Towards an Ecological Neuroscience:

Aspects of the Nature of Things

According to Process Philosophy

by S. David Stoney

Ph.D.Dept of Physiology

December 17, 2001

"There are deep similarities between Whitehead's idea of the process by which nature unfolds and the ideas of quantum theory. Whitehead says that the world is made of actual 'occasions', each of which arises from potentialities created by prior actual occasions. These actual occasions are 'happenings' modeled on experiential events, each of which comes into being and then perishes, only to be replaced by a successor. It is these experience-like 'happenings' that are the basic realities of nature, according to Whitehead, not the persisting physical particles that Newtonian physics took [to] be the basic entities.

Similarly, Heisenberg says that what is really happening in a quantum process is the emergence of an 'actual' from potentialities created by prior actualities. In the orthodox Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory the actual things to which the theory refer[s] are increments in 'our knowledge'. These increments are experiential events. The particles of classical physics lose their fundamental status: they dissolve into diffuse clouds of possibilities. At each stage of the unfolding of nature the complete cloud of possibilities acts like the potentiality for the occurrence of a next increment in knowledge..." Henry P. Stapp, author of Mind, Matter, and Quantum Mechanics, in an invited paper at the Silver Anniversary International Whitehead Conference, Claremont, CA, August 4-9, 1998. See http://www-physics.lbl.gov/~stapp/wh2.txt

I. Introduction.

The problem, of course, with the materialistic approach is that it doesn't validate that which is the only thing we are really sure of, our own experience. This is dangerous for ourselves as persons of value and for science. Whitehead's bold step was to presume the reality of experience and process all the way up, from the most "elementary" of particles to the mind of God, so to speak. The biologist, Conrad H. Waddington, described Whitehead's idea as follows:

"Whitehead was bold enough to take on, face to face, the most difficult of intellectual problems - the fact that each one of us has a conscious experience, whereas in science we try to account for the behavior or things by means of concepts or entities - atoms, waves, fundamental particles, and so on - whose definition does not contain any reference to consciousness. Whitehead argued that this is not good enough: you have either got to have consciousness, or at least something of that general kind, everywhere, or nowhere; and since it is obviously in us, and cannot be nowhere, it must therefore be everywhere, presumably mostly in very rudimentary form." Conrad A. Waddington, cited in John A. Jungerman, World in Process: Creativity and Interconnection in the New Physics, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pgs. 86 & 87, 2000.

David Ray Griffin had this to say about the universality of experience:

"Panexperientialism [another name for process philosophy] is based upon the... assumption that we can, and should, think about the units comprising the physical world by analogy with our own experience, which we know from within. The supposition, in other words, is that the apparent difference in kind between our experience, or our "mind," and [other] entities... is an illusion, resulting from the fact that we know them in two different ways: we know our minds from within, by identity, whereas in sensory perception... we know [other entities] from without. Once we realize this, there is no reason to assume them really to be different in kind." David Ray Griffin, Religion and Scientific Naturalism: Overcoming the Conflicts, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pg. 2000.

So, process thought views experiential events, understood as actual occasions, not substances, as fundamental. Although brief, actual occasions bring forth, over and over again, the objective world and our awareness of it. The following description, which relies heavily on the mercifully short introductory chapter in Jungerman's (see above) book, will present, in a somewhat didactic form, a brief description of the basic features of the process approach. This chapter from Jungerman's book is on reserve at the MCG library. The other books and copies on reserve at the MCG Library have more thorough descriptions.

II. Some important process ideas.

(See Figure below from Jungerman, pg. 11, see )

- Actual occasions, understood as experiential events, are primary, not substances ("mere matter").

- Each event feels the feelings of - is connected to (i.e., prehends) - earlier events as well as the dominant occasion of experience of the universe. Actual occasions are "drops of experience."

- Although strongly influenced by the past, events have aims (goals), namely to maximize creativity and intensity of feeling, that arise due to their participation with more dominant occasions of experience.

- Thus, events have some capacity, however slight, to select among alternatives. This allows for novelty.

- Immediately upon grasping or incorporating the feelings of past events and potential goals, the actual occasion "perishes" into objectivity, becoming data (potentiality) for the next actual occasion, which immediately succeeds it.

- This process makes concrete a novel, present unity with duration, in which the prehensions and the subjective goals are integrated. Whitehead calls this process of self-determination a "concrescence."

- An event that has completed it's concrescence has achieved satisfaction and becomes "objectively immortal" as a datum to be prehended by future experiential events.

- Thus existence is a series of coming into beings (concrescences), each occasion of which brings the world with it as data (See and reference 8, especially Kevin O'Regan's notion of "the world as an outside memory," in the Introduction).

- Subjects and objects are different in time, not in kind.

- Compound individuals (societies of prehensions with dominant occasions of experience; such as living creatures) must be distinguished from mere aggregates (societies of actual occasions without dominant members; such as rocks).

- Any creature is a highy integrated, dynamic pattern of interdependent events. Its parts contribute to, and are modified by, the unified activity of the whole, i.e., by the dominant occasion of experience.

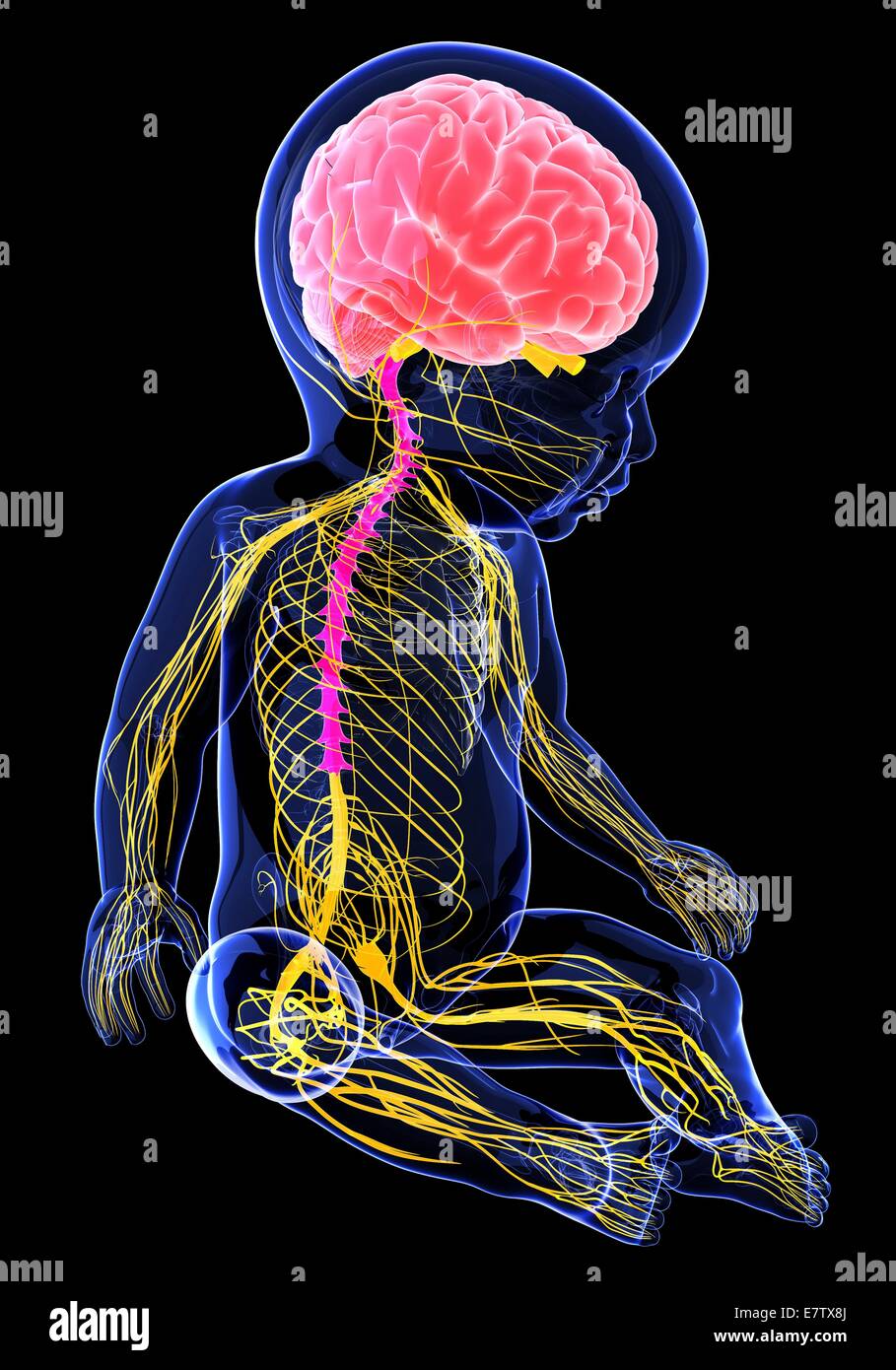

- The dominant occasion of experience integrates the lower level actual occasions into a unity of purpose. For human beings, the dominant occasion of experience constitutes the mind (or psyche, or soul) and the integration of the experience of all subordinate actual occasions provides for conscious awareness from an embodied perspective.

- Existence is becoming: The many become one and are increased by one

- Most experience is nonconscious (nonsensory) experience. All actual occasions share in having nonconscious experience; conscious experience arises in only a few compound individuals.

- The universe appears interconnected by a web of prehensions and probably has its own dominant occasion of experience.

- For any actual occasion, the future is open, i.e., unpredictable because of the alternatives (potentialities) available to it. This is the basis for the appearance of novelty.

- Conscious awareness is not an unbroken stream of experience, but rather is a series of experiential events, each of which has spatial as well as temporal extension.

- Memory and perception are alike in that they each are an intuition of previous actualities

Jungerman describes this figure as follows:

"The event begins with a prehension, a grasping of previous events, including the prior events of the enduring society to which it belongs, by the physical pole. The physical pole is the part of the event that interacts with the external world. This information passes into the mental pole. The mental pole is internal to the the event. It synthesizes the data coming to the physical pole with the goals of this becoming event. This process is termed a concrescence. When the synthesis is accomplished, all the data are simplified in a satisfaction... The mental pole's creative simplification by selection among alternatives may lead to increased intensity of experience and to novelty. It may lead to a new whole (synthesis) through emergence with other events. On the other hand, a single electron's experience may be viewed as being so dominated by its physical pole that upon concrescence its characteristics are repeated over and over. It becomes an enduring individual that retains the same character over a long period of time. After its satisfaction, an event is said to be objectively immortal, as it becomes a datum to be prehended by future events. Note that the event takes place in a finite time, which flows from the past to the future..." (pg. 11 & 12)

Nicholas Rescher, in Process Metaphysics (see), notes that this approach is a point of view that accepts that processes and activities are more important than things and substances. He listed the following differences:

III. Prehensions

The importance of this concept cannot be overstated. Each actual occasion prehends - i.e., grasps or incorporates - data from the past, as well as subjective aim from dominant occasions of experience. Thus, an actual occasion is an action.

In addition to such positive prehensions, negative prehensions, which can exclude the sharing of feelings can also occur. Jungerman describes prehension as follows:

In addition to such positive prehensions, negative prehensions, which can exclude the sharing of feelings can also occur. Jungerman describes prehension as follows:

"Prehension describes the connection between past and present events, no matter how elementary. The present event, which is partially self-determining, makes a creative selection among data from all past events and from alternative future possibilities, goals, or aims. Such aims are only potentialities until the selection actualizes them... At some level we are aware of the mysterious 'otherness' of our fellows creatures and take them into ourselves, informing our own actuality - not just in appreciation, but rather in recognizing that the 'other' is [sic] in some sense constitutes ourselves. We are all inextricably linked in the matrix of creation " (pg. 7 & 8)

At a more concrete level of description, consider Charles Hartshorne's words (which describe, I believe, the doorway to understanding of placebo effects):

"Cells can influence our human experiences because they have feelings that we can feel. To deal with the influences of human experiences on cells, one turns this around. We have feelings that cells can feel." (pg. 12)

IV. Dominant occasions of experience

No doubt there is a dominant occasion of experience for the event known as a hydrogen atom, just as there are dominant occasions of experience for the events known as you and I. The prehension of the proton by its electron (and vice versa) no doubt gave rise to an experience that is, from our perspective, indescribable, except to say that there presumably is more enjoyment associated with that concrescence than, for example, with the concrescence of the quarks and gluons that make up the proton. The idea that societies of actual occasions, especially those associated with compound individuals, are capable of more enjoyment and more complex experiences than simple assemblies of events is fundamental to process thought. Failure to take note of this feature is one of the most common, erroneous reasons for dismissing panexperientialism: "Oh, those folks are crazy, they believe that electrons (or rocks) are conscious."

Process thought explicitly recognizes that creation of order, increasing complexity, and emergence of novelty are historical facts. Such an outcome is, according to process thought, the natural outcome of a society of occasions of experience maximizing its satisfaction or enjoyment. Jungerman quotes Waddington in this regard:

"Whitehead insisted that an event is not merely an assemblage of numerous relations between many different things thrown together in a disorderly heap. On the contrary the various 'feelings' of one for another are organized into something with a specific and individual character... Organization occurs when the relations are of such a kind that they tend to stabilize the general pattern against influences which might disturb it. That is to say, organization confers on the entity an enduring individuality which a mere assemblage lacks." (pg. 118)

In this regard, I believe that it is noteworthy that Whitehead's metaphysics leads naturally to an introduction of the divine. I simplistically [can now] view the divine "as a field of pure positive affect that pervades the entire universe and which participates with the dominant occasion of experience of that universe." The accord between modern science and process theology means that the estrangement between religion and science may dissipate in a reconstructive postmodern era. Given the threat to societal stability posed by abrupt global climate change, it is comforting that we may be able to use all the tools at our disposal to meet that enormous challenge to human progress.

V. Why bother?

Isn't the present primarily physicalist approach close enough for government work? Well, yes, provided that the goal is to maintain the status quo and continue the current modern trajectory toward a deconstructive postmodern ("posthuman") future where we can all take great delight in being naught but souless "bags of genes and chemicals" bumping about in a blighted environment. If perchance that does not seem desirable, then perhaps it is time to admit that 100% allegiance to the present approach may be suicidal. Isn't neuralism, especially in conjunction with a "revolt of the elite" - for whom the accumulation of more and more 'stuff,' without relation to actual need, has become the highest good - quite nihilistic toward human value, not to mention survival of the world as a viable ecosystem?

I suggest taking a bold step. Integrate information about abrupt global climate change into our base of conscious knowledge so that it can act as a "cognitive capstone," deflecting the trajectory of embodied human consciousness away from its highly alienated, 'posthuman' target and towards a more humane, postcritical mindscape. According to this scheme, the competitive, tribal mentalities that have dominated the first part of this interglacial phase must give ground to more cooperative, postcritical, participatory mentalities not dominated by unconscious fear. A postcritical worldview will consciously recognize abrupt global climate change and the critical need to break free of the conditioned thinking of the past where 'our knowledge' of abrupt global climate change has been almost entirely in the form of unconscious fear. The figure below illustrates some alternative trajectories for embodied human consciousness.

As alluded to above, the data about cyclic climate change - at least for the last three million years or so of earth's geologic history - where long, cold, arid glacial phases have been interrupted by short, warm, wet interglacial phases, is startling and very worrisome. The last three million years was, by the way, the period when the hominid line diverged from its primate forebears, leading, according to the fossil record, to the appearance of modern Homo sapiens with brains such as ours in size, around 50,000 to 100,000 years ago. This data is, at least in broad outline, firm and widely accepted.

"Cyclic climate pattern of alternating cold, dry glacial periods and warm, wet interglacial periods. This pattern has prevailed during the current ice age, which has lasted for three million years. Transitions between glacial and interglacial phases may occur within as short a period of time as a decade. Marked variations in sea level occurred near the end of the last two interglacial periods. Upward slope of interglacial phase temperatures reflect the progressive decrease in earth's albedo as the polar ice caps shrink. Insert shows rapid fluctuations in temperature that occurred during the last glacial phase."

So, our best guesses are that the three million year old climate cycle continues and the currently warming interglacial phase will come to an end, perhaps abruptly, perhaps soon. What we don't know is exactly when and how the next glacial phase will begin. However, to wait until we do know "for sure" will almost certainly be too late. Even though we have developed practically all the tools (except perhaps the political will and spiritual fortitude) we need to deal with this problem during the first part of this interglacial phase, we should not underestimate the resistance that will arise to changing the ways we do business.

If we have 100 years to get used to the fact that those of us who live in northern latitudes are merely 'renters,' well, then we could probably do a little. If we have 500 years we could do a great deal. To put it into stark terms, consider that contemporary thought forms appear to be able to do relatively little towards stemming population growth. This makes it probable that interglacial phase population growth will approximate the curve shown in part A of the figure below: population increases as long as food supply allows.

If we have 100 years to get used to the fact that those of us who live in northern latitudes are merely 'renters,' well, then we could probably do a little. If we have 500 years we could do a great deal. To put it into stark terms, consider that contemporary thought forms appear to be able to do relatively little towards stemming population growth. This makes it probable that interglacial phase population growth will approximate the curve shown in part A of the figure below: population increases as long as food supply allows.

The problem for the postcritical mind: Learning to learn to live in an ecologically sustainable way during interglacial phases.

Now, in the event of a rapid cooling (or worse, a "1-2 punch" of rapid warming and sea level rise followed by rapid cooling) the population downsizing will almost certainly be extremely catastrophic. Is that how this phase of civilization is going to end? Let's at least try opening ourselves to a new infusion of creativity and novelty for the last part of this interglacial period.

Surely we should work towards having a population that will be closer to a level sustainable through the transition to the next glacial phase. Surely we should work for the maintenance of civilization, freedom, and the individualized modes of consciousness that civilization supports. Who knows what can be accomplished in our society if we Homo sapiens sapiens are willing to work together, if we are willing to strive to be an example for the rest of the world.

If not, if we bow our heads and slink into the posthuman future of denial, alienation, and despair, then the question must arise as to whether or not human beings are truly conscious. What use is freedom without consciousness?

Surely we should work towards having a population that will be closer to a level sustainable through the transition to the next glacial phase. Surely we should work for the maintenance of civilization, freedom, and the individualized modes of consciousness that civilization supports. Who knows what can be accomplished in our society if we Homo sapiens sapiens are willing to work together, if we are willing to strive to be an example for the rest of the world.

If not, if we bow our heads and slink into the posthuman future of denial, alienation, and despair, then the question must arise as to whether or not human beings are truly conscious. What use is freedom without consciousness?

VI. References and Notes

1. The disutility of conceiving of human beings in strictly physicalist terms was addressed with vigor by philosopher/scientist Michael Polanyi:

"The ideal of strictly objective knowledge, paradigmatically formulated by Laplace, continues to sustain a universal tendency to enhance the observational accuracy and systematic precision of science, at the expense of its bearing on its subject matter...[Science may be characterized as harboring] a misguided intellectual passion - a passion for achieving absolutely impersonal knowledge which, being unable to recognize any persons, presents us with a picture of the universe in which we ourselves are absent. In such a universe there is no one capable of creating and upholding scientific values; hence there is no science."

The story of the Laplacean fallacy suggests a criterion of consistency. It shows that our conceptions of man and human society must be such as to account for man's faculty in forming these conceptions and to authorize the cultivation of this faculty within society. Only by accrediting the exercise of our intellectual passions in the act of observing man, can we form conceptions of man and society which both endorse this accrediting and uphold the freedom of culture in society. Such self-accrediting, or self-confirmatory, progression will prove an effective guide to all knowledge of living beings." (Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy, 1958. Emphasis added)

2. John A. Jungerman, World in Process: Creativity and Interconnection in the New Physics, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pgs. 86 & 87, 2000.

3. Henri Bergson, in Introduction to Metaphysics (NY: G. P. Putnam's Sons, pg. 12, 1912), expressed it this way:

"...to live is to grow old. But it may just as well be compared to a continual rolling up, like that of a thread on a ball, for our past follows us, it swells incessantly with the present that it picks up on its way; and consciousness means memory."

4. Nicholas Rescher, Process Metaphysics: An Introduction to Process Philosophy, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pg. 35, 1996.