Dr. Noll is a historian and professor of Christian thought at Wheaton College in Illinois, a leading evangelical liberal arts institution. He also is the author of America's God, a history of American Protestant Christianity. In this interview, he offers a summary of American evangelical history beginning with a definition of the word "evangelical." He talks about why evangelicals became more politically engaged in the 1960s and 1970s and how its leadership changed over the following decades: "They have more friends in power [now]. They're more experienced and working for different issues. They have become political, as well as religious, in their public activity." Noll also talks about the many layers of differences between the African-American evangelical community and the white evangelical community and he defines the type of evangelical George W. Bush represents. This interview was conducted on Dec. 10, 2003.

Dr. Noll is a historian and professor of Christian thought at Wheaton College in Illinois, a leading evangelical liberal arts institution. He also is the author of America's God, a history of American Protestant Christianity. In this interview, he offers a summary of American evangelical history beginning with a definition of the word "evangelical." He talks about why evangelicals became more politically engaged in the 1960s and 1970s and how its leadership changed over the following decades: "They have more friends in power [now]. They're more experienced and working for different issues. They have become political, as well as religious, in their public activity." Noll also talks about the many layers of differences between the African-American evangelical community and the white evangelical community and he defines the type of evangelical George W. Bush represents. This interview was conducted on Dec. 10, 2003.

How would you define the word "evangelical?"

"Evangelical" designates both a trait of churches, religious practices, networks. It designates a certain series of convictions or actions, practices. The beginning of the modern movement and its American phase is in the mid-18th century, with revivals in the British Isles, North America, the West Indies. Jonathan Edwards, John and Charles Wesley, and George Whitefield are key beginning figures. From those movements have descended a wide array of religious organizations, churches and voluntary groups, and they are the evangelical movement.

But there are also a series of characteristics and designations, beliefs and practices -- of which four have been designated by the British historian, David Bebbington, and provide a very good summary designation of what evangelicals do and believe.

His four characteristics are: (1) a very strong belief in the Bible as the primary religious authority; (2) a commitment to the practice of conversion, so that people need to be changed in a Christian direction as a basis for participation in the life of God; (3) activism, especially a willingness to tell other people about the message of salvation in Jesus Christ; (4) a special assessment of the work of Christ on the cross - [that the] death and resurrection of Christ is the heart of the Christian faith.

These four characteristics do work quite well to designate a broad family of religious interest.

Are there certain denominations that fit underneath this, and others that don't?

Evangelical is a slippery word, because it can be used to designate certain religious groups or denominations. But then it also can be used to transcend denomination. So there would be in the United States evangelical Presbyterians, evangelical Episcopalians, evangelical Lutherans.

But there would also be lots of individual congregations that would be evangelical in some general sense. The Southern Baptist Convention, which is the largest Protestant denomination in the United States, would certainly be evangelical. Although because it is its own thing, and it's so big in the southeastern part of the country and large in other parts of the country, many Southern Baptists do not use the word "evangelical" for themselves, though everyone outside knows that they are.

So the word is plastic. The concept is not precise. Evangelical movements have been identified and identifiable. Evangelicals recognize each other, often by how they sing hymns, and what hymns. But it's not a hard and fast designation.

The word "evangelical" does designate a limited range of beliefs and practices. But it's not a word like Baptist or Presbyterian or Roman Catholic, because its designation is for a certain characteristic way of being religious.

Evangelicals tend to operate against tradition, but there are some traditional evangelicals. Evangelicals historically have been opposed to the Roman Catholic Church. Today, there are Roman Catholics who call themselves evangelicals. So the word is flexible, but it does have a core of meanings that have been associated with it.

The evangelicals that we talked to, they're mostly Republican. But this hasn't always been the case, right?

Historically, from shortly after the Civil War into the 1950s and 1960s, most people who were evangelicals shared the political viewpoints of their region. So it's probably the case that the individuals that sociologists, historians, would now call evangelicals were predominantly Democratic into the 1960s, because so many of them were in the South, and so much of the South was Democratic.

In the last 40 years, that situation has changed, because of political alterations that have taken place in the South. The movement of whites in general to the Republican Party in the South has included the movement also of white evangelicals to the Republican Party.

Northern evangelicals always tended to be more Republican than Democratic, but that is because they were part of the Northern white Protestant establishment. That was just as true for mainline Presbyterians and Lutherans as it was for Baptists and members of independent congregations.

Then there are also the changes in terms of evangelicals becoming more engaged politically. For example, I am thinking of the 1970s, when Roe v. Wade was passed....

Important things happened from the 1960s and 1970s. One was a process by which evangelicals became more actively involved in political life in general. For that to happen, it took national Supreme Court decisions having to do, I think, primarily with school prayer and abortion, that represented an affront to many evangelicals, North and South, represented what was seen by many as an illegitimate extension of government power.

So there was a process by which formerly quiet evangelicals became more active politically. The Republican campaign of Pat Robertson in 1988 was not particularly successful politically. But it did succeed in energizing particularly the Pentecostal and Charismatic parts of the evangelical world that were characterized by a kind of pietistic indifference to political life.

But along also with increased involvement was a change in partisanship. The political scientist whom you've talked to can explain that in great detail.

But what seems to have taken place is that, as the Republican Party came to be seen as the party with a moral agenda, it attracted middle class, lower-middle class white Southerners, and added those evangelicals to the Northern evangelicals who had been primarily Republican all along.

So what you are saying is that, along the way, there were a couple of decisions by the Supreme Court that ignited evangelicals to become politically active, and in doing so, they started to relate more to the Republican Party -- a party which also was taking on a more moral platform?

Yes. Two things happened from the 1960s. One was a fairly widespread evangelical resentment at the extension of federal power via the courts, particularly with the school prayer decision and the Roe v. Wade abortion decision.

Resentment or nervousness about extending government power goes back to the 1930s and 1940s. But these particular cases in the 1960s and 1970s sparked political mobilization of a sort that had not been present before.

Along with a more general interest and involvement in political life came then this shift of partisanship. Middle-class and lower-middle class, largely white evangelicals, often Southern, who had been instinctively Democratic, began to be instinctively Republican, as the Republican Party … came to be seen as the party of family values or traditional values.

Tell me what "traditional family values" means to an evangelical.

Most white evangelicals, North and South, would probably see family values as related to influence in the local schools, as preference given to traditional families, one man, one wife married. Traditional values would include protection for children. Traditional values would include protection for life.

I think there probably are strong family elements in most evangelicals' opposition, for example, to abortion on demand.

Over the past 30-40 years, in what ways has this leadership changed or evolved?

Evangelicals have no given leadership. There is no pope in the evangelical world. But over time, different individuals do come to the fore as recognized leaders -- sometimes recognized within evangelical groups, sometimes recognized by the outside.

One of the really important developments after World War II was that Billy Graham and his associates came to be recognized leaders inside the evangelical world, and as spokespeople for evangelicals on the outside.

Billy Graham and his circle were always interested in politics, but in a low-key way that was pretty quiet, pretty much oriented toward behind-the-scenes influence. That generation of evangelical leaders eventually gave way in the 1970s and 1980s to a more assertive, a more aggressive, a more abrasive leadership. That was energized by the moral struggles precipitated by the Supreme Court decisions, but by other matters as well.

So Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and eventually Dr. James Dobson were not so much concerned about keeping together the coalitions that the Graham people had worked on, but were concerned about standing up for what they thought was important in American life and what was threatened.

A good question could now be raised whether there might be a shift of generations taking place again, with leaders like Bill Hybels and other significant local ministers of the mega-churches often, but of other significant churches who do have a more peaceful demeanor, but who may be just as adept politically as some of those from earlier generations.

Would you then separate the fundamentalists from the evangelicals in the leadership of the movement over recent decades?

Well, sometimes people … want to make a strong distinction between the word "evangelical" and the word "fundamentalist." I myself do not do that, because I think usually the word "fundamentalist" is used of people you don't particularly like. There aren't too many people who call themselves fundamentalists, and so the word can be abused.

I, for one, do not actually think it's helpful to call the major evangelical political leaders of the 1970s, 1980s, fundamentalists, as opposed to evangelicals. I do think, however, they were in earlier stages of political mobilization. Leaders that have come to the fore in the 1990s and on into the 21st century -- and

Richard Land of the Southern Baptists would be a good example of these -- have many of the same beliefs and practice, many of the same things as the generation in the 1980s and 1990s, but have a greater political expertise.

They have more friends in power. They're more experienced, and working for different issues. They have become political as well as religious in their public activity.

When we look at polling numbers, evangelicals are mostly white. Why is that the case?

One of the most important features of American religious life is the political difference between blacks and whites who otherwise share a tremendous amount in their religious beliefs and religious practices.

When pollsters talk about evangelicals, they usually mean white evangelicals, and white evangelicals vote now overwhelmingly for the Republican Party. It would be legitimate, from a religious point of view, to regard huge sections of the African-American churches in the United States as evangelicals. They believe in the Bible. They believe in conversion. They are supernaturalists. On moral issues, they oppose abortion. They believe that marriage should be restricted to one man and one wife.

But on political issues, blacks, and especially African-Americans who go to church, vote for the Democratic Party. The reason for this feature of American public life -- and it's a very important one -- the reason is rooted in history, culture and the social divisions that have divided whites and blacks in United States history.

From the period before the American Civil War, evangelical religion became very strong in the African-American community. But African-Americans were at first enslaved, and then segregated, discriminated against, by a number of white communities, including the religious, the Protestant community.

So over the last 150 years, there's grown up an almost separate religious culture for African-Americans, divided from the religious culture of white Americans. There are some exceptions. But these two cultures, though they often share similar beliefs and practices religiously, they have been socialized into very different political behavior.

We talked to four students here at Wheaton. There were three white students from the Midwest. There was a fourth black student, also from the Midwest, and she's one of 35 or so black students on campus. I asked them, "What are the issues that you would vote on?" The first three kids said the moral issues. Abortion [and] gay marriage was very important to them, and the war, supporting the troops. They all said that. The black student said education, social welfare and then the war, but didn't list the moral issues. When I asked who would vote for Bush, the first three white kids said George Bush. And she said, "I just don't know yet." Does it surprise you?

Not in the least. Not in the least. Black churchgoers and white churchgoers who would share a common set of evangelical beliefs almost predictably are going to come down on different sides of the modern political debate.

African-American churches, and especially urban churches in the main cities of the United States, are concerned about issues bearing in on those communities. Those issues have to do with support for public education. They have to do with the provision of welfare for stressed families. They have to do with the provision of work and government policies that support the ability to make a living.

White evangelicals are -- not exclusively -- but they are comfortable in the suburbs, and in the small towns and rural areas of the United States. Those two environments historically and contemporaneously have posed different ranges of social issues, and have put different social issues in the forefront of church concern, as well.

So we have in the United States now a situation where religion is the second-strongest indicator of public partisan behavior. But race remains the number one indicator.

That's really interesting, isn't it?

...If you can somehow point out that huge numbers in the black churches are evangelical in a religious definition, that will actually be a step ahead, a step forward.

I keep hearing from black Protestants that, "Hey, we're evangelical, too. But I'm not going to call myself evangelical."

That's exactly right One of the interesting divisions between black America and white America is in the use of the term "evangelical." White churches and white church people who have the traditional evangelical beliefs in practice are much more likely to call themselves evangelicals than African-Americans who might share the same beliefs in doctrine and share the same attitudes toward moral practices.

Black evangelicals, and people whom historians might call black evangelicals, are much more likely themselves to use terms like "Bible believers," "spirit-filled," "true Christians," "folk on fire for the Lord" and not use the word "evangelical," because in American public discourse that is a word usually used by and about white folk. There's actually a complication with Hispanics too, but you don't want to get into that.

Why is it that, right now, mainline Protestant churches are going along at a sort of steady pace and even declining, and evangelical churches are definitely seeing an increase? What's going on right now?

The churches that are known as evangelical today are descended from the mainline Protestant churches of the 19th century. When a distinction is made between evangelical and mainline churches, it's not a hard and fast distinction. There are many, many evangelical mainline Protestants.

But the mainline churches are traditional. They are less entrepreneurial, less flexible in relationship to cultural [issues], and have, for reasons of belief and practice and organization, not fared nearly as well in the postwar world as have more self-consciously, self-identified evangelical churches.

Would you consider President Bush an evangelical?

George Bush is evangelical, but evangelical of a particular type. His church in Midland, Texas, as I understand it, shares some characteristics of the mega-churches. It is, however, a Methodist church, but it's a Southern Methodist church. It's a largely white church. It's a church that does not stress doctrine, but stresses community and fellowship and therapy.

So, yes, George Bush is an evangelical. But he's one kind of evangelical in a mosaic that includes many, many other kinds of evangelical Christians.

When you say "of a particular type," what do you mean?

George Bush is an evangelical of a certain type. There are evangelicals in the mainline churches, of which he would be one. There are churches that have a mega-church style, of which his would be one. There are evangelical groups that emphasize the kind of therapeutic rescue that his group of supporters in Midland provided for him after he turned from alcoholism.

1. The Hole in Our Gospel by president of World Vision Richard Stearns is a fantastic introduction to the centrality of justice to the gospel message. Packed with biblical references and personal testimonies, it’s the kind of book you can safely introduce as a book study option at your church if your group includes participants with a variety of political and theological viewpoints. Stearns issues a moving call to action that challenges Christians to look beyond the walls of their churches and work together to demonstrate God’s love for the world by acting justly, loving mercy, and walking humbly with God.

1. The Hole in Our Gospel by president of World Vision Richard Stearns is a fantastic introduction to the centrality of justice to the gospel message. Packed with biblical references and personal testimonies, it’s the kind of book you can safely introduce as a book study option at your church if your group includes participants with a variety of political and theological viewpoints. Stearns issues a moving call to action that challenges Christians to look beyond the walls of their churches and work together to demonstrate God’s love for the world by acting justly, loving mercy, and walking humbly with God.  2. In Half the Sky, Pulitzer Prize-winning duo Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn explain how investing in the health and autonomy of women worldwide will lift millions out of poverty. According to the authors, more girls have been killed in the last fifty years, precisely because they were girls, than men were killed in all the wars of the twentieth century. Focusing on sex trafficking, gender-based violence, and maternal mortality, the authors masterfully incorporate colorful stories of real women who have both suffered from oppression and triumphed over it in order to make the case that “women aren’t the problem but the solution. ” This is by far the most well-written book about poverty and injustice that I’ve read. What I love about it is that it really gives the reader a sense of being “on the ground,” where there are no easy answers and no simple categories of victim and rescuer. (In light of recent conversations here on the blog, I found it interesting that the authors are very much in favor of Westerners taking short-term trips to impoverished areas of the world.)

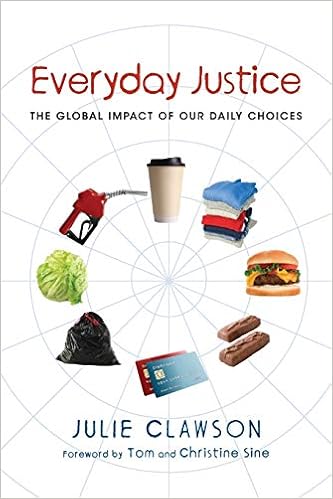

2. In Half the Sky, Pulitzer Prize-winning duo Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn explain how investing in the health and autonomy of women worldwide will lift millions out of poverty. According to the authors, more girls have been killed in the last fifty years, precisely because they were girls, than men were killed in all the wars of the twentieth century. Focusing on sex trafficking, gender-based violence, and maternal mortality, the authors masterfully incorporate colorful stories of real women who have both suffered from oppression and triumphed over it in order to make the case that “women aren’t the problem but the solution. ” This is by far the most well-written book about poverty and injustice that I’ve read. What I love about it is that it really gives the reader a sense of being “on the ground,” where there are no easy answers and no simple categories of victim and rescuer. (In light of recent conversations here on the blog, I found it interesting that the authors are very much in favor of Westerners taking short-term trips to impoverished areas of the world.)  3. If you are looking for a super-practical guide to living more justly, I highly recommend Everyday Justice by Julie Clawson. I used this book to plan most of my activities this month, and it is has proven to be an invaluable resource for making better decisions as a consumer. With seven easy-to-read chapters on coffee, chocolate, cars, food, clothes, waste, and debt, Julie shows how our everyday decisions can affect people around the world. Best of all, each chapter concludes with lists of additional resources that provide readers with the books, documentaries, and Web sites they need to learn more and to put their resolutions into action. You don’t have to take all of Julie’s suggestions of course, but incorporating just a few can make a big difference.

3. If you are looking for a super-practical guide to living more justly, I highly recommend Everyday Justice by Julie Clawson. I used this book to plan most of my activities this month, and it is has proven to be an invaluable resource for making better decisions as a consumer. With seven easy-to-read chapters on coffee, chocolate, cars, food, clothes, waste, and debt, Julie shows how our everyday decisions can affect people around the world. Best of all, each chapter concludes with lists of additional resources that provide readers with the books, documentaries, and Web sites they need to learn more and to put their resolutions into action. You don’t have to take all of Julie’s suggestions of course, but incorporating just a few can make a big difference.  4. Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger by Ronald Sider was the first book to really inspire me to rethink the way that I live in relation to my global neighbors. First published back in 1977, the book has been thoroughly revised and updated. (I read the 2005 version.) Like The Hole in Our Gospel, it provides a comprehensive biblical case for caring about justice, but with an emphasis on the contrast between Western materialism and worldwide poverty. Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger was named one of the Top 100 Religious Books of the Century by Christianity Today, and it is well-deserving of that honor.

4. Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger by Ronald Sider was the first book to really inspire me to rethink the way that I live in relation to my global neighbors. First published back in 1977, the book has been thoroughly revised and updated. (I read the 2005 version.) Like The Hole in Our Gospel, it provides a comprehensive biblical case for caring about justice, but with an emphasis on the contrast between Western materialism and worldwide poverty. Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger was named one of the Top 100 Religious Books of the Century by Christianity Today, and it is well-deserving of that honor.  5. Last night after dinner, I finally picked up Half the Church by Carolyn Custis James and, believe it or not, I’d finished it by 1:00 a.m.! I loved this book! In it, James argues that the Church’s emphasis on marriage and motherhood is not far-reaching enough to encompass every woman’s whole life within a multicultural, rapidly changing world. In order to take on the sort of injustices we encounter in Half the Sky, Christian women must be freed to lead and to capitalize on God’s positive, life-affirming vision for them. I was absolutely thrilled to see James, an evangelical, interpret passages like Genesis 2 and Proverbs 31 in ways that I believe are much more faithful to the original meaning of the text than are typically presented at Christian women's conferences. James issues a stirring call for the Church to move beyond stifling arguments over gender roles and embrace a holistic understanding of God’s calling for both men and women. I wrote “amen” in the margins more times than I care to admit.

5. Last night after dinner, I finally picked up Half the Church by Carolyn Custis James and, believe it or not, I’d finished it by 1:00 a.m.! I loved this book! In it, James argues that the Church’s emphasis on marriage and motherhood is not far-reaching enough to encompass every woman’s whole life within a multicultural, rapidly changing world. In order to take on the sort of injustices we encounter in Half the Sky, Christian women must be freed to lead and to capitalize on God’s positive, life-affirming vision for them. I was absolutely thrilled to see James, an evangelical, interpret passages like Genesis 2 and Proverbs 31 in ways that I believe are much more faithful to the original meaning of the text than are typically presented at Christian women's conferences. James issues a stirring call for the Church to move beyond stifling arguments over gender roles and embrace a holistic understanding of God’s calling for both men and women. I wrote “amen” in the margins more times than I care to admit.

My observation is that often lack of charity is a function of immaturity. Thus very conservative speakers who are mature often have followers who are less mature and so exhibit the signs of fundamentalism absent from their doyens.

Since fundamentalism in Roger’s sense is not primarily a theological category as a personality or moral category, what we need is a kind of checklist to see if one is drifting towards it. One cannot tell simply by looking at one’s theology. A follower of Bultmann could be just as much a fundamentalist as a follower of John Piper.

One question we should ask ourselves is whether we can learn from those we disagree with. Bonhoeffer was someone that evangelicals regarded with distaste in the 1930s as being a liberal, or at least neo-orthodox. Time and martyrdom have lent a lustre to his reputation even among many evangelicals. But can we learn today from those outside our camp, successors if you like of Bonhoeffer?

Another question might be is there a positive and edifying priority in our teaching. Sometimes one can be far more concerned to condemn error in others than to affirm and expound truth, whether from our own tradition or from another’s. This is a particular tendency among the followers of the “great men.” It is so much easier to master the criticism of others than the exposition of our own understanding.

Roger rightly raises the issue of power plays. When we use power to enforce our views then I think we are up against something that if not fundamentalism is at least very distasteful.

But all this means that one issue that needs to be teased out is how we go about refuting error (as we see it). We need to have ways in which we discuss, debate and reject various views and even campaign against them. Roger’s blog is an attempt to do so. But there is a need to work out how we can do this responsibly. Roger may have mastered the art of doing it himself but the elements of such an art need to be brought to light for others to follow.

Roger says

Thank you for that very interesting comment; it is one with which I substantially agree. I would say, however, that I only use “fundamentalist” and “neo-fundamentalist” for those on the right of the theological spectrum. It seems odd, to say the least, to apply these to those on the left, as they are tied to the original fundamentalist movement and especially its post-1925 manifestations in the U.S. and perhaps Britain. The great leaders of the fundamentalist movement throughout the 1930s and 1940s and into the 1950s and 1960s tended to be men who would sometimes sacrifice integrity or civility in order to make their points and keep their followers in line. We need a parallel word for liberal leaders who do the same; I’m not sure what it should be. One principle I try to follow to avoid that tendency is to always be sure I understand before saying I disagree and to measure the volume and intensity of my disagreement to my level of certainty about the disagreement. I think fundamentalists and neo-fundamentalists tend to jump the gun, so to speak, when reacting to perceived liberal or liberalizing moves made by fellow evangelicals. And they often allow the volume and intensity of their disagreement to grow way out of proportion to the importance of the matter.