How to Read the Old Testament in Light of the New Testament

Daniel Kirk recently reviewed his colleague Dr. Goldingay's new book, "Do We Really Need the New Testament?" which asks the question how to read the Old Testament as a New Testament Christian.

Basically it advocates that the Christian learn to read the OT on its own without reading church history's re-interpretation of it through Jesus. Which is a fair point to be made - but impossible to do in light of Jesus.

At some point the text of the Old Testament should be discerned and interpreted in a twofold manner:

If we are to read the OT alone without any interpretation to it by the NT then we must do so without the interpretation of the church councils which present doctrines like the "Trinity" into the mainstream of OT Jewish theology. Such doctrines were foreign to the theology of the ancient Jews even though within the texts of Scripture itself it can be seen by the "backwards glance" through the lens of the New Testament that the church doctrine of the Trinity is not as foreign a concept as first thought. But again, that is with the benefit of historical hindsight.

This may also be inferred by other "Christian doctrinal formulations" which developed after Jesus and not before during the period of the Old Testament. As such, Christian doctrine is absent Old Testament Jewish theology as it developed its own theologies about God and their place within God's purposes for a time and people removed from the Christ-event to come.

So then, to read the Old Testament on its own and within its own historical periodicity is to attempt to understand its Scriptures without the theological perspective of the New Testament church and its councils which were not historically present in the OT.

Basically it advocates that the Christian learn to read the OT on its own without reading church history's re-interpretation of it through Jesus. Which is a fair point to be made - but impossible to do in light of Jesus.

At some point the text of the Old Testament should be discerned and interpreted in a twofold manner:

- On its own apart from the New Testament's testimony to Jesus, and

- Coupled with the New Testament's testimony of Jesus even as its gospel writers had clearly done.

If we are to read the OT alone without any interpretation to it by the NT then we must do so without the interpretation of the church councils which present doctrines like the "Trinity" into the mainstream of OT Jewish theology. Such doctrines were foreign to the theology of the ancient Jews even though within the texts of Scripture itself it can be seen by the "backwards glance" through the lens of the New Testament that the church doctrine of the Trinity is not as foreign a concept as first thought. But again, that is with the benefit of historical hindsight.

This may also be inferred by other "Christian doctrinal formulations" which developed after Jesus and not before during the period of the Old Testament. As such, Christian doctrine is absent Old Testament Jewish theology as it developed its own theologies about God and their place within God's purposes for a time and people removed from the Christ-event to come.

So then, to read the Old Testament on its own and within its own historical periodicity is to attempt to understand its Scriptures without the theological perspective of the New Testament church and its councils which were not historically present in the OT.

Which gets to the idea then of "How does one read the OT in its own setting?" Or more to the point, "How does one read the OT without reading it through the grid of NT theology?"

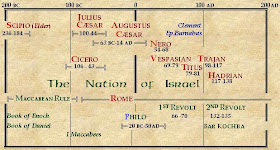

The best help and guide here would be from the ancient Jewish theologies themselves as they were formulated through the Inter-Testamental period between the Old and New Testament eras.

History of Jewish Theology

I find the Inter-Testament period between the Old and New Testaments to be significant for any number of reasons:

The best help and guide here would be from the ancient Jewish theologies themselves as they were formulated through the Inter-Testamental period between the Old and New Testament eras.

History of Jewish Theology

I find the Inter-Testament period between the Old and New Testaments to be significant for any number of reasons:

- It becomes the period of time when Israel comes to finally understand the full ramifications of God's covenants to Abraham, Moses, and David (the Abrahamic, the Mosaic, and the David covenants);

- When Israel comes to understand the full meaning of the blessings and curses that attenuated those ancient covenants when obeyed or broken;

- When Israel finally comes to understand the meaningfulness of God's promises to their daily lives as a true blessing - and not merely as a bothersome regulation or rule of authority;

- When Israel finally discovers what covenantal restoration really means in light of its repentance and confession from sins and transgressions to be fully restored to rightful fellowship to her Creator-God on the basis of blood sacrifice; or even,

- The scope of God's love and faithfulness to His chosen people at the height of their disobedience to Him (at the last, the Abrahamic covenant was ever-and-always enacted upon the faithfulness of God and NOT the faithfulness of Abraham nor his descendants).

Moreover, post-exilic Israel (now Judah) had the benefit of hindsight over its many years of redemption from Egypt as they tried to live as a people who worshipped a unique God quite unlike the gods of their polytheistic neighbors around them. A God whose expectations of ethics and morality were wholly unlike the ethics and moralities of the other gods of the nations. A God whose covenantal faithfulness and love was not really understood until experienced through difficult times of failure and breakage among his people as they strove to understand this God they worshipped and clung too (sic, the Psalms are full of the pathos of covenantal struggle and restoration).

The Inter-Testamental Period Demanded Owning up to Failure

After the times of the priests and early judges; after the times of the kings and their fickled people; after the times of the early and later prophets; now we come to Ezra and Nehemiah as they rebuild a people who have suffered long and hard for their sin and faithlessness. For sins that the God had warned them would create separation and struggle not only from Himself but from one another:

And so, after all this history, all the many stories of brokenness and restoration, Israel now stands on the other side of history and takes the long look back at itself. Its rich culture lost on the swords of so many destitutions. Its bright promise blighted in the night of its many sins. Its deep longings to be faithful to their loving God, their godly heritage, and to one another lost in the ragged return of its survivors coming to terms with the despair of their final and horrific holocaust.

After the times of the priests and early judges; after the times of the kings and their fickled people; after the times of the early and later prophets; now we come to Ezra and Nehemiah as they rebuild a people who have suffered long and hard for their sin and faithlessness. For sins that the God had warned them would create separation and struggle not only from Himself but from one another:

- From Himself as their Sovereign who granted the freedom of the heart to follow other loves, gods, and fallacious thinking; and

- From one another as evil entered into their assemblies causing this Godly separation to become harder, deeper, more grievous, with every twist-and-turn of the fallacious heart.

And so, after all this history, all the many stories of brokenness and restoration, Israel now stands on the other side of history and takes the long look back at itself. Its rich culture lost on the swords of so many destitutions. Its bright promise blighted in the night of its many sins. Its deep longings to be faithful to their loving God, their godly heritage, and to one another lost in the ragged return of its survivors coming to terms with the despair of their final and horrific holocaust.

Here now is Israel struggling to be a country lost amid the ruins of its own civilization as the world stage shifted from one empire to the next. From a Greek empire transitioning to a Macedonian empire ruled by a king named Alexander the Great. That fearless ruler who would conquer Asia Minor where Babylon once ruled; the land of Egypt where the Pharaohs once ruled; the lands of once mighty Persia; and finally find his eclipse in the terrible lands of India to vast its scourages, plagues, and tribes.

Upon Alexander's demise came the trading sea kingdoms of the Middle East and North African regions struggling against Egypt to the east and west and against Rome, to the north, becoming mightier and fiercer with every victory against nearer and further Gaul (Spain, France, Germany) as it came to its zenity to then turn its gaze southwards and across the blue Mediterranean.

Little Israel lay now in the ruins of world dominions seeking as it could the answers to a shattered faith that could give few answers but asked many unanswerable questions. Consisting of a covenanted people who remembered the religion of their fathers and sought to give this rich heritage a voice through their scrolls and scribes. Through new rules and laws (Mishna et al). Through a priesthood rededicating itself to its God who seemed no longer close. Or to care. Who was thought to be as faraway as His forsaken children were from themselves struggling to survive in a harsh world made harsher in the lostness of their faith.

Little Israel lay now in the ruins of world dominions seeking as it could the answers to a shattered faith that could give few answers but asked many unanswerable questions. Consisting of a covenanted people who remembered the religion of their fathers and sought to give this rich heritage a voice through their scrolls and scribes. Through new rules and laws (Mishna et al). Through a priesthood rededicating itself to its God who seemed no longer close. Or to care. Who was thought to be as faraway as His forsaken children were from themselves struggling to survive in a harsh world made harsher in the lostness of their faith.

A History Created and Remembered in the Aftermaths of Ruin and Forsakenness

The remnants of this once blessed kingdom now wrote its long histories:

The remnants of this once blessed kingdom now wrote its long histories:

(i) Remembering its covenantal failures to God over a remarkably long period since the days of Joshua who led them out of the Wilderness into the lands of Canaan;

(ii) Remembering its covenantal judgments for their many failures through numerous occupations as it split in two and became a Northern of 10 tribes and a Southern Kingdom of 2 tribes where the first Jewish kingdom suffered under the brutality of Assyria and the second kingdom under the breakage of the kingdom of Babylon;

(iii) Remembering its final, culminating cycles of repentance-and-restoration from their Babylonian captivity-and-release back into the lands of Israel broken and despised;

(iv) And finally, remembering to rest in the land of their fathers and there to do the hard work of recovering a culture from what they could remember upon the lost shards of time once mishandled with careless disregard. To make sense of a past become even more distant from themselves when cast upon the deep lores of forgotten times now faintly intoned upon the disillusioned lilts of songs and poems by dying tongues remembering fonder memories.

This is the story of the Old Testament before Jesus, before His disciples, before the authorship of the New Testament gospel writers, before the early church's pentecostal beginnings, before the early Church Fathers and their early church councils.

This was the Old Testament without the historical Jesus who was to come. Which looked for a suffering Messiah-Redeemer not understanding what this really meant and sometimes confusing it with God's own suffering people as a nation broken and alone.

This was the Old Testament that spoke of the Holy Spirit as the Spirit of the mighty God without ascribing to the later Trinitarian ideas of Father-Son-and Holy Spirit. Who saw the atoning sacrifices of the Old Covenant but could not make sense of its longer meaning until a toiling early church preacher wrote the NT book of Hebrews to ascribe to Jesus every precept and principal of the Jewish system built upon animal sacrifices and mediating temple.

Of a Jesus who paradoxically became both atonement and atoner. Both altar sacrifice and mediating priest. Both the broken covenant and covenant maker. Both the cleaved bullock halves of Genesis 15 and the Spirit of Him who walked between those halves to renew a covenant that would surely be broken again-and-again-and again in the wayward hearts of a sinful mankind.

Who was the suffering servant of Isaiah (52-53) and the mighty Davidic King who had at last come to reign and take His place among His people. But who offered a kingdom of upside-down proportions. Who sought weakness in place of strength - even in that of his earthly incarnation. Humility in place of grandness. Service in place of cruel reign. Sacrifice in place of survival. It was a King that the world could not appreciate - nor even want - so blinded by its councils and lost sight of the future.

And it was into this gospel era that Jesus, the Son of God, came as provision and provider. Who would re-write the passages and chapters of the Old Testament to once again become illuminescant with an unearthly meaning dared thought or hoped. Who came to re-write the histories of the Old Testament into the furthering chapters of the New Testament where those Jews of the land who had the spiritual vision to see might glimpse their portion of the promise of God made so many long years ago on the eve of their birthright upon the great faith of their Father Abraham. Himself called from the foreign lands of his fathers to leave all he held familiar and true and become a renewing man of faith and vision. And in a sense, a stranger to himself and his past when captured by God's vision for his future.

This is the story of the Old Testament. And the next chapter to its dusty pages scripted onto the heart of Jesus our Savior who would birth the many worlds of the church to come as it struggles even now to lay claim to a belief becoming more distant with every passing era of this new millennium.

A God who surely loves us and has become surety for us through His Son. A God who calls to a people not His own to become a people of His tabernacles. To there reside and no longer take up residence in any other alien lands. To find rest for the weary soul and an everlasting peace that will ever abide upon the faithfulness of His decrees and charters and eternal will. Amen.

A God who surely loves us and has become surety for us through His Son. A God who calls to a people not His own to become a people of His tabernacles. To there reside and no longer take up residence in any other alien lands. To find rest for the weary soul and an everlasting peace that will ever abide upon the faithfulness of His decrees and charters and eternal will. Amen.

R.E. Slater

May 18, 2015

* * * * * * * * * * *

Jesus and the Old Testament

http://www.jrdkirk.com/2015/05/15/jesus-and-the-old-testament/

by J.R. Daniel Kirk

May 15, 2015

My colleague John Goldingay has a new book out. Its provocative title: Do We Need the New Testament? Letting the Old Testament Speak for Itself.

The provocation doesn’t stop with the front cover, as the last chapter is entitled, “Theological Interpretation: Don’t Be Christ-Centered, Don’t Be Trinitarian, Don’t Be Constrained by the Rule of Faith”.

As someone growing my love for baseball, I want to say with all seriousness that batting .667 makes you one of the all time greats! Here’s my two out of three:

- Don’t be Constrained by the Rule of Faith. Agreed.

- Don’t be Trinitarian (in your interpretation!). Agreed.

- Don’t be Christ centered? Not so fast!

But before I lay those out, I want to voice my partial agreement even with the idea that we should not read the OT Christologically. I agree with the claim up to this point: we should always allow the OT to say what it has to say, listen to what it has to say, as an expression of its own historical context as a first reading of the text.

In my forthcoming book on Jesus, I have 50,000 words invested in the notion that what pre-New Testament material says about God, humans, and how they relate is of its own importance, and absolutely essential as well for reading the NT aright.

So I half agree with my colleague. We need to first let the OT speak with its own voice. His batting average is now up to .833!

But we cannot stop there. We have to continue to a Christological reading. Here’s why.

1. The New Testament says that scripture is about Jesus

In the famous “all scripture is God-breathed” passage in 2 Tim 3, where we learn that all scripture–which would have meant our Old Testament–is profitable for teaching, etc., we often overlook something.

Before saying that scripture is profitable, Paul tells us what the outcome of such profitable reading is:

"Since childhood you have known the scriptures which are able to give you the wisdom that leads to salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus."

Scripture has a goal, an end, an outcome: faith in Christ.

This parallels what Paul says in Rom 10:4, when he claims that Christ is the end or goal (telos) of the Law.

It is recapitulated in Jesus’s words in John 5: “You search the scriptures because you think that in these you have life–yet it is these that testify about me!”

If we do not read OT scripture as pointing to something beyond itself, if we do not read it as part of a story that has an end in Christ, we are not reading it in keeping with the NT guidelines.

2. If we don’t read the Old Testament Christologically then Christianity is not true

I know that this is a strong statement. But I’ll stand by it. (At least until one of you talks me out of it in the comments!)

The story of Jesus can only be the story of God’s salvation if it is the answer to God’s promise to save God’s people and restore the cosmos. But a “straight” reading of the text from front to back does not in itself paint for us the picture of the Jesus about whose life we read on the pages of the NT. It does not adequately prepare us for salvation through God’s offering of God’s own Son.

Jesus claims at the end of Luke, for instance, that the whole OT (Law, Prophets, Psalms) speaks to a suffering Christ who thereafter enters his glory. We find out what this looks like, exegetically speaking, in the sermons in Acts.

How does the OT speak of the Christ to come? Only when we return to those scriptures to read them with new understanding after we already know that Christ has been crucified, raised from the dead, and enthroned at God’s right hand.

In other words, if we don’t ever read Psalm 110 as speaking about Jesus’s enthronement in heaven, despite the fact that it was originally about the coronation of Israel’s king, then we have no grounds to claim that what actually happened to Jesus is related in any way to the preceding story.

And if Jesus is not related to the story, then the claim that he fulfills the law and the prophets (Matthew), that he goes just as it is written about him (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), that he is the fulfillment of the promises God made beforehand in the prophets (Paul)–that claim is proved false.

If we do not allow what God actually did to transform our understanding of what God promised to do, we have no answer to the promises of salvation articulated in Genesis-Malachi.

3. If we don’t read the Old Testament Christologically then we have a mess on our hands

I know that this claim is also going to be controversial. But here’s the deal.

Over the past couple of years I have led small groups through studies of both Amos and Isaiah. And those prophets, alongside their beautiful visions of the future, are also a troubling mess.

The heights of proclamation about the mercy and justice of God are interwoven with gruesome vengeance–God meting out on the nations the very sorts of violence for which they themselves are allegedly being punished.

We have to be able to return to passages that look for God to give destroy Egypt as the ransom for God’s people, and say no. No, God chose a different path. God gave God’s son instead.

We have to be able to return to passages that look for God to subjugate the nations as vinedressers and shepherds and say no. No, God chose to bring in the Gentiles on equal footing, bearing the divine image as co-heirs with Christ as much as Israel.

The cross does not make every mess go away–and it is, in many ways, its own mess to wrestle with.

But Jesus does show us what the ultimate revelation of God looks like. It is the God who confronts the enemy–by sending the Son to die on their behalf.

This is what permits us, better, demands of us, that we not allow the depictions of the violence of vengeance to stand. (And, yes, the Jesus story might demand of us that we reread portions of the NT for the same reasons.)

So yes, bracket the Trinity and the Rule of Faith while you read. But don’t leave Christ to the side.

Our faith depends on it.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments

Donald Juels, Messianic Exegesis, 1998. Christological Interpretation of the Old Testament in Early Christianity.

Donald Juels, Messianic Exegesis, 1998. Christological Interpretation of the Old Testament in Early Christianity.

Anon - "Dr Goldingay's approach is helpful in one aspect. It helps us appreciate the fact that no one was thinking in terms of Messianism the way Christians did because they looked at who, and what, Jesus was-and-did and this changed the game. Basically if one reads Donald Juel's Messianic Exegesis he says it all. Juels book is quickly forgotten in these discussions.

Anon - "I have read that Jewish sages figured out that there was a suffering servant Messiah they called Messiah ben Joseph and a conquering king Messiah they called Messiah ben David. What they could not figure out is whether the relevant texts were discussing two Messiahs or just one and there was debate. The puzzle was they did not see how a Messiah that would suffer and die could also reign as king."

Book Review - Messianic Exegesis by Donal Juels

Anon - "Juel's work is one of those books that I wish had been assigned a long time ago. The basic premise of the book is to show that the early Christians were convinced that Jesus was the promised Messiah (meaning "king"), and then undertook the task of reflecting on the good news of his death and ressurection in light of the Scriptures. What came first was NOT apologetic argument but scriptural reflection whose goal was to understand the gospel.

Basically the early Christians take key words from well known Messianic passages already established, and use other passages NOT considered Messianic, and apply them to what they saw happened with Jesus in his unexpected death and resurrection.

This should be required reading for all who study the Bible. I believe this mainly because after being involved in Biblical Studies for a while and digesting all kinds of discussions, I feel that the way things are presented in this book should be the standard for understanding the relationship between the Tanakh and what is referred to as the New Testament.

It is the ultimate way of honoring Christ. The Messiah becomes the one who reinterprets everything that came before. The written word is in submission to the Living Word. SO when the unexpected happens we re-imagine everything in light of [Him who is] the Truth.

This means that one needs to believe first that the death and resurrection of Jesus really happened, and also beleive that the result of this was vindication of His self declaration of being Messiah. When the Chief Priest asked if he was Messiah, Jesus said, "I am".

The other thing that one needs to believe in is that God is fully consistent. So that when something happens later in history after Jesus' resurrection and ascension that is significant, it should always be compared to the death and resurrection and seen as inferior to it. [sic, Christ as the Mid-Point of Salvific History" - r.e. slater]

The other thing that one needs to believe in is that God is fully consistent. So that when something happens later in history after Jesus' resurrection and ascension that is significant, it should always be compared to the death and resurrection and seen as inferior to it. [sic, Christ as the Mid-Point of Salvific History" - r.e. slater]

Colossians 1:15-18 15 - "And He is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation. 16 For by Him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities-- all things have been created by Him and for Him. 17 And He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together. 18 He is also head of the body, the church; and He is the beginning, the first-born from the dead; so that He Himself might come to have first place in everything."