: Harper & Row, 1971. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1972. ISBN 0-04-160009-6

- Mathematics, Matter and Method. Philosophical Papers, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. 2nd. ed., 1985 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29550-5

- Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. 2003 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29551-3

- Meaning and the Moral Sciences. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978.

- Reason, Truth, and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981. 2004 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29776-1

- Realism and Reason. Philosophical Papers, vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. 2002 paperback: ISBN 0-521-31394-5

- Methodology, Epistemology, and Philosophy of Science: Essays in Honour of Wolfgang Stegmüller. edited with Wilhelm K. Essler and Carl G. Hempel. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1983.

- Epistemology, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science: Essays in Honour of Carl G. Hempel. edited with Wilhelm K. Essler and Wolfgang Stegmüller. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1985.

- The Many Faces of Realism. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court, 1987. ISBN 0-8126-9043-5

- Representation and Reality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1988. ISBN 0-262-66074-1

- Realism with a Human Face. edited by J. F. Conant. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1990. 9780674749450 Description. ISBN 0-674-74945-6

- Renewing Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992. 9780674760943 Description. ISBN 0-674-76094-8

- Pursuits of Reason: Essays in Honor of Stanley Cavell. edited with Ted Cohen and Paul Guyer. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-89672-266-X

- Words and Life. edited by J. F. Conant. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1994. 9780674956070 Description. ISBN 0-674-95607-9

- Pragmatism: An Open Question. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995. ISBN 0-631-19343-X

- The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-231-10287-9

- Enlightenment and Pragmatism. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum, 2001. 48pp.

- The Collapse of the Fact/Value Dichotomy and Other Essays. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002. Description. ISBN 0-674-01380-8

- Ethics Without Ontology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002. 9780674018518 Description. ISBN 0-674-01851-6

- Jewish Philosophy as a Guide to Life: Rosenzweig, Buber, Levinas, Wittgenstein. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

- Philosophy in an Age of Science, edited by Mario De Caro and David Macarthur. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2012. 9780674050136 Description.

- Naturalism, Realism, and Normativity, edited by Mario De Caro, Cam, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2016, ISBN 9780674659698.

- Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey (with Ruth Anna Putnam), edited by David Macarthur, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2017. Description. ISBN 0-674-96750-X.

See also

Notes

- ^ Pragmatism – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Hilary Putnam, "Realism and reason", Presidential Address to the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association, December 1976; reprinted in his Meaning and the Moral Sciences, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978, pp. 123–140.

- ^ Bas van Fraassen, "Putnam's Paradox: Metaphysical Realism Revamped and Evaded", Philosophical Perspectives 11:17–42 (1997).

- ^ David Marshall Miller, Representing Space in the Scientific Revolution, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 4 n. 2.

- ^ Hilary Putnam. Realism with a Human Face. Edited by James F. Conant. Harvard University Press. 1992. p. xlv.

- ^ Borradori, G. et al. The American Philosopher, 1994, p. 58

- ^ J. Worrall, "Structural Realism: the Best of Both Worlds" in D. Papineau(ed.), The Philosophy of Science (Oxford 1996).

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Casati R., "Hillary Putnam" in Enciclopedia Garzanti della Filosofia, ed. Gianni Vattimo. 2004. Garzanti Editori. Milan. ISBN 88-11-50515-1

- ^ Jump up to:a b Davis, M. and Putnam, H. "A computing procedure for quantification theory" in Journal of the ACM, 7:201–215, 1960.

- ^ Matiyesavic, Yuri (1993). Hilbert's Tenth Problem. Cambridge: MIT. ISBN 0-262-13295-8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e King, P.J. One Hundred Philosophers: The Life and Work of the World's Greatest Thinkers. Barron's 2004, p. 170.

- ^ Jack Ritchie (June 2002). "TPM: Philosopher of the Month". Archived from the original on 2011-07-09.

- ^ LeDoux, J. (2002). The Synaptic Self; How Our Brains Become Who We Are. New York: Viking Penguin. ISBN 88-7078-795-8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b P. Clark-B. Hale (eds.), "Reading Putnam", Blackwell, Cambridge (Massachusetts): Oxford 1995.

- ^ Colyvan, Mark, "Indispensability Arguments in the Philosophy of Mathematics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2004 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Putnam, H. Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Edited with Paul Benacerraf. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1964. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Putnam, H. (1981): "Brains in a vat" in Reason, Truth, and History, Cambridge University Press; reprinted in DeRose and Warfield, editors (1999): Skepticism: A Contemporary Reader, Oxford UP.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Putnam, H. Realism with a Human Face. Edited by J. F. Conant. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- ^ Putnam, H. 2012. From Quantum Mechanics to Ethics and Back Again. In his (Au.), De Caro, M. and Macarthur D. (Eds.) "Philosophy in an Age of Science". Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Putnam, H.. The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Putnam, Hilary (October 30, 2015). "What Wiki Doesn't Know About Me". Sardonic comment. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ Putnam, H. 2012. How to Be a Sophisticated "Naive Realist". In his (Au.), De Caro, M. and Macarthur D. (Eds.) "Philosophy in an Age of Science". Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Auxier, R. E., Anderson, D. R., & Hahn, L. E., eds., The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam (Chicago: Open Court, 2015), pp. 93–94.

- ^ Auxier, R. E., Anderson, D. R., & Hahn, L. E., eds., The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam (Chicago: Open Court, 2015), pp. 81–82.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Foley, M. (1983). Confronting the War Machine: Draft Resistance during the Vietnam War. North Carolina: North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2767-3.

- ^ Wolfe, Bertram David. "Strange Communists I Have Known", Stein and Day, 1965, p. 79.

- ^ Robert F. Barsky, Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent, Ch. 2: Undergraduate Years. "A Very Powerful Personality", MIT Press, 1997

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Hickey, L. P., Hilary Putnam (London / New York: Continuum, 2009).

- ^ Putnam, The Meaning of the Concept of Probability in Application to Finite Sequences (New York: Garland Publishing, 1990).

- ^ "Putnam, Hilary 1926- - Dictionary definition of Putnam, Hilary 1926- | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- ^ Deutsches Geschlechterbuch, vol. 214, Limburg 2002, p. 267-946

- ^ Hortsch, Michael. "Dr. Hans Nathan Kohn – ein Berliner Jüdischer Arzt und Forscher am Vorabend des Nationalsozialismus." Berlin Medical, Vol. 4:26–28 August 2007

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Linda Wertheimer (July 30, 2006). "Finding My Religion". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Ruth Anna Putnam, Wellesley College philosophy professor, dies at 91 - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- ^ http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/news/1.709318

- ^ http://www.firstthings.com/article/2008/10/004-wrestling-with-an-angel

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter P" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Epps, G., "Faculty Will Vote on New Procedures for Discipline", The Harvard Crimson, April 14, 1971.

- ^ Thomas, E. W., "Putnam Says Dunlop Threatens Radicals", The Harvard Crimson, May 28, 1971.

- ^ "NYT correction, March 6, 2005". The New York Times. March 6, 2005. Retrieved 2006-08-01.

- ^ The Spinoza Chair – Philosophy – University of Amsterdam

- ^ "Hilary Putnam: The Chosen People". Boston Review. Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- ^ "Hilary Putnam awarded The Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy". The Philosopher's Eye. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Hilary Putnam Wins the Rescher Prize for 2015!". University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Chakraborty, Sanjit. "Dr". PhilPapers.

- ^ "International Conference on THE PHILOSOPHY OF HILARY PUTNAM".

- ^ Weber, B., "Hilary Putnam, Giant of Modern Philosophy, Dies at 89", The New York Times, March 17, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bickle, John "Multiple Realizability", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2006 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Putnam, H. (1975) Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 88-459-0257-9

- ^ Fodor, J. (1974) "Special Sciences" in Synthese, 28, pp. 97–115

- ^ Fodor, J. (1980) "The Mind-Body Problem", Scientific American, 244, pp. 124–132

- ^ Block, Ned (August 1983). "What is Functionalism".

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (1988). Representation and Reality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Marhaba, Sadi. (2004) Funzionalismoin "Enciclopedia Garzantina della Filosofia" (ed.) Gianni Vattimo. Milan: Garzanti Editori. ISBN 88-11-50515-1

- ^ Levin, Janet, "Functionalism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2004 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Marvan, T., ed., What Determines Content? The Internalism/Externalism Dispute (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2006), pp. 70–75.

- ^ Davidson, D. (2001) Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 88-7078-832-6

- ^ Dell'Utri, Massimo. (2002) Olismo. Quodlibet. Macerata. ISBN 88-86570-85-6

- ^ C. S. Hill (ed.), "The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam", Fayetteville, Arkansas 1992.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Yablo, S. (November 8, 1998). "A Paradox of Existence".

- ^ Jump up to:a b Putnam, H. Mathematics, Matter and Method. Philosophical Papers, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975. 2nd. ed., 1985.

- ^ J J O'Connor and E F Robertson (April 1997). "Andrew Wiles summary".

- ^ S. Barry Cooper, Computability theory, p. 98

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (1963). "A note on constructible sets of integers". Notre Dame J. Formal Logic. 4 (4): 270–273. doi:10.1305/ndjfl/1093957652.

- ^ Boolos, George; Putnam, Hilary (1968). "Degrees of unsolvability of constructible sets of integers". Journal of Symbolic Logic. The Journal of Symbolic Logic, Vol. 33, No. 4. 33 (4): 497–513. doi:10.2307/2271357. JSTOR 2271357.

- ^ Boyd, Richard; Hensel, Gustav; Putnam, Hilary (1969). "A recursion-theoretic characterization of the ramified analytical hierarchy". Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. 141. 141: 37–62. doi:10.2307/1995087. JSTOR 1995087.

- ^ Putnam, H., Realism and Reason. Philosophical Papers, vol. 3.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wright, C. (1992), "On Putnam's Proof That We Are Not Brains-in-a-Vat", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 92.

- ^ Dell'Utri, M. (1990), "Choosing Conceptions of Realism: the Case of the Brains in a Vat", Mind 99.

- ^ Putnam, H. The Many Faces of Realism. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court, 1987.

- ^ Ernest Sosa, Putnam's Pragmatic Realism", The Journal of Philosophy, 90(12), Dec. 1993, pp. 605–626, esp. 605: "Putnam argues against 'metaphysical realism' and in favor of his own 'internal (or pragmatic) realism.'"

- ^ Jump up to:a b Curtis Brown (1988). "Internal Realism: Transcendental Idealism?". Midwest Studies in Philosophy (12): 145–55.

- ^ Devitt, M., Realism and Truth (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), p. 331.

- ^ Goodman, N., Fact, Fiction, and Forecast (Cambridge & London: Harvard University Press, 1979), p. 57.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Putnam, H. (1997). "A Half Century of Philosophy, Viewed from Within". Daedalus. 126 (1): 175–208. JSTOR 20027414.

- ^ Peter Clark and Bob Hale, eds., Reading Putnam. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

- ^ See also Philosophical Topics (vol. 20, Number 1, Spring 1992). And Hilary Putnam, "When 'Evidence Transcendence' is Not Malign", Journal of Philosophy, XCVIII, 11 (Nov. 2001), 594–600.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (November 9, 2015). "Wiki Catches Up a Bit". Sardonic comment. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ Feser, E., The Last Superstition: A Refutation of the New Atheism (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine Press, 2008), p. 234.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary. Sep. 1994. "The Dewey Lectures 1994: Sense, Nonsense, and the Senses: An Inquiry into the Powers of the Human Mind." The Journal of Philosophy 91(9):445–518.

- ^ Bartlett, T., "A Marriage of Minds: Hilary Putnam’s most surprising philosophical shift began at home", The Chronicle of Higher Education, September 10, 2017.

- ^ Reed, Edward (1997). "Defending Experience: A Philosophy For The Post-Modern World" in The Genetic Epistemologist: The Journal of the Jean Piaget Society, Volume 25, Number 3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bechtel, William and Mundale, Jennifer. Multiple Realizability Revisitedin Philosophy of Science 66: 175–207.

- ^ Kim, Sungsu. Testing Multiple Realizability: A Discussion of Bechtel and Mundale in Philosophy of Science. 69: 606–610.

- ^ Kim, Jaegwon. Multiple Realizability and the Metaphysics of Reduction on Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 52: 1–26.

- ^ Lewis, David (1969). "Review of Art, Mind, and Religion." Journal of Philosophy, 66: 23–35.

- ^ Richardson, Robert (1979). "Functionalism and Reductionism." Philosophy of Science, 46: 533–558.

- ^ Churchland, Patricia (1986). Neurophilosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ^ Searle, John. (1980). "Minds, Brains and Programs", Behavioral and Brain Sciences, vol.3. (online)

- ^ Block, Ned. (1980b). "Troubles With Functionalism", in Block (1980a).

- ^ Fodor, J. and Lepore, E. Holism: A Shopper's Guide. Blackwell. Oxford. 1992.

- ^ Dummett, Michael. The Logical Basis of Metaphysics. Harvard University Press. Cambridge (MA). 1978.

- ^ Penco, Carlo. Olismo e Molecularismo in Olismo ed. Massimo Dell'Utri. Quodlibet. Macerata. 2002.

- ^ Steinitz, Y. (1994), "Brains in a Vat: Different Perspectives", Philosophical Quarterly 44.

- ^ Brueckner, A. (1986), "Brains in a Vat", Journal of Philosophy 83.

- ^ Müller, V. C., "Bibliography of Hilary Putnam's Writings", PhilPapers, 1993.

References

- Bechtel, W. & Mundale, J. "Multiple Realizability Revisited" in Philosophy of Science 66: pp. 175–207.

- Bickle, J. "Multiple Realizability" in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(Fall 2006 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), (online).

- Brown, C. "Internal Realism: Transcendental Idealism?" Midwest Studies in Philosophy 12 (1988): pp. 145–155.

- Casati R. "Hilary Putnam" in Enciclopedia Garzanti della Filosofia. Gianni Vattimo (ed). Milan: Garzanti Editori, 2004. ISBN 88-11-50515-1.

- Churchland, P. Neurophilosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1986.

- Clark, P. & Hale, B. (eds.) Reading Putnam. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.

- Dummett, M. The Logical Basis of Metaphysics. Harvard University Press. Cambridge (MA) 1972.

- Fodor, J. & Lepore, E. Holism: A Shopper's Guide. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

- Foley, M. Confronting the War Machine. North Carolina: North Carolina Press. 1983. ISBN 0-8078-2767-3.

- Gaynesford, M. de Hilary Putnam, Acumen, 2006. (See Robert Maximilian de Gaynesford)

- Hickey, L. P., Hilary Putnam (London / New York: Continuum, 2009).

- Hill, C. S. (ed.) The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam, Fayetteville, Arkansas. 1992.

- Kim, J. "Multiple Realizability and the Metaphysics of Reduction." Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 52: 1–26.

- King, P. J. One Hundred Philosophers: The Life and Work of the World's Greatest Thinkers. Barron's 2004, p. 170.

- Lewis, D. "Review of Art, Mind, and Religion." Journal of Philosophy 66 (1969): 23–35.

- Matiyesavic, Y. 'Hilbert's Tenth Problem. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993. ISBN 0-262-13295-8.

- Penco, C. Olismo e Molecularismo in Olismo, ed. Massimo Dell'Utri. Quodlibet. Macerata. 2002.

- Putnam. Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Edited with P. Benacerraf. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, (1964). 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- ———. Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (1975).

- ———. "Brains in a Vat" in Reason, Truth, and History, Cambridge University Press (1981); reprinted in DeRose and Warfield, editors (1999): Skepticism: A Contemporary Reader, Oxford University Press.

- ———. Realism with a Human Face. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- ———. The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- ___. "Mind, Body and World in the Philosophy of Hilary Putnam". Interview wit Léo Peruzzo Júnior. In: Transformação Journal - UNESP, v.38, n.2, 2015.

- Richardson, R. "Functionalism and Reductionism." Philosophy of Science 46 (1979): 533–558.

- Searle, J. "Minds, Brains and Programs." Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3 (1980).

- Wertheimer, L. ""Finding My Religion." Boston Globe, July 30, 2006.

- Yablo, S. "A Paradox of Existence", June 8, 1998.

Further reading

- Y. Ben-Menahem (ed.), Hilary Putnam, Contemporary Philosophy in Focus, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005.

- P. Clark-B. Hale (eds.), Reading Putnam, Blackwell, Cambridge (Massachusetts)-Oxford 1995.

- C. S. Hill (ed.), The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam, Fayetteville, Arkansas 1992.

- M. Rüdel, Erkenntnistheorie und Pragmatik: Untersuchungen zu Richard Rorty und Hilary Putnam (dissertation), Hamburg 1987.

- Maximilian de Gaynesford, Hilary Putnam, McGill-Queens University Press / Acumen, 2006.

- Auxier, R. E., Anderson, D. R., & Hahn, L. E., eds., The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam, The Library of Living Philosophers, Open Court, Chicago, Illinois, 2015.

- Sanjit Chakraborty, Understanding Meaning and World: A Relook on Semantic Externalism, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, London, 2016.

External links

Quotations related to Hilary Putnam at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Hilary Putnam at Wikiquote- Hilary Putnam at PhilPapers

- Hilary Putnam at IMDb

- Hilary Putnam at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- An extensive bibliography

- An extensive directory

- Hilary Putnam at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- London Review of Books contributor page

- Hilary Putnam: On Mind, Meaning and Reality, Interview by Josh Harlan, The Harvard Review of Philosophy, spring 1992.

- "To Think with Integrity", Hilary Putnam's Farewell Lecture, The Harvard Review of Philosophy, Spring 2000.

- Putnam, "The Fact/Value Dichotomy and its critics"; Roundtable on Externalism audio/video lecture, audio discussion, March 2007, University College Dublin.

- Hilary Putnam – Externalism: Its Motivation And Its Critics, video of a lecture, delivered at Harvard University on October 4, 2007.

- A short film about the Putnam-Rorty debate and its influence on the pragmatist revival on YouTube

- The Moscow Center for Consciousness Studies video interview with Hilary Putnam 2010-04-21 (with transcript)

* * * * * * * * *

Hilary Putnam: Pragmatism and realism, Routledge

Conant, James and Zeglen, Urszula M. (eds.),

Hilary Putnam: Pragmatism and Realism, Routledge, 2002,

256pp, $80.00 (hbk), ISBN 0-415-25605-4.

Reviewed by Gabor Forrai, University of Miskolc

2002.07.11

The book is an outgrowth of a 1998 conference held at the Nicholas Copernicus University in Toru (Poland), for which Hilary Putnam was the keynote speaker. It contains eleven papers with responses by Putnam, and is divided into two parts, one on pragmatism and one on realism. Each part is prefaced by a short and well-focused introduction by Urszula M. Zeglen, which may be useful for those who did not keep up with the development of Putnam’s thought since the late seventies. Some papers are directly addressed to Putnam, seeking to challenge or support him on particular points, but more of them aim at developing themes on which Putnam has a view. I will discuss only some of the papers; the others will be listed at the end of this review.

Ruth Anna Putnam’s “Taking pragmatism seriously” and Hilary Putnam’s own “Pragmatism and nonscientific knowledge” survey the issues with respect to which the latter claims to be an heir to classical pragmatism. The most important of these are as follows:

(1) Philosophy should not lose contact with general human concerns. What this means is that the common man’s views which are integral to human practices should not be brushed aside as if they were necessarily inferior to the sophisticated technical doctrines of professional philosophers. Even though the commonly held views may not be right as they stand, the philosophical views which are opposed to them – such as skepticism about the external world, indirect realist theories of perception, denial of the cognitive status of ethics – are more suspect. It follows then that one important task for a philosopher who takes pragmatism seriously is to expose the fallacies underlying those philosophical doctrines, which seem incredible for the layman. No wonder that Wittgenstein and Austin are just as much philosophical heroes for Putnam as Peirce, James and Dewey.