There is no abstract art. You must always start with something.

Afterwards you can remove all traces of reality.

There's no danger then, anyway, because the idea of

the object will have left an indelible mark.

- Pablo Picasso

May Facebook friend Greg Laughery recently asked the question of self without self. I would like to intermix his thoughts with some of my own. Here they are... together.... - res

The question of whether we can be other than we are is significant. Put another way, "Is it possible to be other than who we are?" Both questions relate directly to our essential essence, our core self, our inner being. This is a different question than addressing whether we may act ethically or morally regardless of our inner self. It is the Christian position that we can and must act ethically and morally as much as we can in ourselves given any state of affairs we are behaving within at that time. It is why a penitent faith is so crucially important... without it we live unredeemed and unfulfilled spiritually. Statedly, "God has come into this world (and will remain in this world until creation's end) to redeem it" from its "lack" that it might be more fully "alive" to His Spirit of love and grace. Some call this lack imperfection, sin, a disobedience, and so forth. It is that indescribable something that prevents our spirit from soaring, reclaiming, healing, rectifying, binding, hearing, listening, doing, and unifying all around itself with new sight, perspective, union, solidarity of very creation itself.

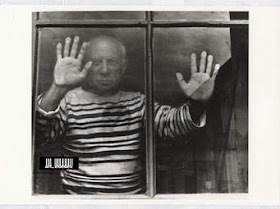

Thus, the significance of Picasso attempting to paint a painting without any trace of Picasso in it should give rise to thought. Could he do it? Was it possible for him to be so disengaged from his work that its meaning and interpretation would be entirely up to the viewer? Picasso, intriguingly, may have set out to accomplish this, but ultimately could not.

|

| Guernica - Link to Portrait |

What Picasso was attempting – a total distinction of the subject from the object – is a deceptive goal. Neutrality is not a plausible option for any person since "intentionality is an unrelenting dimension of who we are." After all, being erased, unnoticed, excluded from participation in creativity - or life itself - would not be human. We are present, involved, and continually leaving traces of ourselves in time and space.

This dynamic truth then amounts to the gift of a perspective of the world and humanity that shows to us that "the subject and the object" are commissioned to "interact" with each other. Meaning and interpretation, therefore, can never be reduced to the viewer. Why? Because the "creator-painter" always plays a role in what’s created-painted. It is essentially who we are. And it is this role of discovery that gives to ourselves the meaning, drive, purpose, and reason for living each day as if we are re-discovering who we are in relation to all other living created things. The relational world we live in is the telling world of being. Our identity ceases within and outside itself if it were not relational. Yet we are, and are to exuberantly claim this life force we possess that it might be fully reclaimed by the Spirit of God to the glory of God and to the furtherance of His evolving, redeeming, renewing creation.

R.E. Slater

January 22, 2019

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Pablo Picasso Biography

As a significant influence on 20th-century art, Pablo Picasso was an innovative artist who experimented and innovated during his 92-plus years on earth. He was not only a master painter but also a sculptor, printmaker, ceramics artist, etching artist and writer. His work matured from the naturalism of his childhood through Cubism, Surrealism and beyond, shaping the direction of modern and contemporary art through the decades. Picasso lived through two World Wars, sired four children, appeared in films and wrote poetry. He died in 1973.

Early Years: 1881-1900

Although he lived the majority of his adult years in France, Picasso was a Spaniard by birth. Hailing from the town of Málaga in Andalusia, Spain, he was the first-born of Don José Ruiz y Blasco and María Picasso y López. He was raised as a Catholic, but in his later life would declare himself an atheist.

Pablo Picasso's father was an artist in his own right, earning a living painting birds and other game animals. He also taught art classes and curated the local museum. Don José Ruiz y Blasco began schooling his son in drawing and oil painting when the boy was seven, and he found the young Pablo to be an apt pupil.

Picasso attended the School of Fine Arts in Barcelona, where his father taught, at 13 years of age. In 1897, Picasso began his studies at Madrid's Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, which was Spain's top art academy at the time. Picasso attended only briefly, preferring to roam the art exhibits at the Prado, studying works by El Greco, Francisco Goya, Diego Veláquez and Zurbáran.

During this nascent period of Picasso's life, he painted portraits, such as his sister Lola's First Communion. As the 19th century drew to a close, elements of Symbolism and his own interpretation of Modernism began to be apparent in his stylized landscapes.

Middle Years: 1900-1940

In 1900, Picasso first went to Paris, the center of the European art scene. He shared lodgings with Max Jacob, a poet and journalist who took the artist under his wing. The two lived in abject poverty, sometimes reduced to burning the artist's paintings to stay warm.

Before long, Picasso relocated to Madrid and lived there for the first part of 1901. He partnered with his friend Francisco Asis Soler on a literary magazine called "Young Art," illustrating articles and creating cartoons sympathetic to the poor. By the time the first issue came out, the developing artist had begun to sign his artworks "Picasso," rather than his customary "Pablo Ruiz y Picasso."

Blue Period

The Picasso art period known as the Blue Period extended from 1901 to 1904. During this time, the artist painted primarily in shades of blue, with occasional touches of accent color. For example, the famous 1903 artwork, The Old Guitarist, features a guitar in warmer brown tones amid the blue hues. Picasso's Blue Period works are often perceived as somber due to their subdued tones.

Historians attribute Picasso's Blue Period largely to the artist's apparent depression following a friend's suicide. Some of the recurring subjects in the Blue Period are blindness, poverty and the female nude.

Rose Period

The Rose Period lasted from 1904 through 1906. Shades of pink and rose imbued Picasso's art with a warmer, less melancholy air than his Blue Period paintings. Harlequins, clowns and circus folk are among the recurring subjects in these artworks. He painted one of his best-selling works during the Rose Period, Boy with a Pipe. Elements of primitivism in the Rose Period paintings reflect experimentation with the Picasso art style.

African Influence

During his African art and Primitivism period from 1907 to 1909, Picasso created one of his best-known and most controversial artworks, Les Damoiselles d'Avignon. Inspired by the angular African art he viewed in an exhibit at the Palais de Trocadero and by an African mask owned by Henri Matisse, Picasso's art reflected these influences during this period. Ironically, Matisse was among the most vocal denouncers of "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" when Picasso first showed it to his inner circle.

Analytic Cubism

From 1907 to 1912, the artist worked with fellow painter Georges Braque in creating the beginnings of the Cubist movement in art. Their paintings utilize a palette of earth tones. The works depict deconstructed objects with complex geometric forms.

His romantic partner of seven years, Fernande Olivier, figured in many of the artist's Cubist works, including Head of a Woman, Fernande (1909). Historians believe she also appeared in "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon." Their relationship was tempestuous, and they separated for good in 1912.

Synthetic Cubism

This era of Picasso's life extended from 1912 to 1919. Picasso's works continued in the Cubist vein, but the artist introduced a new art form, collage, into some of his creations. He also incorporated the human form into many Cubist paintings, such as Girl with a Mandolin (1910) and Ma Jolie (1911-12). Although a number of artists he knew left Paris to fight in World War I, Picasso spent the war years in his studio.

He had already fallen in love with another woman by the time his relationship with Fernande Olivier ended. He and Eva Gouel, the subject of his 1911 painting, "Woman with a Guitar," were together until her untimely death from tuberculosis in 1915. Picasso then moved into a brief relationship with Gaby Depeyre Lespinesse that lasted only a year. In 1916-17, he briefly dated a 20-year-old actress, Paquerette, and Irene Lagut.

Soon thereafter, he met his first wife, Olga Khoklova, a ballet dancer from Russia, whom he married in 1918. They had a son together three years later. Although the artist and the ballerina became estranged soon thereafter, Picasso refused to grant Khoklova a divorce, since that meant he would have to give her half of his wealth. They remained married in name only until she died in 1955.

Neoclassicism and Surrealism

The Picasso art period extending from 1919 to 1929 featured a significant shift in style. In the wake of his first visit to Italy and the conclusion of World War I, the artist's paintings, such as the watercolor Peasants Sleeping (1919) reflected a restoration of order in art, and his neoclassical artworks offer a stark contrast to his Cubist paintings. However, as the French Surrealist Movement gained traction in the mid-1920s, Picasso began to reprise his penchant for Primitivism in such Surrealist-influenced paintings as Three Dancers (1925).

In 1927, the 46-year-old artist met Marie-Therese Walter, a 17-year-old girl from Spain. The two formed a relationship and Marie-Therese gave birth to Picasso's daughter Maya. They remained a couple until 1936, and she inspired the artist's "Vollard Suite," which consists of 100 neoclassical etchings completed in 1937. Picasso took up with artist and photographer Dora Maar in the late '30s.

During the 1930s, Picasso's works such as his well-known Guernica, a unique depiction of the Spanish Civil War, reflected the violence of war time. The menacing minotaur became a central symbol of his art, replacing the harlequin of his earlier years.

Later Years: 1940-1973

During World War II, Picasso remained in Paris under German occupation, enduring Gestapo harassment while he continued to create art. Some of the time, he wrote poetry, completing more than 300 works between 1939 and 1959. He also completed two plays, "Desire Caught by the Tail," and "The Four Little Girls."

After Paris was liberated in 1944, Picasso began a new relationship with the much younger art student Francoise Gilot. Together, they produced a son, Claude, in 1947, and a daughter, Paloma, in 1949. Their relationship was doomed like so many of Picasso's previous ones, however, due to his continual infidelities and abuse.

He focused on sculpture during this era, participating in an international exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1949. He subsequently created a commissioned sculpture known as the Chicago Picasso, which he donated to the U. S. city.

In 1961, at the age of 79, the artist married his second and last wife, 27-year-old Jacqueline Roque. She proved to be one of his career's greatest inspirations. Picasso produced more than 70 portraits of her during the final 17 years he was alive.

As his life neared its end, the artist experienced a flurry of creativity. The resulting artworks were a mixture of his previous styles and included colorful paintings and copper etchings. Art experts later recognized the beginnings of Neo-Expressionism in Picasso's final works.

Picasso's Influence on Art

As one of the greatest influences on the course of 20th-century art, Pablo Picasso often mixed various styles to create wholly new interpretations of what he saw. He was a driving force in the development of Cubism, and he elevated collage to the level of fine art.

With the courage and self-confidence unhindered by convention or fear of ostracism, Picasso followed his vision as it led him to fresh innovations in his craft. Similarly, his continual quest for passion in his many romantic liaisons throughout his life inspired him to create innumerable paintings, sculptures and etchings. Picasso is not just a man and his work. Picasso is always a legend, indeed almost a myth. In the public view he has long since been the personification of genius in modern art. Picasso is an idol, one of those rare creatures who act as crucibles in which the diverse and often chaotic phenomena of culture are focussed, who seem to body forth the artistic life of their age in one person.